Even though I’d been living in Washington, D.C., for most of his time as “Mayor for Life”—suffering with the rest of the citizenry through high taxes, a rising murder rate, and less-than-stellar city services—I didn’t actually speak with Marion S. Barry Jr. until a March day in 2002.

That was when he tried to arrange a date with a young woman not his wife, somehow misdialed, and left a flirtatious voicemail message instead on the home phone of my then-girlfriend. Since I was toiling away at the time as a gossip columnist for The Washington Post, I immediately called him back. “You’re not going to write about this, are you?” Hizzoner asked in a pleading tone—an extremely rare posture for a man who in the past had swaggered with an air of invincibility.

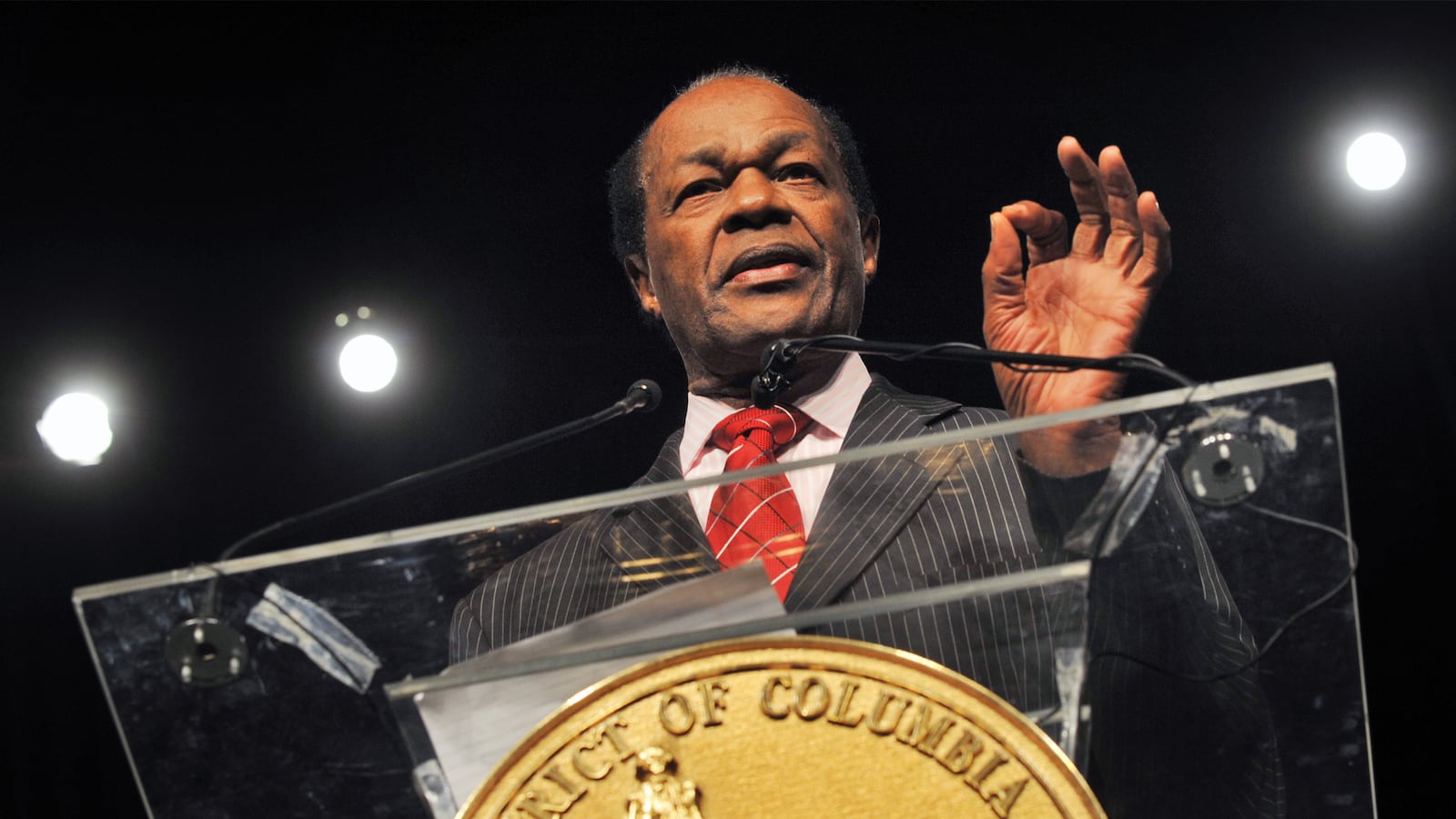

The spectacularly flawed yet charismatically blessed and much-loved career politician—who collapsed and died early Sunday morning, at age 78, outside his house in D.C.’s economically challenged, crime-plagued Ward 8—was between public offices at the time of his misdial, earning his keep as some sort of Washington consultant and wandering in a kind of psychic wilderness, untethered from his sense of self and real purpose in life.

SPEED READ OF MARION BARRY’S MEMOIR

He’d been laying the groundwork for yet another political comeback—a race for City Council. The rascally image of the Old Marion Barry—the womanizing “Night Owl” who’d served six months in the federal pen after an FBI sting in which he was lured to a hotel room by an ex-lover and videotaped sucking on a crack pipe—was wildly contraindicated. “Bitch set me up!” was hardly an inspiring campaign slogan.

So I invited Barry to lunch and—notwithstanding his natural suspicion of reporters, especially white Washington Post reporters—it was an offer he couldn’t refuse.

Barry was a half-hour late to Georgia Brown’s, an upscale Southern-cuisine restaurant favored by Washington’s black establishment. He ordered extravagantly and ate little, taking most of his food away in a trio of doggie bags, and spent much of the meal yakking on his cellphone, including dispensing career advice to his then-22-year-old son Christopher.

Yet, it didn’t strike me as rude; on the contrary, it was a dazzling piece of performance art. And any time Barry managed to tear himself away from his phone and turn his attention to me—slyly subverting my journalistic agenda of finding out what he’d been getting up to lately, and instead drawing me out on my life and job experiences—I found myself unable to resist his personal magnetism, to say nothing of his narrative of personal redemption.

“I identify with the fallen, whoever they may be,” Barry told me years later, in July 2013, during a weekend visit to New York. “Everybody, at some point in life, is gonna get knocked down.”

He added: “I don’t care who you are, how rich you are, how poor you are. A divorce might pull you down. Drugs may pull you down. Kids who are out of control may pull you down. A serious death in your family. What I say to people is, if you fall down, fall down on your back. Then you can look up. If you can look up, you can get up. And if you can get up, you can go up.”

Barry surely experienced more than his share of getting knocked down, some of it self-inflicted: drug and alcohol abuse, prostate cancer, diabetes, a kidney transplant, public humiliation. And he never took responsibility for many of his mistakes—blaming his crack prosecution, at a time when D.C. was reeling from drug-related violence and Barry had been hypocritically preaching to school kids not to indulge, on a white Republican conspiracy to persecute a powerful black man. But he also kept his sense of humor, some of it self-deprecating.

“I’m very quotable,” he told me, regarding his notorious exclamation regarding his betrayal to the FBI by his ex-lover Rasheeda Moore—which for a while was a popular T-shirt slogan. “What I regret is not printing the T-shirts.”

Barry was certainly a manipulative pol—a tax-dollar spendthrift whose cronies had been permitted to gorge themselves on the public during his four terms as mayor (the last of which he won after prison). But he was also a star, and he knew it. A major figure in the civil-rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s, as a founding member of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, the Mississippi-born Barry was never squeamish, and arguably reckless, when it came to exploiting racial divisions for political advantage, doing incalculable damage to the city he claimed to cherish. Yet in person he was a charmer, and seemed to value the folks he came in contact with, whether black or white, for their essential humanity.

Despite everything, I liked the guy.

So a few days after our lunch at Georgia Brown’s, it was disheartening to read that Barry had been accosted by the U.S. Park Police while parked illegally late at night at Washington’s remote Buzzard Point on the Anacostia River; he was sitting in his Jaguar, where trace amounts of weed and cocaine were discovered. Barry, who was never charged, accused the cops of planting the contraband and claimed he was waiting to meet a friend who needed counseling. But his incipient campaign was scuttled, and he soon separated from his fourth wife.

Two years later, in an impressive display of resilience, he won the Ward 8 council seat, where he continued to serve at the time of his death.

“I shouldn’t have gone up to that hotel room,” Barry said five months ago at a Washington dinner celebrating the publication of his memoir, Mayor for Life. “ I apologized to Rasheeda Moore and her family. I apologized to Christopher, my son, and my wife, Effi, and got married again. And this is a country, a society, of second chances, third chances or fifth chances. When Jesus was asked, how many times can you forgive people, He said, ‘Seventy times seventy.’ ”

Barry, who will undoubtedly be remembered in the nation’s capital as a towering figure for good and ill, always had a flair for attracting attention, so it’s not surprising that his permanent leave-taking was being marked on Sunday night by a long-scheduled broadcast of an Oprah Winfrey interview on her eponymous cable channel. Or that 3,000 turkeys will be handed out in his name on Tuesday to needy families—a Ward 8 Thanksgiving tradition.

Indeed, he was greeted by his constituents as something of a household god. “I know a woman who says Marion Barry could crawl down the street buck-naked, and she would still vote for him,” Barry’s close friend, Charles Moreland, told me at the dinner. “In every adversity there’s opportunity—that’s the lesson of Marion Barry.”