The protests and pain over the deaths of Eric Garner and Michael Brown had me wondering if we can ever experience the world as others do. For no matter how disputed the circumstances of both cases, many people see what happened in black and white. They believe that these two people died because of a racism that permeates our society.

I recognize my inability to truly understand these events in the same context or view these events through exactly the same prism. For me, building that understanding comes through learning and listening, which underpin my work as a journalist and my work pushing for educational justice.

So I turned to a man who has spent his life fighting inequity in our criminal justice system and public schools, Dr. Howard Fuller.

Fuller is one of the wisest people I know. A former superintendent of Milwaukee schools, he is now a Distinguished Professor of Education at Marquette University. He is also the founder and director of the university’s Institute for the Transformation of Learning. He has worked tireless through his Black Alliance for Educational Option to help black children gain access to high-quality education.

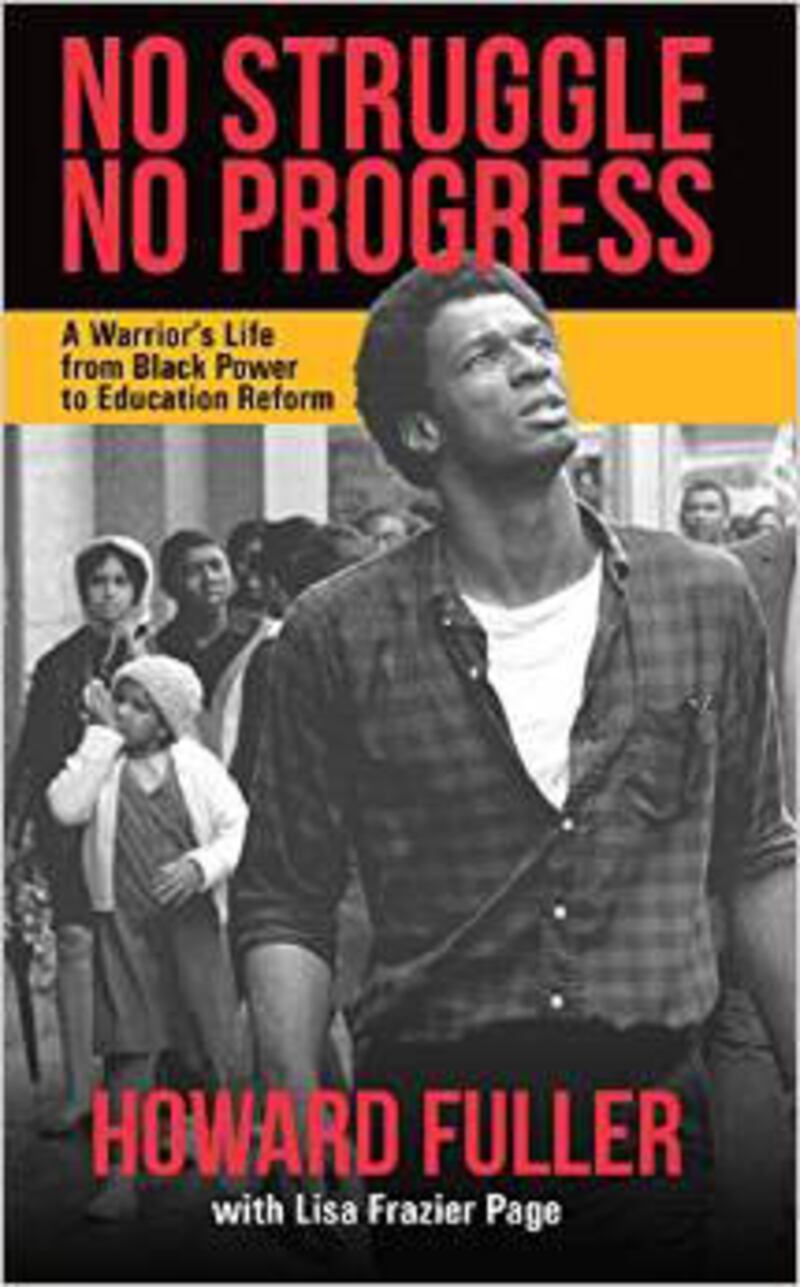

His new book, “No Struggle, No Progress,” prompted me to ask him for help in putting the recent events into context, particularly in the role our schools can play in fixing such a systemic problem. Our conversation follows here, edited for brevity.

Most black Americans think race was a major factor in the deaths of Garner and Brown, and most whites do not, according to Pew Research polling. How do you explain that?Over the years, there have been various incidents where you see this racial dichotomy in the thinking of white America and black America. It just reflects on a very different reality. In spite of all the progress that has been made—and there’s clearly been progress made on race relations—the divide has never been closed, in terms of how black people see what’s happening in this country and how white people see it. And so given the lives that we lead and what has happened both contemporarily and historically, you’ll continue to get this divide.

Isn’t part of what makes that dichotomy so difficult to understand is that we have a black president, and we are evaluating progress in that context?While that represents progress at one level, it has no real impact on the day-to-day lives of the people we’re talking about. It has zero impact. … I never thought personally that I would live to see a black person or a biracial person elected president. But once he was elected, I never thought he was going to have a significant impact on what we’re talking about—in the same way I realized as school superintendent there was a limited impact I could have on the things I saw. And that’s a difficult thing to come to grips with.

The Pew poll also found most African Americans expect relations between police and minorities will actually get worse. Can you address that pessimism?It’s not like there’s no material basis for this pessimism. It’s because you continue to see this happening over and over and over again.

What role can schools play?Schools are extremely important to create the possibility for individual lives to be better. And the hope is that if you can change their individual lives, it will have an impact on their families. It is a life raft for those kids. When I started out, I actually thought I could change the world. I really did.

You don’t believe that anymore?Not in the same way. … I now feel like what I’m on is a rescue mission. And what I’m trying to do is rescue as many kids as I can. … As I say to people all the time, you don’t know what saving the life of that one kid is going to mean to the world. And I think we’re all carrying that hope around that these kids we make a difference for, that they’re going to have an impact on the world.

Can you chip away at the distrust of the police among black people?You know, hopefully. My pessimism doesn’t frustrate me to the point that I’m not going to get out and continue to fight. My pessimism leads me to fight harder, or try to understand how I can do it differently.

Are you more pessimistic about the overall public education crisis given this current environment?The question is, do we have the political environment that will allow the level of change that we need to really make a significant difference? And unfortunately, I would say right now, we don’t.

Why? Because we lack real bold leadership?Yes, and it can’t just be driven by what the polls say. … The kinds of things that you’re working on, Campbell, the kinds of things that I’m working on, you have to push through them, in spite of the political dynamic it creates. Because not only is it right; it’s absolutely clear that as long as these things stay in place, the level and types of change that we need are not going to happen.

How do you talk to children about Garner and Ferguson?It partly depends on their questions. The way that I’ve tried to raise my children, for better or for worse, is there’s a part of me telling them stuff, and there’s a part of me listening. And I think if we’re not prepared to listen, the telling part is going to be less effective.

Is education a civil rights issue?I never used that terminology. When I look at the education reform effort, I see an effort to do what (Brazilian educator) Paulo Freire said, and that was to make sure that people are able to engage in the practice of freedom. Which means the transformation of their world. And I would like for this generation to define its own movement.