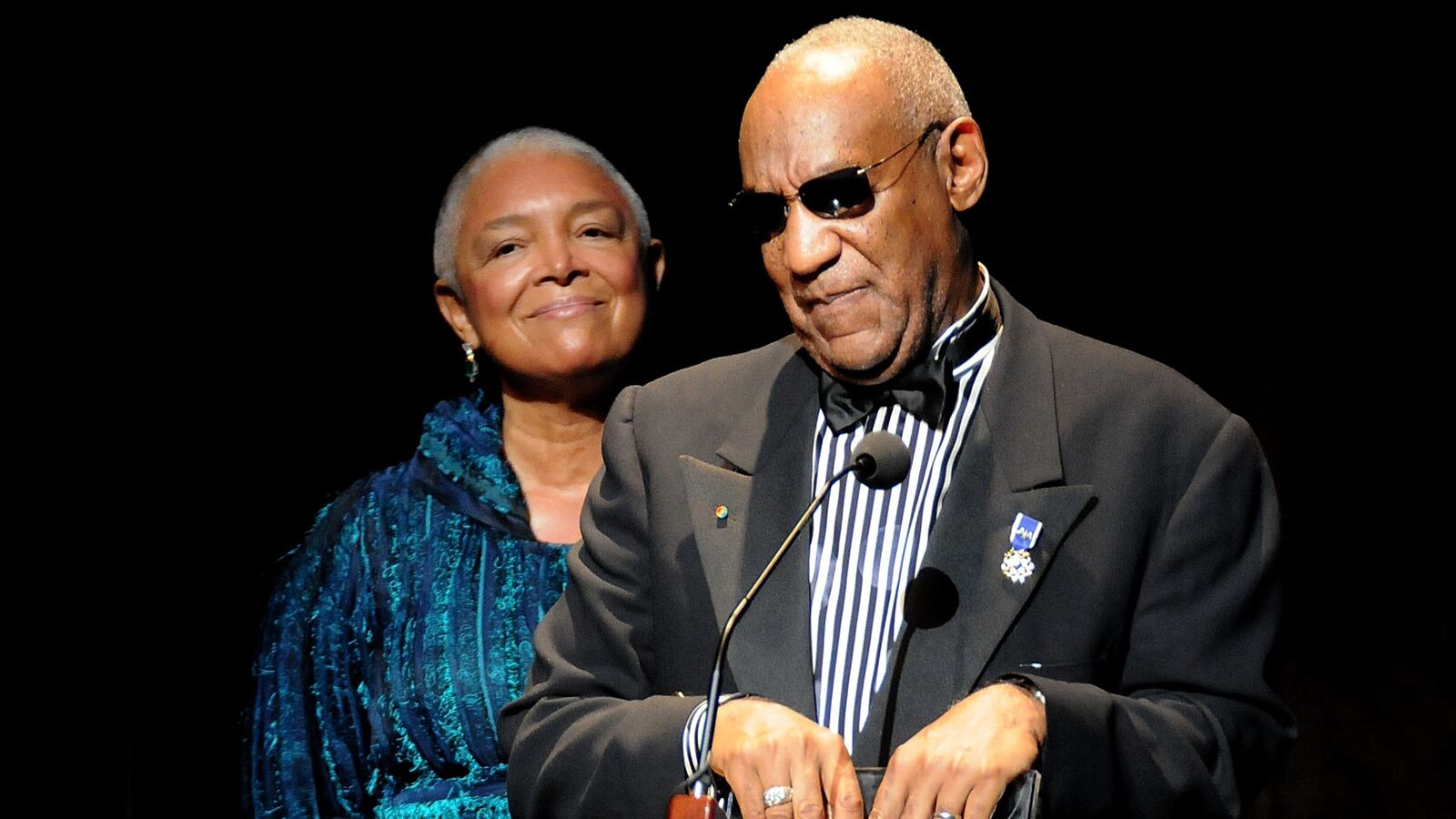

As the number of women accusing Bill Cosby of sexual assault and other misbehavior grows dizzyingly high, it is becoming increasingly hard for all but the most devoted rape denialist to wave the accusations away as baseless. It’s also been hard for many, particularly women, not to wonder how Cosby’s wife, Camille Cosby, must be reacting to this. Many women like to think that if they were in her shoes, they’d be throwing the bastard on his ass with one hand while calling their divorce lawyer with another, a pleasing fantasy of righteous anger unleashed.

Camille Cosby didn’t do that. Instead, she released an incredibly manipulative statement trying to link Rolling Stone’s questionable story about rape at UVA to the stories about her husband, even though the two situations have nothing to do with each other. She complained that there “appears to be no vetting of my husband’s accusers,” an accusation that falls flat when you look at how thorough much of the reporting has been on this.

“None of us will ever want to be in the position of attacking a victim. But the question should be asked—who is the victim?” she concludes, clearly hoping you think the answer is “Bill Cosby.”

Why is Camille Cosby going on the record and not Bill Cosby? Ironically, this kind of move is intended to exploit the public’s belief that the typical woman would immediately leave a bad man. “I would leave my husband if he did such a thing,” they’re hoping you think, “and so, if she forgives him, it must be because he’s not guilty after all.”

Seeing a woman forgive where we expect to see a woman sharpening her blade of vengeance is the go-to tactic in public relations for just this reason. That’s why the wife is dragged out in front of the cameras to publicly forgive the errant husband both in cases of ordinary infidelity (Elliot Spitzer, David Vitter) and in more serious cases of violence against women (Ray Rice).

Publicly standing by your man after he’s been hit with serious allegations of sexual abuse is even a sub-genre of its own. Anne Sinclair, wife of the head of the IMF Dominque Strauss-Kahn, made a big public show of standing by him after he was accused of rape. (She has since divorced him.) Jerry Sandusky’s wife, Dottie Sandusky, continues to deny the overwhelming evidence that her husband is a serial child molester. Even Kenneth Moreno, the NYPD officer who barely escaped charges of raping a woman while on duty but was definitely found guilty of official misconduct and fired, got to enjoy having his wife Julia Moreno blame the alleged victim instead of her husband, even though he was caught on tape admitting the sex happened. Fired cops and imprisoned ex-coaches aren’t exactly moneybags, suggesting that the old excuse, that they’re doing it for the money, doesn’t fly.

In fact, when you tally it, it becomes clear that the norm is not for women to up and leave in a fiery rage after their man has done them wrong, but instead to stay and make excuses for him. So much so that it was actually startling to see Jenny Sanford, wife of then-South Carolina governor Mark Sanford, refuse to stand with him at his adultery admission press conference. But most women do the walk with their man, even if they later wise up and decide to leave him after all. Why is that?

A big part of the reason is a simple psychological phenomenon called cognitive dissonance. “Cognitive dissonance is a state of tension that occurs whenever a person holds two cognitions (ideas, attitudes, beliefs, opinions) that are psychologically inconsistent,” write psychologists Carol Tavris and Elliot Aronson in their book Mistakes Were Made (But Not By Me): Why We Justify Foolish Beliefs, Bad Decisions, and Hurtful Acts, “such as ‘Smoking is a dumb thing to do because it could kill me’ and ‘I smoke two packs a day.’” Or, in this case, between “this is the man that I, a good person, chose to love” and information suggesting he isn’t worthy of your love.

We all suffer from cognitive dissonance and we are all capable of coming up with “ingenious, self-deluding ways,” according to Tavris and Aronson. And once we make a decision—to take a job, to enter a marriage, to get a pet—we start coming up with reasons to justify that decision while minimizing reasons to regret it. We focus on our lover’s delightful laugh and ignore the way he picks his teeth at dinner. We coo over how cute our cat is and minimize the drudgery of cleaning the litter box.

Most of the time, this strategy of resolving cognitive dissonance by justifying decisions we’ve already made is a good thing—without it, we’d always be paralyzed with wondering “what if” we took another job, lived in another city, or married someone else. But unfortunately, the same psychological mechanism that keeps you from second-guessing ordinary, perfectly good decisions leads you to justifying objectively bad decisions in exactly the same way. In the book, Tavris and Aronson argue that the same ability to overlook minor flaws in a marriage leads to overlooking major ones. “To avoid facing the devastating possible that they invested so many years, so much energy, so many arguments,” they write, people will latch on to any excuse they can to stick with it.

When I spoke to Tavris about this phenomenon, she emphasized that everyone does this. “Women are just like men who stay in a bad deal, a bad job, a bad love affair, a bad war and justify that decision,” Tavris explained. Leaving may be hard because it means having your heart broken, losing a life you built, or even going through the stress of divorce, so many women stay. “And once a woman decides to stay,” Tavris explained, “she will emphasize the reasons to stay and minimize the importance of the reasons to leave.”

With women put in front of the public to justify staying with bad men, we see these justifications in full bloom. Camille Cosby hints that it’s a conspiracy against her husband. Janay Rice emphasizes the counseling and her husband’s stated regret. Julia Moreno argued that her husband’s alleged victim is the bad guy here. Dottie Sandusky says that her husband is innocent.

But even though doubling down after we realize we’ve made a terrible mistake is just human nature, that doesn’t mean we have to give up hope. Sometimes people resolve cognitive dissonance by quitting smoking, divorcing the bad guy, or selling the crappy house. Ironically, the same psychological crutch of self-justification can then help in these situations. Once you decide to leave a bad marriage, for instance, you will immediately start coming up with reasons to justify why this is a good decision: You start focusing on how fun dating will be, you get excited about having an apartment of your own, you think about what sex with someone new will be like. But first you have to overcome that natural human urge to keep throwing good money after bad, and that is a difficult task for most of us.