You do not have to be a Christian to be gripped, shaken, jolted, and kept up at night by The Stand—Stephen King’s “long tale of dark Christianity,” as he called it. But to feel the book invade you, in the way of the greatest and worst of books, more than the presence of the Lord is required. You must have felt—maybe once in your life, maybe last night; maybe right now—the awful slow-motion instant when you realize that evil has found you.

One moment, you’re going along, sinning as humans do. The next—well, the next moment is different. Unlike all others. With the change of tempo that turns ordinary dreams into uncontrollable nightmares, you pause, seeing yourself…from a standpoint somewhere outside yourself. And from that outside-place, hovering in the night, “you” turn…slowly…out toward the world, across the elevated city or the empty fields or the shadowed bedroom window. There, out there, it is: the Eye.

“Turning,” King writes, “in the darkness. Looking.” A “hot presence,” a “dreadful red Eye.” It knows. It knows you. And you know it knows. You know you have been spotted—marked. Possibly forever.

Tolkien, channeling something similar, conjured the Eye of Sauron. But in the 1970s, our best decade (with good reason) for apocalyptic literature, King set out to write “a fantasy epic like The Lord of the Rings, only with an American setting.” He discovered no goblins or orcs are necessary—just us humans, and the all-too-familiar supernatural powers that take us where they find us. There, so taken, caught in the act, flat-footed, we are obliged to make our stand.

We might be anyone from a sociologist to a rock musician to the oldest woman in the world—just a few of The Stand’s many heroes. Could we be a writer? Or worse still, an actor?

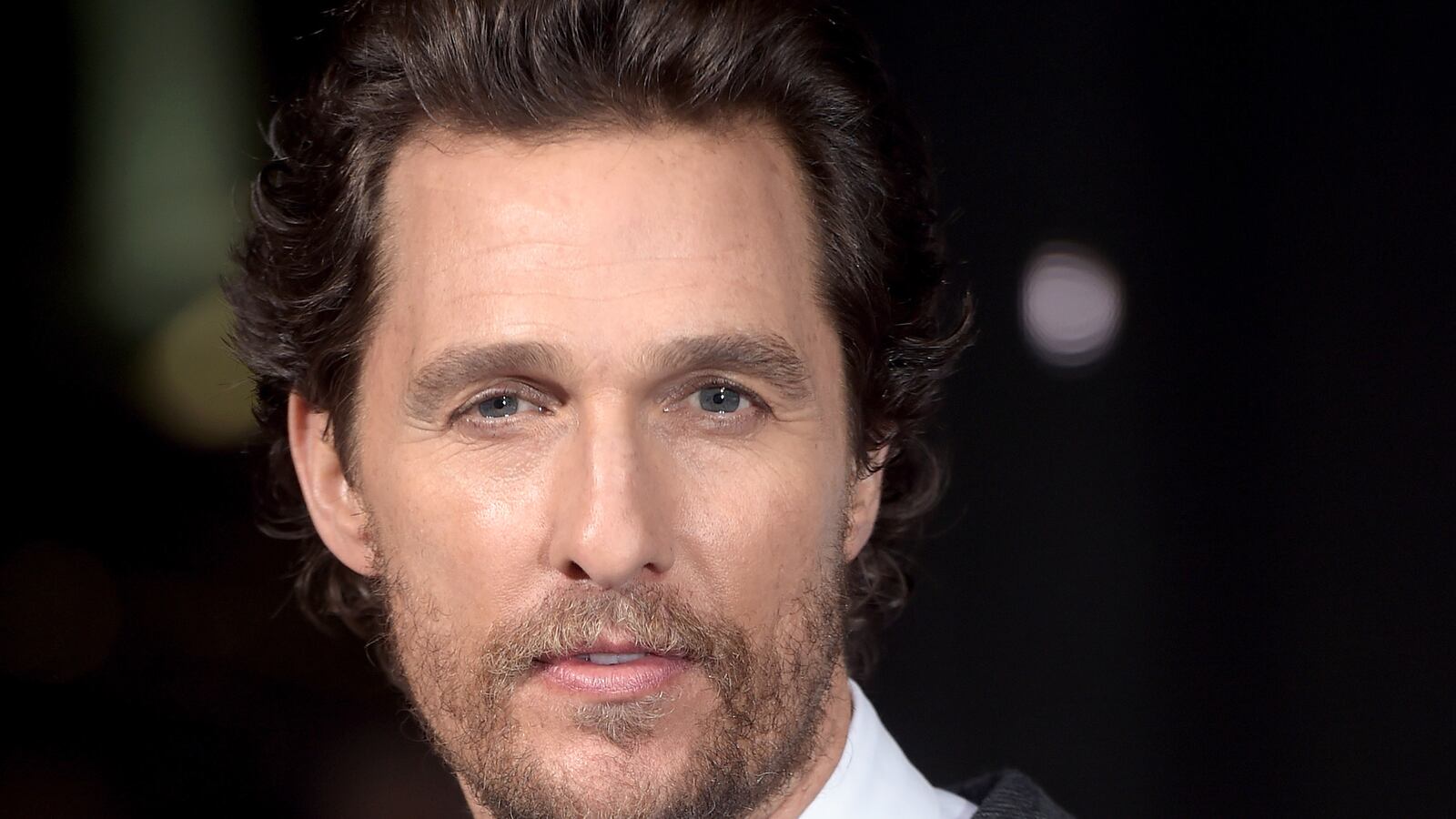

I think so. And I think Matthew McConaughey does too. “Sometimes,” he is fond of telling the press, “the target draws the arrow.” So it is right and proper that he has been tipped to star as Randall Flagg, The Stand’s diabolical all-American villain, the hovering Walkin’ Dude with the evil Eye, in what appears to be a full-blown big-screen adaptation greenlit by Warner Brothers.

If the past decade turned out to be a good time for the Lord of the Rings franchise, this decade is all but begging to revisit The Stand. No matter its epic grandeur and ultimate spiritual themes, the Rings/Hobbit juggernaut could not—like last decade’s Failure to Launch-era McConaughey—escape the gravitational weight of its own indulgent, and self-indulgent, cheese. Since the ‘70s, that problem has threatened to define and destroy both romantic fantasy (ahem, Led Zeppelin) and romantic comedy (cough cough, Grease).

Now, deep into the golden age of TV dramas grittier and lengthier than the pretty-good ’94 miniseries take on The Stand, we, like McConaughey, have grown gaunter, more haunted, and much less romantic. However immature, we have not failed to age. Our awareness of death is strangely sharper now than even on 9/11; we have come to realize how death can so often contentedly wait, time on its side. For the occasional shock and awe of mortality, there is day after day of creeping awareness, a sense that however long a person or a culture or a system can run, it cannot hide from the End.

However we strain to distract ourselves, our consciousness of death heightens our awareness of evil. Evil is a convenience store of death. Yet, rushing through life as we do, we can be hard to pin down even for “the Imp of Satan,” as The Stand’s heroine, 108-year-old Mother Abigail, calls Flagg. He, it, lacks death’s patience. Sometimes evil must jeer at us from life’s alleys, “beckoning like a pimp,” as one character puts it when Flagg comes to him in a dream.

But sometimes we go evil hunting. Sometimes, although we would hate to admit it, we think we can hunt evil for sport, like a hillbilly, not for salvation, like a vampire-killer. Get a thrill, get off a lucky shot, take home a trophy, put it up in a secret chamber of our heart. Cheat, in other words—on God, on our fellow man, ultimately, on ourselves.

I suspect, but I cannot prove, that McConaughey knows this, too. He knows how to play human rust—the creeping, spreading, subversively insistent presence cruising for evil in the dank miniseries known as True Detective Season One. He wrote his own 450-page character guide to Rust Cohle. In a perhaps not-so-strange coincidence involving his real-life marriage and fatherhood, McConaughey aged into doing his homework about evil’s cheatin’ ways, and ours.

That cycle of delirium—of pandemonium, let’s say—was summed up in McConaughey’s mini-briefing to Leonardo DiCaprio in The Wolf of Wall Street, where he played an old, coke-fueled dog devoted body and mind to new tricks. “Revolutions,” he explained. “Keep the clients on the Ferris wheel.” There, here, “the park is open twenty-four/seven, three-six-five, every decade, every goddamn century. That’s it—the name of the game.”

Intentionally or not, McConaughey channeled the Walkin Dude as the driving dude of Lincoln’s new ad campaign, a shadow-laden figure with the Flagg-like ability to entrance with a cryptic and cosmological ambiguity. “I know there are those who say you can’t go back,” he whispers in the ad. “Yes you can. You just have to look in the right place.”

Flagg, an ageless master of inciting revolutions paid out in blood as well as treasure, couldn’t have said it better. “He had sat on a hundred different Committees of Responsibility,” writes King. “He had walked in demonstrations against the same dozen companies on a hundred different college campuses.” Flagg’s “pockets were stuffed with fifty different kinds of conflicting literature—pamphlets for all seasons, rhetoric for all reasons.”

Imps of Satan: they’re just like us! In a culture where nothing is devoutly shared but rancor, our struggles over identity, on campus or in the streets, beckon perversely to an evil that sees through them all. “In New York,” writes King, Flagg “was known as Robert Franq, and his claim that he was a black man had never been disputed, although his skin was very light,” and though in Georgia, “in his white sheet, he had participated in two rapes, a castration,” and other Klan crimes.

In Atlanta one hundred years ago or Staten Island this summer, evil relishes toying with race, America’s great repository of dark twisted fantasies. Too weakened by false guilt and true memory to forgive or forebear, we license the presence of evil under the pretext of circumstances. About our Eric Garners—too fat, too scared, too noncompliant, too many kids—there are always, as Flagg knows well, excuses.

At the turn of this decade, Kevin Baker, a different kind of novelist, called 1978—the year The Stand was published—New York’s greatest year. “There was nowhere to go but up,” he wrote. Unlike today’s chokehold of a condo-state, that Big Apple “was accessible to all, open to all. If that created problems, it was also a place where everyone had a stake, where everyone was a full citizen.” Today, the ‘70s echo back at us clamorously, from Ferguson to UVA to New York and beyond—in all their openness, to the fullness of humanity and the fullness of evil alike. Then as now, we all are at stake, and sooner or later, we all must make a stand.

Faced with crippling writer’s block, King only managed to finish his opus by killing off half of its principal cast. They were holding too many meetings, he realized, descending into politics instead of ascending to reckon with Flagg. But Flagg, too, comes apart in his machinations, bent ever more fully on political domination. His descent is literal: by the end, he can barely levitate. Politics, King warns us, is grounding, all too grounding. Our petty struggles for power invite a supernatural response—be it Flagg’s hellacious affection or the awful grace of God.