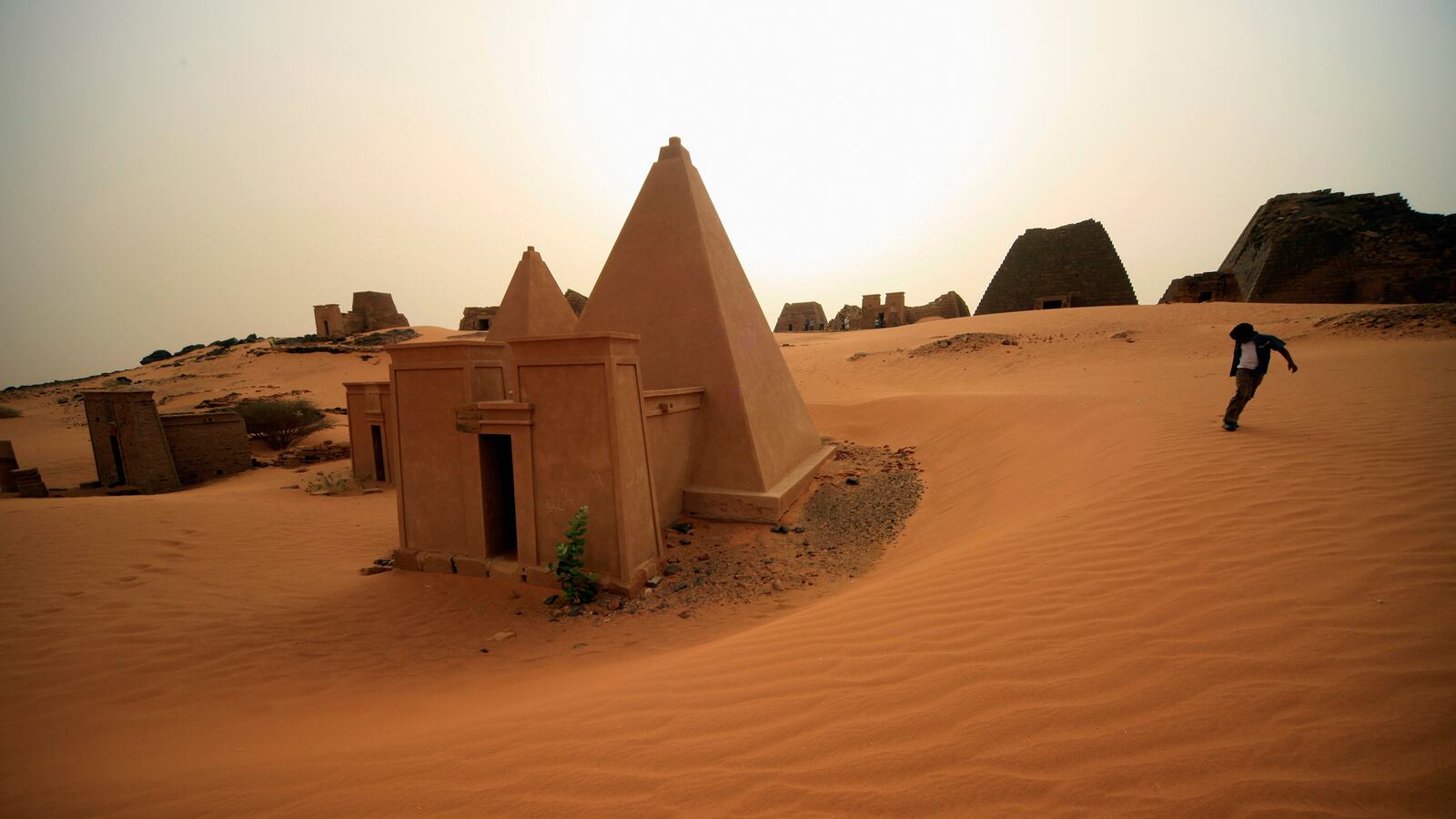

Egypt may lay claim to the world’s most famous pyramids, but 800 miles away from Giza, there are hundreds of similar peaks dotting the dark orange sands of Sudan, virtually undiscovered by the photo-snapping tourists who have overrun their northern neighbors.

Some 2,000 years after the Pharaohs first constructed their pyramids in Egypt, the rulers of what is now Sudan recruited Egyptian artisans to build their own smaller, yet more numerous, pyramids in Meroe. For more than 1,000 years, beginning in the 8th century B.C., the area was the heart of the Kingdom of Kush, which crumbled when Christianity arrived to the region in the 6th century A.D.

On the banks of the great Nile River, Meroe’s Royal Necropolis, and more than 200 pyramids, temples, and palaces have been excavated, many of them covering tombs of past kings and queens. They’re topped with classic Egyptian motifs, like birds and solar disks, and represent the melting pot of cultures that once came to a head in the long-lost kingdom. In a recent visit, the Guardian describes the scene as scattered peaks of temples and tombs sprinkled across a burnt landscape of rippling sand that the government of Sudan has been reluctant to promote for tourism.

Thousands of years ago, Meroe was a thriving hub of trade and home to some 25,000 residents. The city served as a crossroads for African, Mediterranean, and Middle Eastern cultures. Because of this, an unusually diverse mix of relics have been found buried in the area, including Greek pottery, French wine jugs, and Syrian glass. An artistic style that has been compared to Cubist Expressionism was also discovered across the site.

Unfortunately, dozens of pyramids are missing their peaks thanks to an overeager, gold-seeking explorer. The pyramids were first spotted by Westerners in 1772, and 60 years later, the Italian Giuseppe Ferlini arrived at Meroe and hacked off the top of 40 pyramids in his hunt for treasure. Before preservationists could put a stop to it, he and other looters had raided and destroyed precious relics buried at the site. Ferlini’s findings, including writings and bas-relief works, were taken out of Sudan and bought by British and German museums.

It wasn’t until the 1990s that the language on these Meroitic scripts was first deciphered, but, by that time, many ancient writings had been destroyed due to flooding from the nearby river and dam projects. But the site has seen little of the decimation from heavy tourism that has plagued the northern pyramids of Giza in Egypt.

Overall, few travelers have made the trek into the desert of Sudan to see these architectural wonders. In the mid-1990s, some visitors did begin to show up due to the construction efforts of Osama Bin Laden. The terrorist leader had moved to Sudan in 1991 and invested in infrastructure, before he was forced out of the country and relocated to Afghanistan. One of his projects resulted in a new road from Khartoum, the capital of Sudan, to the monuments at Meroe.

The path may be there, but current travelers to Sudan face a bureaucratic nightmare of permits and road blocks. To overcome these impediments, at least two tour operators bring visitors into the region. And, in the past decade, a luxurious campsite has been constructed to house visitors to Meroe, close enough that overnight guests say they can peek out of their tents and see the pyramids.

The ruins became certified as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2011, but, despite the amenities and access, few have shown up to marvel at the wonders of Meroe. According to a ticket seller who spoke to The Guardian, the site still receives only 10 visitors a day, on average.

Sudan has been plagued by years of political instability, which has prevented tourism from gaining traction. For the past 25 years, a massive civil war has literally divided the country into two separate entities. And trouble continues in the north. This October, there were reports that the Sudanese military raped more than 200 women and girls in the Darfur region. And just Tuesday, Sudan’s government failed to agree on a ceasefire with rebel groups as clashes continued.

The pyramids of Meroe await a day when stability will allow outsiders to peek at a forgotten ancient kingdom. But for now, the path remains difficult, and some even speculate that authorities don’t want visitors to the area.

“When the government have occasionally talked about tourism, they talk about Islamic tourism,” a local analyst told the Guardian. “You don’t get the impression they celebrate the history and things they’ve got on their doorstep. I think there’s a reluctance to embrace what they would regard as heathen worship.”