The news that Charles Manson and 26-year-old Afton Elaine Burton have obtained a marriage license has piqued the public’s curiosity, with the media scrambling for any semblance of insight into the woman who would be Mrs. Manson. But beyond the initial desire to understand why someone would want to wed an 80-year-old convicted murderer, destined to spend the rest of his life in prison, the notorious inmate’s pending nuptials have raised several basic questions about what it’s like to get married behind bars.

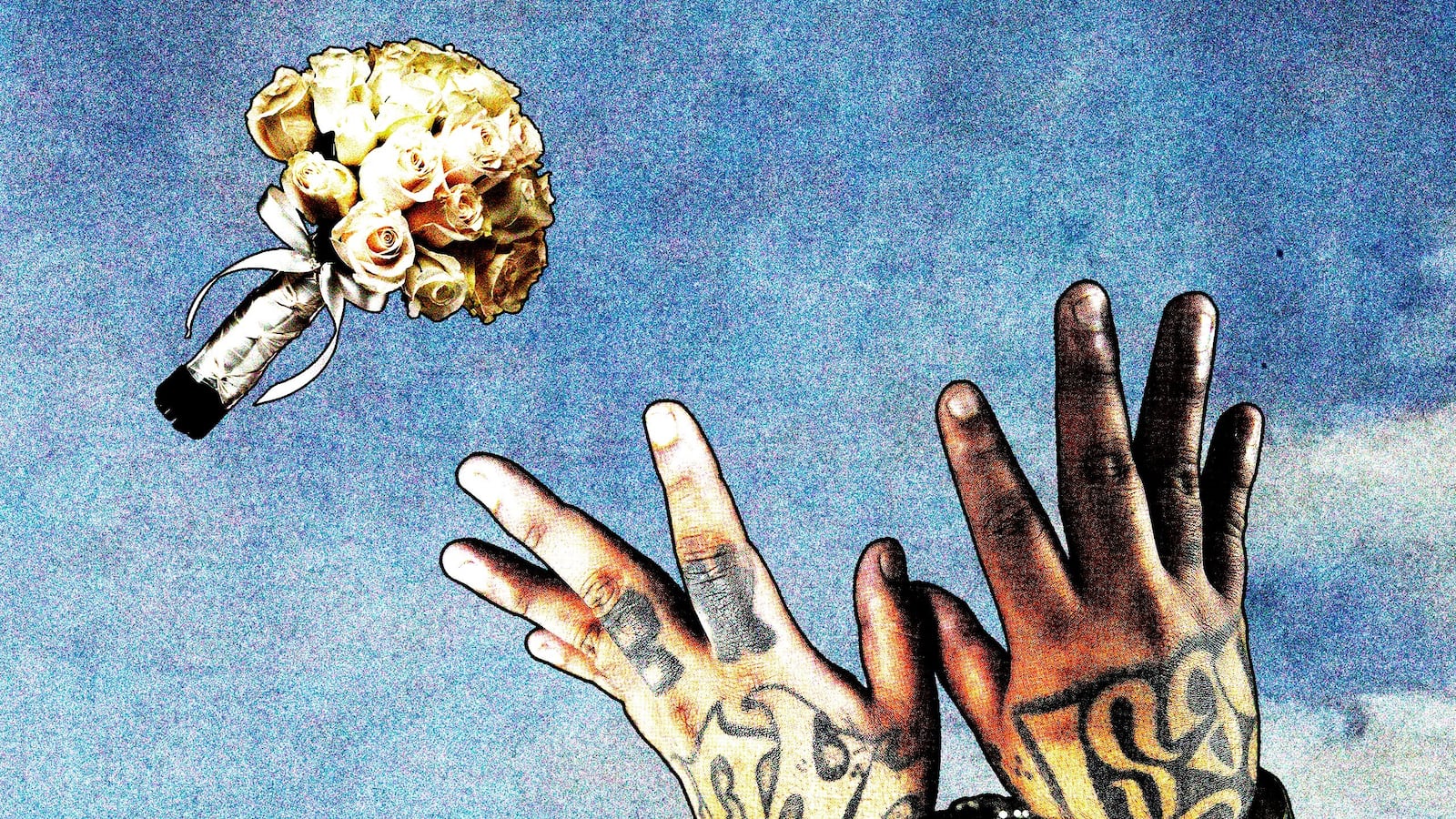

Marriage in the United States has become an industry valued at more than $50 billion, with the bill for the average wedding adding up to about $25,000. But flowers, food, booze, linens, entertainment, and other costly components of a typical wedding are forbidden inside the walls of most prisons and jails. Stripped of these frills, the only real expense of a prison wedding is the officiant. For fees ranging upward of $100, the officiant is the person who makes a prison marriage happen. From accompanying the non-imprisoned spouse to the county clerk’s office to purchase a marriage license to helping both members of the couple fill out the sometimes complicated paperwork needed to secure a prison’s permission for a wedding, and performing the ceremony, these prison wedding officiants have cornered a very niche, but necessary market within the marriage industrial complex.

A simple Google search for “prison wedding officiant” produces a long list of links to websites ranging from the cut and dry description of fees and services, to flowery promises of beautiful and personalized ceremonies surrounded by moving images of wedding bells and doves against a lavender background. Some websites play up the love theme heavily, obviously targeting the female half of the couple (who is often, but not always, the one on the outside), giving the impression that anyone can have their dream wedding, even if their fiancé is incarcerated.

In reality, prison weddings look nothing like the fairy tales depicted on TV and in bridal magazines. But to Reverend Alan Joplin, they are much more special.

“These are two people who have made decisions in circumstances that are unbearable, to want to be with each other the rest of their lives,” said Joplin, a retired United Methodist pastor who began officiating weddings in jails and prisons four years ago. “It will never be like they are getting married outside of prison, but I want them to feel something special about what’s going on.”

To make his ceremonies special, Joplin, who is based in Phoenix, Arizona, likes to spend as much time as he can getting to know the half of the couple not living behind bars. The first thing Joplin needs to find out before he will agree to officiate a wedding is why his potential client is in prison. He draws the line at child molesters, but doesn’t discriminate against convicts of any other crimes, even murder.

“We all need a connection,” Joplin said.

Ahead of the wedding, Joplin tries to meet with the non-incarcerated partner three or four times to learn about their relationship, why they want to get married, and whether they want a religious ceremony, to read their own vows, or just make it a “quickie”—cutting straight to “I now pronounce you man and wife.”

Though a prison chaplain typically has to sign off on weddings, Joplin said ceremonies generally don’t take place in the chapel. Some prisons reserve the dayroom or common area for weddings. At others, the ceremonies are held in the visitors area, surrounded by other inmates and their loved ones, the bride and groom occasionally even separated by glass.

Curating the perfect guest list isn’t usually a problem, Joplin said, as he’s never presided over a ceremony with more than eight or nine guests, most of them family and typically all from the bride’s side. Those who do wish to attend, however, must be pre-approved for visitation ahead of the wedding day.

The majority of the Joplin’s clients are couples who were together before one of them got locked up. Often they have children together. Joplin said he’s only received one call from a woman looking to marry a man who she met while he was in prison. The woman had accompanied a friend who was visiting her boyfriend when she met the inmate she would marry. They began exchanging letters and she developed a relationship with his relatives on the outside. He was nearing the end of his sentence, but the woman enlisted Joplin to marry them before he was released.

In none of the weddings Joplin has performed did the inmate have more than five years to serve.

One piece of the prison wedding world is comprised by people like Joplin, retired or active ministers, for whom officiating inmate weddings is just another part of their religious and community service. But it is also a business.

Jean-Claude Bensoussan got into the prison wedding business 12 years ago. After retiring from a career in investment banking, the Los Angeles-based French transplant became a notary and started a company providing mobile notary services to corporations. It was through this work that Bensoussan discovered there was a demand for ministers to perform weddings at jails and prisons. He became ordained and created a new service for his company. Though he employs about 25 people, Bensoussan is the only one who performs prison marriages—and it’s a gig that keeps him busy, officiating an average of 20 to 30 weddings each month. He estimates he’s married over 1,500 couples a little more than a decade. The minimum fee for Bensoussan’s services is $500, which includes going to the county clerk’s office to purchase the marriage license and the actual ceremony. For inmates located outside the Los Angeles area, a wedding with Bensoussan can run up to $2,000 or $3,000.

Like Joplin, Bensoussan said most of his clients were together before they were separated by bars. In situations where the inmate is an immigrant and at risk of deportation, Bensoussan requires some kind of substantial proof that the relationship is legitimate. Otherwise, he decides whether or not to perform a wedding based on how comfortable he feels with the spouse on the outside.

“I tell them they are ruining their life, but I will not refuse to do it,” Bensoussan said. “I will do my best to tell them they are making a mistake, but if there is nothing I can do to convince them, I will do the marriage. Sometimes I don’t understand how they think.”

Though he tries to discourage prison weddings in general, Bensoussan said it does not matter to him what crimes his clients have committed. In fact, he’d rather not know. He has only turned down a few weddings, claiming to perform around 80 percent of the prison marriages in the Los Angeles area. Still, Bensoussan said that if Charles Manson’s fiancé came calling, he’d most certainly turn her away.

“The publicity around it is unbelievable,” Bensoussan said of Manson’s engagement—and not in a good way. “This is a notorious inmate. We all know what he did.”