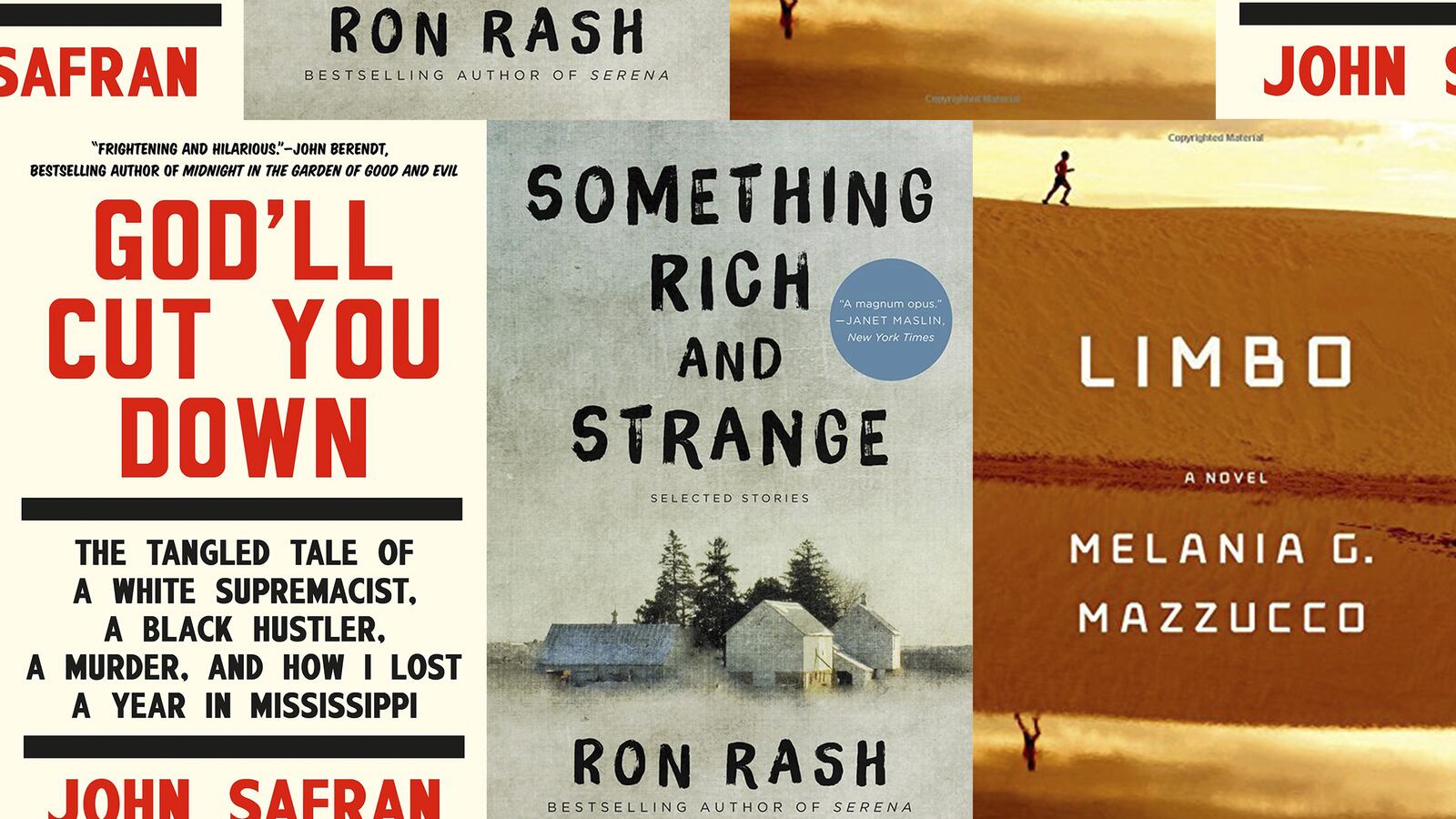

God’ll Cut You Downby John Safran

In 2010, the career of Mississippi white supremacist Richard Barrett came to an abrupt end when he was found stabbed in his home, his body badly burned. Halfway around the world, news of Barrett’s death piqued the interest of John Safran, an Australian broadcaster and provocateur who usually covers race and religion. For one episode of his television show Race Relations, Safran donated sperm to a Palestinian sperm bank (Safran is Jewish). On another occasion, he attended a rally organized by white supremacists and took the podium to announce that a surreptitious genetic test had proven that the organization’s leader—Barrett himself—had African ancestry.

Returning to Mississippi to cover Barrett’s murder, Safran sets his ambitions a notch higher: he’ll write a true crime classic exposing the South’s bigotry for once and for all. But he is altogether unprepared for the case’s complexity—and, for that matter, the complexity of Barrett’s killer, Vincent McGee. A volatile young man with multiple tattoos on his face, McGee is the product of a dysfunctional family and a survivor of childhood abuse. More troublingly for Safran, McGee claims he had no idea Barrett was racist. “I wanted the narrative to be me and the brave McGee family against ‘the system.’ I wanted to be hanging with the black activist lawyers, but they’ve cut me off. Worse, I got on smashingly with Jim, the white supremacist [an acquaintance of Barrett’s]. This story isn’t working out like it should,” Safran writes.

The hardest part of the story to unravel is just what prompted McGee, who had been hired to do occasional yardwork for Barrett, to attack his employer with a kitchen knife. Was it an act of self-defense? Was it retaliation for a sexual advance? Was it part of a dispute over money? Finally, what exactly was the nature of Barrett and McGee’s work agreement in the first place? Safran’s perspective as a comedian and outsider has its advantages: No one in Mississippi knows quite what to make of him, and his candid, self-deprecating take as someone who is a complete foreigner to his material is frequently refreshing. Too often, though, Safran’s ignorance of American history and his eagerness to fit the story to his preconceived expectations get in the way of his reporting. Most troubling are Safran’s investigative methods. When McGee repeatedly demands hundreds of dollars be loaded on a prepaid debit card as the price for his conversation, Safran again and again complies. At McGee’s behest, Safran even picks out, pays for, and delivers a WalMart engagement ring to McGee’s girlfriend (while suggesting she distance herself from him). Still, McGee never trusts him enough to tell the complete story of what happened that day. “If I find out you’re the conspiracy, you’re trying to trap me or something, I’m gonna knock your noodle,” McGee says. And who really can blame him for that?

Something Rich and Strange: Selected Storiesby Ron Rash

There’s something slow, deep, and bewitching about Ron Rash’s new anthology of short stories—certainly “Something Rich and Strange,” too, as the title suggests, but above all, it’s the steady dark undercurrent of hard-earned wisdom that unites and finally defines each of these powerful tales.

Rash’s characters have deep ties to the North Carolina Blue Ridge mountains: They are born on them and die on them and in the interim, live by them, as in “Into the Gorge,” where the pull of tradition leads a 68-year-old homestead owner into a violent confrontation with a U.S. Park Ranger over illegal ginseng harvesting. “Old age was supposed to give a person dignity, respect,” he thinks; the disorienting change it brings instead (new opaque rules, young unfamiliar rangers), seems un-poetic, if not unjust. It’s not that Rash’s characters are incapable of adaptation; even in retirement, the veterinarian of “Three A.M. and the Stars Were Out” has found a peaceful way to practice his line of work and commune with his neighbors. It’s just that the world around them is slowly but surely falling apart.

Methamphetamine addiction is central to more than one story. “They were getting more imaginative,” a pawn shop owner thinks of his addict customers in “Back of Beyond.” In the even more tragic story “The Ascent,” a young boy suffers dearly for his parents’ meth habit. Whether because of addiction or the leanness of the economy itself, heartbreakingly, there’s never enough money for the men and women in the pages of this volume to get by. In the opening story, “Hard Times,” two neighboring families struggle to retain the threads of their dignity in the face of the Great Depression’s overwhelming deprivation. When everyone is struggling, how much is to be offered to the more destitute, and how much is to be accepted? It’s a theme echoed in “Blackberries in June,” in which the good fortune of a young bride and her husband stands in sharp contrast to the fate of her brother and his family. Looking at her sister-in-law, Jamie sees “something she recognized in every older woman in her family. It was how they looked out at the world, their eyes resigned to bad times and trouble.” Or as her mother tells her, sternly, “You got to accept that life is full of disappointments.” It’s a marvel that Rash has crafted stories so fulfilling out of so many of these disappointments. Much like Jamie, he acknowledges—but will not capitulate to—the circumscribed world they create.

Limbo: A Novelby Melania G. Mazzucco, translated from the Italian by Virginia Jewiss

When Manuela Paris returns to her seaside hometown of Ladispoli, Italy from her tour as a platoon commander in Afghanistan, “everyone wants to see her.” Her sister Vanessa tells the TV reporter it’s not like her sister to bask in the public’s attention, though, because “she hates pretentiousness and would never want people to think of her as a hero, or a victim—she was just doing her job, like when a bricklayer falls off scaffolding, or a factory worker gets splashed by acid. She chose that life, she knew the risks, and she didn’t let the difficulties get to her, that’s why I think it makes sense to talk about Manuela Paris, because young Italian women today aren’t all bimbos with no brains or values who only think about money, they’re also people like my sister, who have dreams and ideals, and the courage to try and fulfill them.” In fact, nothing could sum up Manuela better.

Italian novelist Melania Mazzuco’s previous work has won worldwide recognition; Limbo is her second novel to be translated into English. Alternating Manuela’s first-person recollections of war with the story of her readjustment to life in Ladispoli, Limbo is an unconventional exploration of the toll of war—and its aftermath—on its combatants. Just doing her job, as Vanessa says, has left Manuela with the emotional scars of warfare— “avoidance” as her psychiatrist calls it, or, simply PTSD. That’s in addition to physical injuries for which she still needs crutches. In the sections of the novel narrated on the frontlines, Manuela grapples daily with her commitment to the war and her authority as a female leading male soldiers. But back in Ladispoli, she goes through her days in a daze, particularly as she falls into a strange (“frivolous, immoral, deplorable,” she chides herself) affair with a mysterious man named Mattia.

Limbo’s efforts to weave the struggles of a soldier with surreal love story—as well as the story of the kind of ordinary but deep love that binds sisters through life and soldiers on the battlefield—are admirable, even if they fail to fully cohere. What’s remarkable about Limbo, though, is the dreaminess it brings to a story of war’s brutality and the defiance with which it upends the conventions that have come to define the war stories of our time.