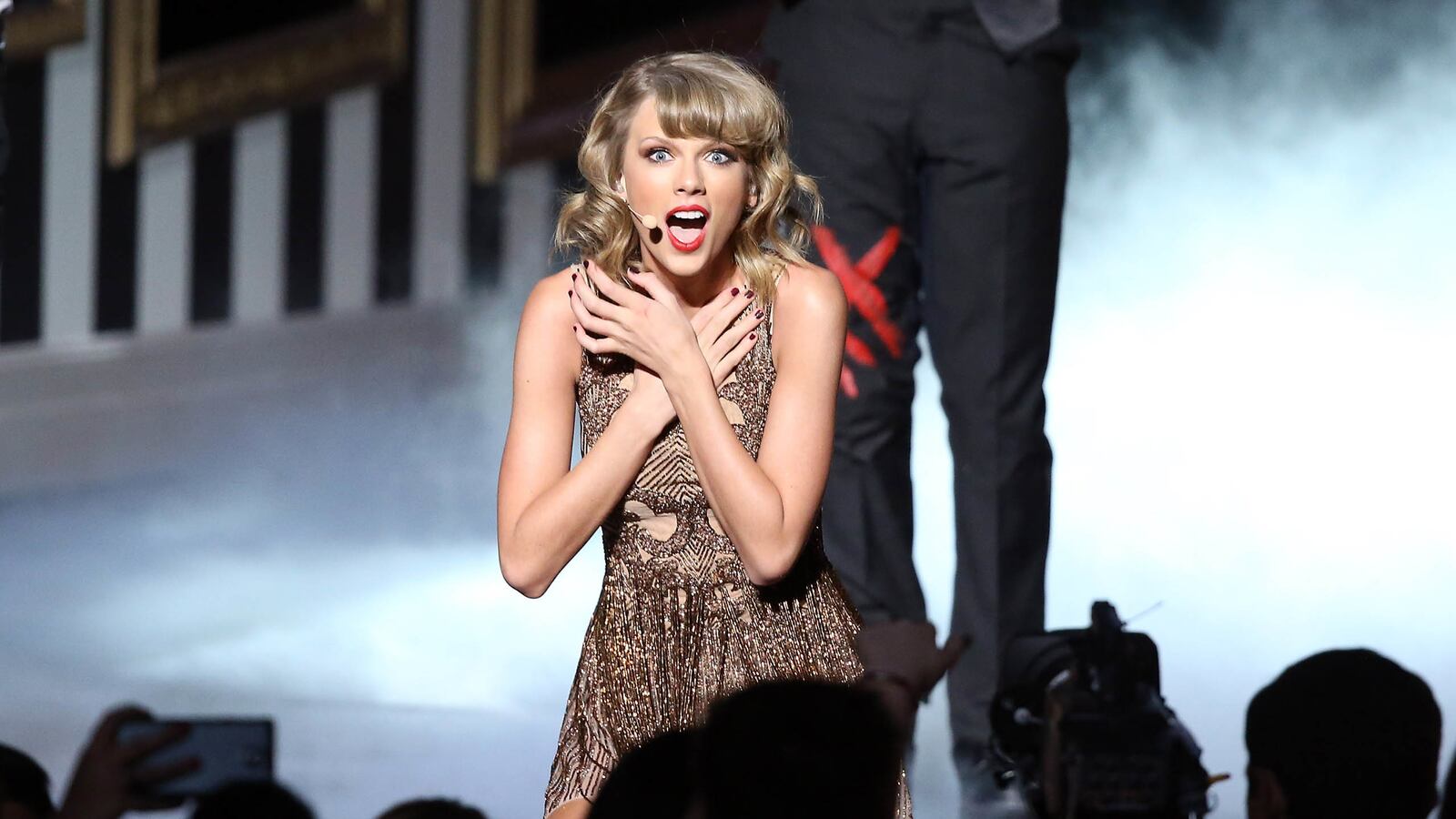

I was a big fan of Taylor Swift at the AMAs, and not just because she is even better at doing an improvised awkward goofy dance than I am.

It’s also because, believe it or not, Taylor Swift is the first artist I can remember in a long, long time to make a meaningful political statement while accepting an award at the AMAs—not speaking out against war or in favor of feeding the hungry or other relatively easy statements for pop stars to make, but a political statement about an issue affecting the music industry.

Awards shows are generally, despite their pretensions of celebrating the “craft,” starkly terrified of ever letting the audience get a peek at how the sausage gets made. Talk of money-grubbing commerce is banned from awards shows, which is why a deliberate troll like Ricky Gervais led with it in his 2011 Golden Globes monologue.

But the ever-positive Swift wasn’t trying to get a rise out of anyone when she dissed Spotify in all but name.

She was making a serious point about a serious divide within the music industry and music fandom, one that’s been making waves ever since her choice to pull all her albums off of Spotify. The split between the music fans who think digital streaming services are going to save the music industry and the fans who think they’re going to kill it.

The Internet cool kids are, of course, rallying against Swift en masse. On the one hand there’s the entitled fans who tweet their rage that they can’t get their music how they want it, when they want it; on the other hand there’s the CEO of Spotify making a very serious case for streaming being the Future of Music and Swift’s actions being a futile attempt to turn back the clock.

I am a child of the Internet. I was the kid making a tidy profit burning CDs for all my friends at two bucks a pop back during the Napster heyday in 2000. And, as an Asian kid with a very limited allowance whose parents disapproved of “rock and roll,” Napster was solely responsible for me developing any musical tastes more recent than Wagner. If anyone should be grateful for the modern world of “free” music it’s me.

And remix culture, the phenomenon by which a cultural artifact “goes viral” and spawns a million takeoffs and variations within a short time, has produced tons of things I love. I’m totally the guy who had playlists full of mash-ups before Glee took them mainstream. I truly think homebrew music videos on YouTube are one of the great art forms of my generation, and that Neil Cicierega is a national treasure.

As such, it would be irresponsible of me not to point out that there’s an argument that this ecosystem of freely shared, freely distributed information leading to infinite remixes—this postmodern world I love so much—may, in fact, be ruining everything.

If I could toot my own horn for a moment, I was one of the founding members of freeculture.org at the Swarthmore chapter that helped get the ball rolling back in the 2000s. If there’s any old-school hacktivists in my audience, the OPG, Pavlosky and Smith v. Diebold, Inc. case that helped set a precedent against spurious DMCA takedown notices involved one of my best friends at the time (Nelson Pavlosky) and my freshman roommate (Luke Smith).

I don’t regret my time in the “Free Culture” movement, and I still broadly believe in its tenets—that stringent enforcement of intellectual property law does more harm than good, that the freedom to “remix” has created many great works of art and commentary, etc. But, like Jaron Lanier, I’ve come to have a mixed view of the results of treating “Free Culture” as a black-and-white good-vs-evil battle.

Much like how I, like pretty much every other dude on the Internet, once unquestioningly championed “freedom of speech” as the highest of all human values and “censorship” as the ultimate evil, only to eventually find out that “freedom of speech” without limitation has turned much of the Internet into an unredeemable cesspool of lies, abuse, and outright crime.

Same with the idea of truly “free” cultural creativity. Yes, philosophically speaking, ideas shouldn’t belong to anyone, they should belong to everyone who passionately cares about them. Yes, it’s infuriating when someone makes something beautiful, or hilarious, or just plain cool and it gets shut down because of “the lawyers.” Yes, part of me would love it if the world looked like a giant free-for-all forum where anyone could fearlessly remix anything they liked.

But we live in a world where the main reason that doesn’t happen is that creators need to make money in order to buy groceries and pay rent. And the “freer” our culture is, the harder it is for that to happen.

In 2004, when people told us that piracy—or, as we insisted on calling it, unauthorized digital sharing—was going to destroy the revenue stream that made the creative economy possible, we called it irresponsible speculation, and speculated that “alternative funding models” would easily close the gap. Every geek in the Free Culture movement had the idea for Kickstarter years before Kickstarter actually existed. Everyone was confidently pointing to Radiohead’s pay-what-you-want distribution for In Rainbows in 2007 as the wave of the future.

Well, it now is the future, in 2014, and the news isn’t actually very good.

Writers’ revenues? Down 29 percent since 2005, according to a Guardian survey of book authors. Musicians’ revenues? The whole industry is now making its lowest revenues ever, since the RIAA started counting in 1973. Movie theaters reported they’ve had their worst summer this year since 1997. Hollywood has become so paranoid about its profit margins it’s almost impossible to make a major feature film that isn’t a remake or an adaptation; Steven Spielberg had such a hard time getting the funding to make Lincoln that he predicts an upcoming “implosion” in the industry.

The idea that paid streaming services, supported by advertising or subscription fees, would save music by being a profitable alternative to piracy has mostly fallen flat. Spotify confidently predicted that Taylor Swift could’ve gotten $6 million if she’d released 1989 to stream; the CEO of her label shot back that she actually only made about $500,000 from domestic streaming last year and making 12 times that from one new album release seems unduly optimistic.

Moreover, as the above interview points out, Taylor Swift is the most popular artist on the charts today. If she’s only making a half million every year from Spotify, how much is your average mid-lister who’s not on the front page of Time magazine making? A talented, well-liked artist like Zoe Keating makes about $6,000 for being streamed over 400,000 times.

That’s, it turns out, what the market will bear when you have to rely on what sponsors are willing to pay for ad-supported streaming or what the tiny minority of paid users are willing to pay in subscription fees. Straight-up asking how much customers are willing to pay isn’t much better—if you’re not Radiohead you tend to make a pittance, with a surprisingly brazen majority of fans openly telling you they’d like to pay nothing.

Crowdfunding—what we Free Culture geniuses once called the “ransom model”—hasn’t been a silver bullet either. For every awesome Kickstarter success story the landscape is littered with disappointments and failures, the inevitable result of having to try to sell a product to a huge crowd of people before you have a cent to start making anything at all.

The upshot is that while ideas and art and information may want to be free, rent and groceries and recording equipment don’t. And for all the massive flaws, both philosophical and practical, in the old-school corporate-owned pay-per-physical-copy model of the creative industry, most of the time if you made it past the gatekeepers and were a relatively successful artist you could be confident of being paid a living wage for your work.

That’s simply no longer the case, and all the “disruptive” technologies in the world haven’t come up for a viable replacement for the old model. David Lowery of Camper von Beethoven and Cracker made this case in a viral post from 2012.

He’s as much an extremist against “Free Culture” as I was once for it, and I don’t agree with him about everything, but it’s hard to argue with the brute statistical fact he puts forward that the number of working professional musicians has dropped 25 percent since 2000. Not to mention his anecdotal evidence of fellow mid-list musicians losing their homes, going into debt, falling into despair as their revenues plummet.

I can share similar stories from my own limited experience as an aspiring actor in a “regional” market, where it’s become nearly impossible to get people to pay money to buy tickets or DVDs of indie films, making it nearly impossible to pay actors in indie films, leading to project after project done “for exposure” until actors give up and do something more rewarding with their time like take a second retail job to pay the bills.

But it’s ultimately not about the money, exactly. The money is just a symptom. The reason it’s so hard to get people to pay for music, or movies, or writing is precisely the thing that everyone celebrates about the Internet—that art is available at the click of a button, that we’re constantly, addictively sharing and re-sharing and remixing everything, that our culture is soaked in art like the air we breathe.

That’s the problem. Air is everywhere. Air is free. Air doesn’t come from any specific person and isn’t the result of any individual effort. Asking the consumer to interrupt the seamless flow of sharing to take note of an individual creator and compensate them for their effort totally harshes the buzz.

The very nature of going “viral” is that it requires the content to be instantly, freely shareable. That precludes paying much mind to attribution or compensation. Viral content is content that feels like it belongs to everybody.

That’s not a bad thing. I love seeing memes take off and spark mutations and parodies and homages. The sheer freedom I have to, say, see and hear a dozen different covers of my favorite song instantly, on impulse, without having to go poring the shelves of a record store for them is a creative gift that fans only one generation ago could only dream of. The fact that I can make a cheesy lip sync video and show it to all my followers in the course of one night— that I can create and share something with thousands of people with less cost and effort than at any other time in history—is magical.

But let’s think about that Taylor Swift lip sync video I did. It’s 100 percent based on the lyrics and music Taylor Swift wrote and recorded. It’s only interesting to anyone because of the pre-existing cultural significance of “Shake It Off” based on Taylor Swift’s own popularity. It is, in every sense, a “derivative work” of Taylor Swift’s track, and in fact includes Taylor Swift’s track in its entirety such that someone who just wants to listen to it can click on my video to do so.

And I didn’t have to ask Taylor Swift’s permission, or think about compensating Taylor Swift or her record label at all to make it. I just uploaded the video with the embedded audio track, YouTube detected it was copyrighted and automatically applied the Standard YouTube License to it to pop up ads that get Taylor Swift paid $0.00064 every time someone streams it.

Does it matter whether Taylor Swift wants me to inflate my Internet notoriety by doing a dumb thing where I lip sync to her music? Or that she probably, given her attitude toward Spotify, wants more money than that per stream if she has to let me do it?

Nope, because Google’s market share is enough that any major record label pretty much has to agree to let their music fall under the YouTube license, at least in the United States, lest that label be seen as the stick-in-the-mud ruining all the cute homemade music videos with their DMCA claims.

You pretty much have to make stuff available for no monetary cost to the consumer and as conveniently as possible, or your fans will abandon you. Just like newspapers felt they had to put their content out for free because paywalls drove away readers, and by so doing steadily hollowed out their subscriber base until print newspapers collapsed as an industry.

In Swift’s words, “If you create music someday, if you create a painting someday, someone can just walk into a museum, take it off the wall, rip off a corner off it, and it’s theirs now and they don’t have to pay for it.” That’s just the world we live in.

It’s not like Taylor Swift has blocked people like me from using her music on YouTube, or seriously gone after people outright pirating her stuff on Grooveshark or Soundcloud. But even the minor inconvenience of not being able to instantly stream her music off of your iPhone as a Spotify subscriber has painted a target on her back. We don’t just want to be able to grab whatever we want whenever we want and use it however we want, with no transaction fees and no fuss. We need to. It’s our right. We’re entitled to it.

I don’t regret making that silly YouTube video. (Well, I sort of do, but not for this reason.) I’m still a Free Culture kind of guy. I still listen to the Grey Album all the time. There are remix artists out there who deftly combine threads from vastly disparate cultural phenomena and alchemically transform them into new works of genius.

But then, you know, there’s everyone else. The typical music video you find on YouTube is colloquially called “YouTube Poop” for a reason. For every video that’s genuinely entertaining and clever you get dozens of predictable, clichéd, sometimes obscene parodies. Now that everyone knows what mash-ups are, any mash-up collection will have over a hundred of the same Top 40 tracks mashed up with each other over and over again.

We’ve seen fully half the U.S. population sing “Let It Go” and the other half reenact the Harlem Shake. To paraphrase Douglas Adams, there was a time when the resources to track down and license a patchwork of cultural ephemera were costly, and so a clever remix or reappropriation was like a spring of clear water in the desert. Now? It’s endless rain and soggy mud, everywhere you look.

We live in a world where news stories and op-eds get summarized, aggregated and reblogged by outlet after outlet until every platform is a homogeneous mush of “content.” Where the idea of authorship and sourcing has faded and it’s become natural to just cite factoids as coming from “Wikipedia” or “Reddit” or “Tumblr.”

I remember the weird feeling of being surprised when one of my favorite pieces of Internet “creepypasta”—delightfully mysterious weird writing that gets shared and re-shared on random forums—turned out to have an author who had never been compensated or credited for his work.

I remember how much of a jerk I felt like when the research I’d done “on Wikipedia” for my article about Disco Demolition Night turned out to be mostly piggybacking off of a specific paper by Dr. Gillian Frank that had been copied onto Wikipedia by anonymous editors. Dr. Frank contacted me and was justifiably miffed that I was, essentially, riffing on her work without giving her any credit—and as a lifelong denizen of the Internet who was used to information just being “there” as a result of my Google searches, I hadn’t even realized I was doing it. (Something I’ve since tried to correct.)

Eric S. Raymond used the analogy of The Cathedral and the Bazaar in the context of software development, to talk about the contrast between the unified vision of a singular genius vs. crowdsourcing the work to a huge mob of fans, and defending the latter as the way of the future.

We now live in a world where the bazaar has pretty much won hands-down, and we get to see the ways in which the bazaar, despite how cheaply and efficiently it can create endless quantities of “content,” kind of sucks—how, much like real bazaars, you end up seeing a lot of shoddy bootleg knockoffs of the same designs because everyone’s trying to piggyback off of everyone else’s business.

The cathedral architects are still out there—I don’t know if Taylor Swift would qualify, though I’d argue she does—but they live in a world where as soon as their work is put out for consumption it will be remixed, mashed up, parodied, dissected into a standardized list of “tropes.” Their work has never been easier to tear away from their byline and recycle without attribution—and so, if nothing else, getting the steady income needed to make that work possible has never been iffier.

So even if Taylor Swift’s bold screw-you to Spotify is tilting at windmills, it’s tilting at a windmill that’s been grinding down artists like her for over a decade now, and I fully support it. She’s a hero, all the more so if sabotaging her own “exposure” and angering her fans this way is something only Taylor Swift could get away with.

Because yes, as a fan, and as an Internet-addicted device-addicted 21st century digital boy particularly, 1989 not being on Spotify is annoying. It’s annoying to not be able to seamlessly “pull up” any Taylor Swift song I want to listen to at a whim. It’s annoying to hit that speedbump of having to stop and think about whether I want to listen to this particular song right now and realize that if I do, I have to dig into my pocket and give her a whole $1.29.

I have to think about the fact that the reason I have to do this is that Taylor Swift wants me to do it, because her music isn’t just floating around in the atmosphere as part of “the Internet” or “the culture”—her music was made by a specific human being whose desires and intentions I have to take into account, if only for the two minutes it takes to go to iTunes and download the track.

And if, in our modern world, that’s an insufferable annoyance, maybe we should spend more time being annoyed.