When there are free bagels and coffee going untouched at a New York City event, something serious is at hand.

This was the scene Tuesday where nearly 7,000 doctors, nurses, and health care workers in jeans, scrubs, and nursing shoes sat listening to the panel members of an emergency meeting on Ebola education.

“This is the first time we’ve asked you to clean your gloves with alcohol,” Dr. Arjun Srinivasan, an associate director at the National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, bellowed in front of a large projection screen near the stage. “This is vital.” Some heads nodded in recognition of this, others look startled.

“How do you protect from infection?” Srinivasan solicits the crowd. “Wash your hands,” they drone out in eerie unison.

“Yes. Clean hands save lives. It’s true every day,” says Srinivasan, who is currently leading the Response Team of the Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The crowd, motionless until now, erupts in applause.

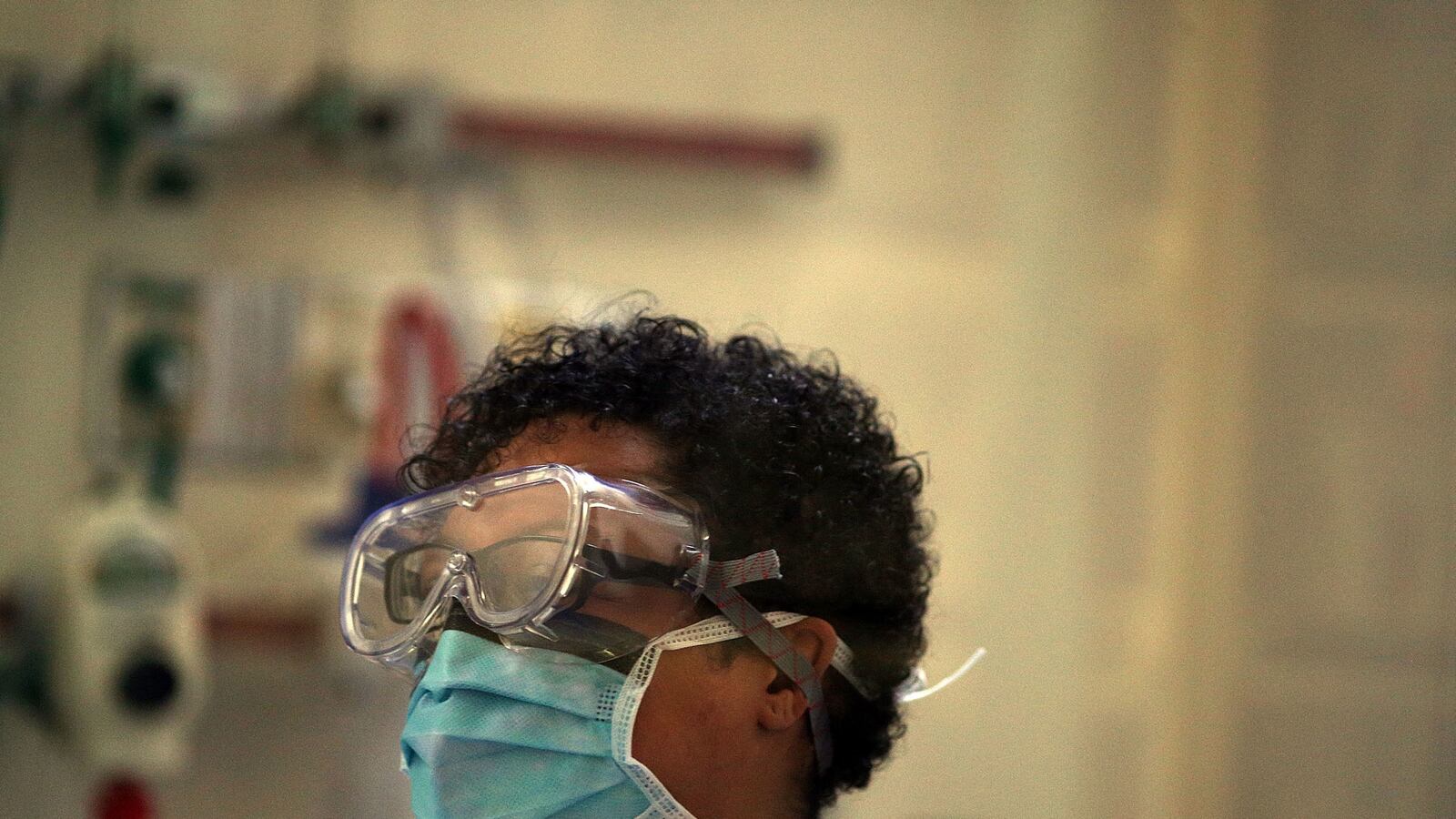

As important events illustrating the measured calm with which health care workers are preparing for this epidemic go, Tuesday’s meeting was pitch perfect. After additional comments from leaders in New York’s health care system, two more CDC members took the stage to illustrate, in painstakingly meticulous detail, how to remove the personal protective gear without exposing it to themselves. Cell phones and iPads aimed upwards towards the stage, and at half a dozen projectors playing it for those further back, the healthcare workers captured what to do should the epidemic arrive at their own facility. An appropriate level of concern was evident everywhere; panic was nowhere to be found.

Given that two nurses are among the three cases of Ebola in the U.S., a palpable fear in the room would not have been surprising. The infection and, ultimately, tragic death of America’s first Ebola patient Thomas Eric Duncan led to the monitoring of 70 health care workers in Dallas. More than five dozen workers at risk from treating one single patient aren’t exactly great odds.

It is these men and women who are the most likely to contract the disease, should it once again find itself on American shores. This isn’t complicated—it’s science. Ebola causes the body to excrete fluids that are teeming with the virus. Nurses are the first line of defense. They know this; and ironically, judging by this meeting, are at peace with it.

Suzette Sterling, a nursing assistant at an Upper East Side nursing home says she was upset upon hearing the news that two nurses in Texas were infected, but not afraid. A desire for more information motivated the Trinidad and Tobago native to come. “I want to learn how to protect myself and my patients,” she says, clutching a blue bag with bright white letters that say “Protect Against Ebola.” Sterling came as the representative of her facility, which could not handle sending more than one person. She plans to head back to inform her team. “We want to be prepared.”

Maurice de Palo, a pharmacist at Montefiore Medical Center in the Bronx. Like many of the other attendees, he’s also a delegate for the Healthcare Workers East union. “It’s smart to be here,” he says. “It’s very informative to be here to learn and be knowledgeable about this subject.” But unlike many of the others I spoke with, de Palo says he has experienced some fear in the medical community. “The fears in epidemic proportion and they need to be calmed down,” he says. “The fear is real because people don’t understand the virus, just like the AIDS epidemic. They don’t want to be near people they’re afraid to associate,” he says. “See what happened to the airline industry? People are afraid to be on the same plane.”

Caroline Trimm, a nurse counselor at Greenwich House in the SoHo district of Manhattan, seems to have the opposite view. “The new changes are great,” she says of the CDC’s revisions to protocol for healthcare workers that includes zero exposure to skin. “The gloves washing with the alcohol, that makes sense to me.”

Greenwich House, where Trimm works, is a nonprofit organization that provides, among many other things, medical care to the underprivileged. Many of these are homeless people. “We have patients that come in off of the street, so we never know where they’re coming from and who they may have been exposed to,” she says. “It makes you more cautious and more aware of asking that question of where they were and if they have traveled or not.”

Despite reports of soaring calls to the CDC from Americans each day concerned about Ebola, Trimm says she’s seen few patients exhibiting the same fear. When I ask if her fellow nurses are afraid she shakes her head. “Not really, ‘cause it’s New York,” she says. “We learn how to roll with the punches.”

The sentiment shared across platforms at the meeting was anger at the press for sensationalizing the problem. “We’re not worried, but the media is,” says one healthcare worker from Manhattan, who asked to remain anonymous. “We understand that the risk is low but they don’t. 24/hour coverage is too much.”

Tatyana Akhmatova, a 65-year-old native of the Kyrgyz Republic who now works as a nurse the Bronx, agrees. “You hear something from radio, something from TV, something from computer. But you don’t know definitely what is it,” she says. “For that I am coming; I need full information about it. Now I will know. I will be ready.”