Two male journalists, one conservative and one contrarian, were to debate abortion at Oxford University earlier this week. The event was sponsored by a student pro-life group and had all the ingredients to provoke an impassioned campus protest: two men, both right-leaning, debating an issue not often debated in England. And what do they know about terminating a pregnancy anyway?

It’s a fair question, one that could have been put to either journalist in a spirited debate (the very thing we expect to happen within the walls of a university). Or better yet, instead of wasting an evening listening to two men do battle over who controls a woman’s uterus, the aggrieved, pro-choice student could have simply skipped the event altogether.

But for those who were offended that someone with a penis might discuss abortion at all, opting to skip the event wasn’t enough. After the student union Women’s Campaign (WomCam) urged the Oxford Students of Life to cancel the event and demanded an apology for attempting to stage the debate, the university called it off entirely, a move critics slammed as a grave restriction of free speech.

After the event was canceled, in a spasm of alarming anti-intellectualism and illiberalism, Niamh McIntyre, a female student at Oxford, wrote in The Independent, “The idea that in a free society absolutely everything should be open to debate has a detrimental effect on marginalized groups.”

She insisted that she “did not stifle free speech” in calling for the event’s cancellation. (Only school administrators have the power to enact censorship, after all.) “As a student, I asserted that [the debate] would make me feel threatened in my own university; as a woman, I objected to men telling me what I should be allowed to do with my own body.”

It’s safe to say that, in the United Kingdom especially (where only seven percent want a total ban on abortion), most women object to men telling them how the law should govern their bodies, particularly when it comes to reproductive rights. But that doesn’t mean men, whether or not their ideas are “offensive” or ill-informed, should be denied the right to argue their case.

According to McIntyre, “Debating abortion as if it’s a topic to be mulled over and hypothesized on ignores the fact that this is not an abstract, academic issue.” But her real argument is that only those directly affected by abortion (women) can participate in an ethical debate on the subject. (While we’re at it, are there topics that only men can debate?) And McIntyre’s argument could be made by both sides—or anyone so sure of their position that they no longer believe it a subject to be “mulled over or hypothesized on.”

The Oxford abortion controversy is the latest example of an increasingly common instinct among certain feminists to argue that certain subjects and certain arguments are either off limits or simply not up for debate.

Take feminist writer Jessica Valenti. Responding to a Sunday New York Times column arguing that new affirmative consent laws are too broad and difficult to enforce, Valenti denounced its author, Yale Law School professor Jed Rubenfeld, as a “rape apologist.”

The core of Rubenfeld’s piece—that universities should not be responsible for adjudicating rape charges and that “yes mean yes” policies are deficient—has been cogently argued by legal experts and social scientists, and in turn provoked many cogent counter-arguments.

Sure, Rubenfeld makes some controversial points, like his claim that the “redefinition of consent… encourages people to think of themselves as sexual assault victims when there was no assault.” But controversial or not, nowhere in his piece does he “apologize” for rapists or excuse the crime of sexual assault. To accuse him of doing so is certainly an effective way to end a conversation. After all, what reasonable person would engage in argument with someone who is apologizing for rapists?

Like McIntyre, Valenti argues that “the worst offense is Rubenfeld’s apparent belief that there is a ‘debate’ to be had as if there are two equal sides, both with reasonable and legitimate points.” But worse is Valenti’s suggestion that her views—and those who agree with her—are the only reasonable and legitimate ones.

Predictably, Rubenfeld’s op-ed provoked backlash at Yale too. Some 75 students signed a lengthy letter condemning his “overly narrow view of the purpose of processes that allow survivors to report sexual misconduct and seek support on college campuses.”

The letter gave the impression that Rubenfeld had no support at Yale, but some students have quietly taken his side. “There actually are a large number of students who agree with him but are not at all comfortable coming forward in his defense,” a female law student at Yale who wished to remain anonymous told the Daily Beast. “I think that speaks to a lack of intellectual diversity in the conversation.”

“There is a baseline agreement when it comes to campus rape: the current system is failing these students,” she added. “People who don’t agree on a particular policy to address the campus rape crisis are not rape apologists.”

But lately many feminists seem more focused on setting “acceptable” conditions and standards of debate than on taking political action to combat sexism and sexual assault.

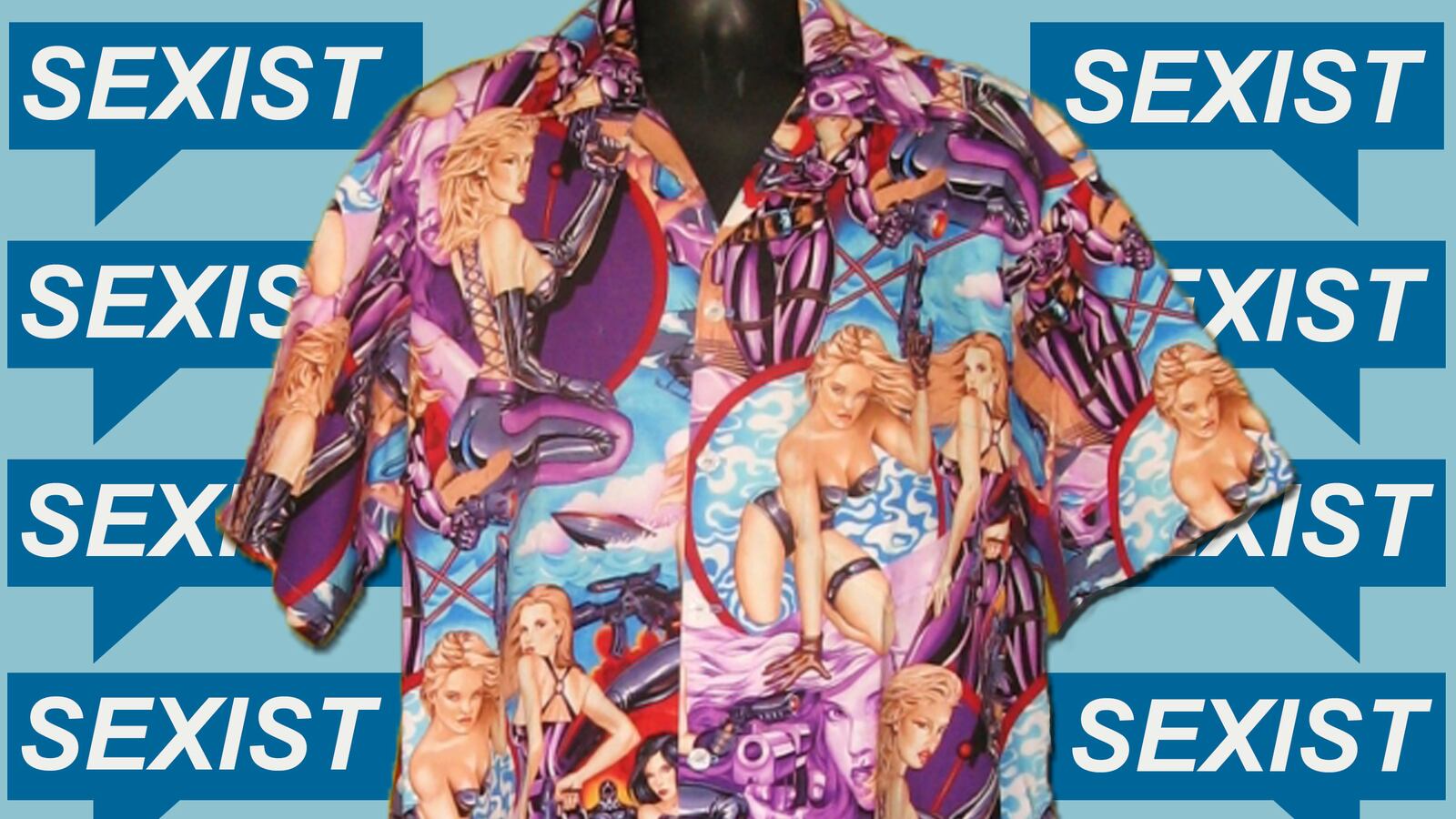

Last week, scientist Matt Taylor’s momentous Rosetta mission achievement of landing a spacecraft on a comet was overshadowed by a garish bowling shirt he wore to a press conference depicting busty, leather-clad anime women straight out of the Heavy Metal comic series. Attacked on Twitter and by outraged columnists for promoting sexism, Taylor issued a tearful public apology.

British comedian Daniel O’Reilly’s tasteless, misogynistic TV series “Dapper Laughs” was axed six days after it went on the air after some 70,000 people signed a petition calling for its cancellation, condemning its “misogynistic views, all under the guise of harmless comedy.” (The nail in the coffin for O’Reilly was a vile rape joke.)

And last week, a petition to remove the word “feminist” from Time’s jokey annual list of words to ban from popular vernacular—along with “bae,” “kale,” and “om nom nom nom,” it is a compendium of overused language—resulted in an apology from the magazine’s managing editor. A description next to the word justified its inclusion on the list: “You have nothing against feminism itself, but when did it become a thing that every celebrity had to state their position on whether this word applies to them, like some politician declaring a party?”

But apparently the article’s irreverent tone was lost on petitioners, who wrote that the inclusion of “feminist” in the anodyne poll “adds to the hateful push against those who fight for equality every day.”

The word was not removed, but Time’s managing editor Nancy Gibbs’ ingratiating apology— “while we meant to invite debate about some ways the word was used this year, that nuance was lost”—was a victory for feminists whose current mission is less about equality than policing the culture for language that offends or threatens their sensibilities. In doing so, they are perpetuating the trope that women are the fairer, more vulnerable sex—the very same one feminists fought for decades to eradicate.

Even celebrated feminist writers and activists have said the movement is in danger of misrepresenting itself and reinforcing old stereotypes.

British feminist Julie Bindel, who co-founded the group Justice For Women and helped change British homicide laws to better protect women in domestic partnerships, recently called out “the emergence of feminist preciousness” in The Guardian, arguing that feminists seem to have reverted and “lost the strength and confidence to effectively challenge institutions.”

“Petitions have taken over politics,” Bindel wrote.

And popular feminist writer Sally Kohn warned in The New Republic of “the risk of feminist overreach,” as well as the risk of women’s voices being stereotyped if “girls, and women, cry sexism too readily and often.”

“The minute feminism becomes hypercritical and humorless, it becomes too easy for the mainstream to dismiss our more valid complaints,” Kohn wrote. “And let’s be honest, it’s kind of refreshing for feminism to be at the cool kids’ table of society at the moment, fraught and confining though it might sometimes be. Does anyone really want to return to the period of sidelined, shrill feminism?”

To sit at the “cool kids’ table of society” is to be in a position of power, backed by the rallying cries of other feminist cool kids. This newly exalted position also comes with responsibility to challenge fellow feminists and engage in debates about everything from reproductive rights to pay equity. And now, more than ever, feminists at the head of that cool table should fight feminism’s increasingly censorious instinct as doggedly as they fight for equality.