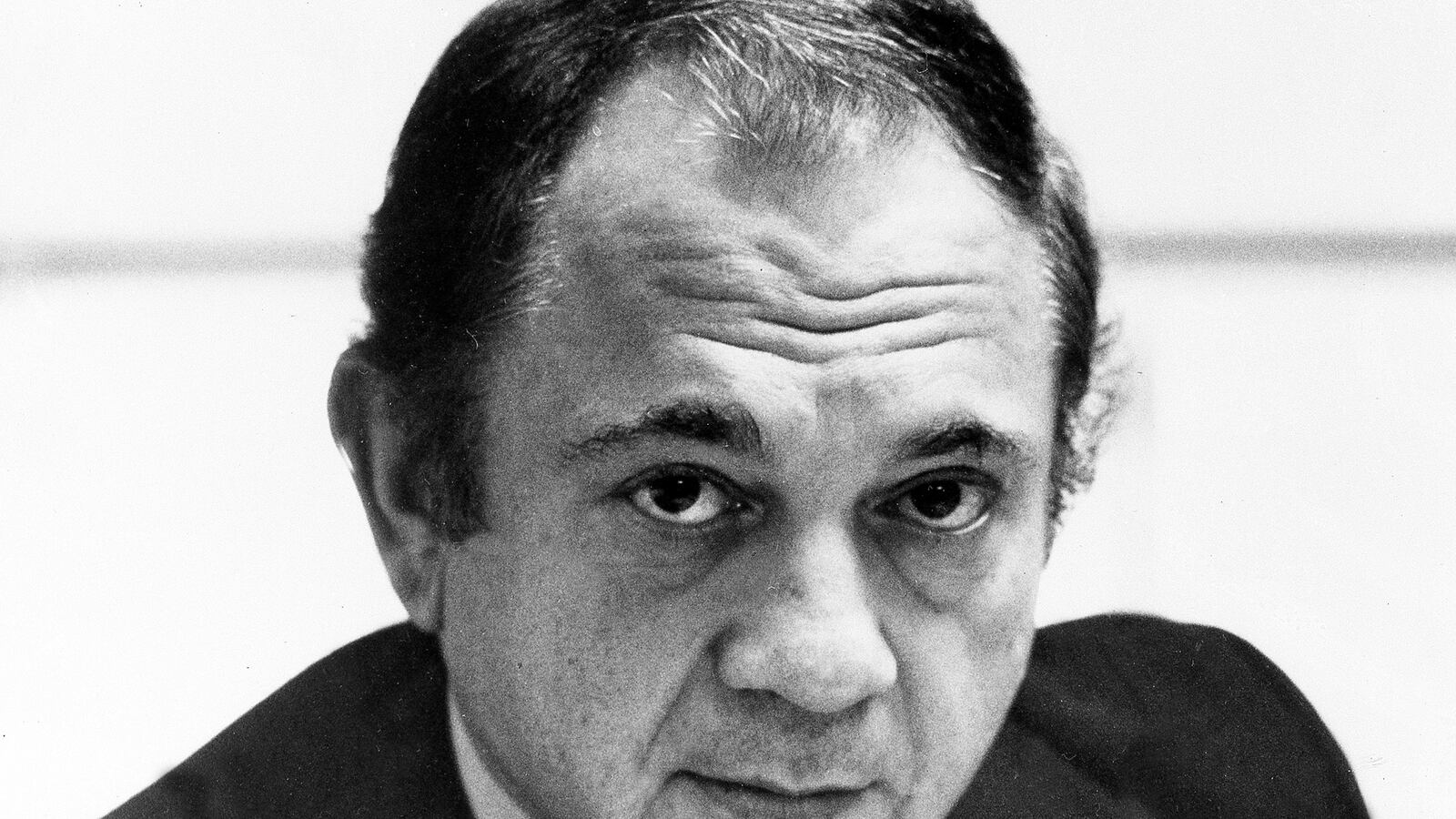

If you worked in the world of New York City politics from the 1960s to the early 21st century, you knew the political consultant David Garth as a kingmaker, a passionate political combatant who combined a skillful use of television and finely honed political instincts to dominate Gotham like no one else. He was a key player in the elections of four mayors: John Lindsay, Ed Koch, Rudy Giuliani, and Michael Bloomberg—who combined to occupy City Hall for 40 out of 48 years. If your beat was national politics, you knew that his roster of campaigns stretched beyond the city, from the governors’ offices in New York State, New Jersey, Connecticut, and Ohio, to Senate seats in Pennsylvania, Illinois, and California, and beyond America’s borders to Israel and Venezuela.

If you were a journalist, you knew that a conversation with David Garth in the midst of a campaign cycle was roughly equivalent to dealing with a Marine drill instructor having a very bad day. Phone lines would catch fire from the velocity and ferocity of his words. In the seven years I worked for him, I often was tempted to follow up Garth’s frank and open exchange of views with a reassuring call to a shaken reporter. “No, no, of course he doesn’t know where your kids go to school.”

It was this side of Garth that was captured on celluloid in the person of Alan Garfield in the 1972 film The Candidate, where the cigar-smoking, blunt=talking consultant explains to the innocent would-be senator how his youth might convince the voters that his elderly opponent “can’t get it up anymore.”

So it’s tempting to see Garth, who died Monday at 84 after years of declining health, as a colorful political player from another time. It would also be a serious misreading of what he brought to political combat: strategies and tactics that are in depressingly short supply today. At root, Garth’s fundamental premise was faith in the voter’s willingness to absorb a political argument—even in the context of a 30- or 60-second spot.

His ads were often packed with facts and figures: here are the laws I helped to pass; here’s how many jobs I helped create; here’s how bad the economy has gotten in my opponent’s years in office. Clients often complained that viewers couldn’t possibly digest all those facts. Garth would patiently—okay, impatiently—explain that the commercials would be seen repeatedly, so the more information, the less likely it would be that bored viewers would turn away.

He also believed, as a matter of political prudence, that the commercials had to be defensible on matters of fact. One of the key staffers in his office, Maureen Connelly, was charged with vetting the commercials. If she felt the ads were false, or even misleading, she had effective veto power; not out of high-minded nobility, but as a kind of insurance.

Because Garth was at heart a political thinker, rather than a media-centric operative, the ads grew from his sense of what a campaign’s central message had to be, and messages contained in political slogans of uncommon length.

When Tom Bradley was trying to unseat Los Angeles Mayor Sam Yorty—a constant contender for other offices—Bradley’s ads said: “Isn’t it about time we had a mayor who wanted to be mayor? Vote for Tom Bradley—he’ll work as hard for his paycheck as you do for yours.” When Ed Koch, a balding, unprepossessing congressman ran for mayor of New York in 1977, his ads read: “After eight years of charisma [meaning John Lindsay] and four years of the clubhouse [meaning Abe Beame] , why not try competence?” And in the Watergate year of 1974, the ads for Rep. Hugh Carey, running in the New York Governor’s primary against the consensus choice of regulars and reformers, urged: “This year, before they tell you what they want to do, make them show you what they’ve done.”

Where Garth’s approach would be most valuable today, however, is his belief that a campaign could make a case that went beyond the most simplistic of appeals. For many political veterans, the most notable example was when Lindsay, a beleaguered incumbent running for re-election in 1969, conceded that he’d made mistakes—something rarely if ever seen in politics. In fact, he acknowledged that he’d guessed wrong about the weather before a snowstorm, and asserted that he and lots of others had made mistakes during a bitter school strike—but it was the idea of an incumbent admitting any error at all that counted.

For me, the most striking example came in Los Angeles in 1973. Four years earlier, Tom Bradley had lost his effort to become the city’s first black mayor. His advisers in that first race counseled had counseled him to avoid the question of race; an issue that Mayor Yorty was happy to seize on with a vengeance.

So in 1973, Bradley went before the camera and said this:

“The last time I ran for Mayor I lost. May some of you worried that I’d favor one group over another. But I couldn’t win that way, because Los Angeles has the smallest black population of any big city in America.”

He went on to say that he wouldn’t want to win that way—but it was the blunt acknowledgement of racial concerns, and an almost shocking willingness to talk about black and white political power in the context of a campaign ad, that is still striking 40-plus years on.

Today’s political media mavens appear to have little or no faith in their ability to convey a tough, even unsettling message in the confined space of a TV commercial. I think they could learn something from their pioneering forebear. Can’t talk clearly about income inequality, climate change, immigration, torture, Wall Street behavior? “The hell you can’t,” he’d say, jabbing with his cigar at the current crop of consultants: adding: (adjectives deleted): “If there’s a ——ing elephant in the room, tell them you see the ——ing elephant in the room, and here’s how you’re going to deal with it.”