Martin Luther King Jr., Nelson Mandela, Oskar Schindler—these names come readily to mind when we think of heroes of conscience. But few of us would recognize the name of Dietrich von Hildebrand, a German philosopher-turned-outspoken Nazi antagonist.

Despite having been described by the Nazi ambassador in Vienna as “the worst obstacle to German National Socialism in Austria,” Hildebrand remains virtually unknown today, even to historians of the period. This makes the recent publication of his memoirs and writings against Nazism—entitled My Battle Against Hitler—all the more momentous. It is not often that we discover a “new” hero destined to count among the greatest figures in the previous century’s fearful struggles against tyranny and genocide.

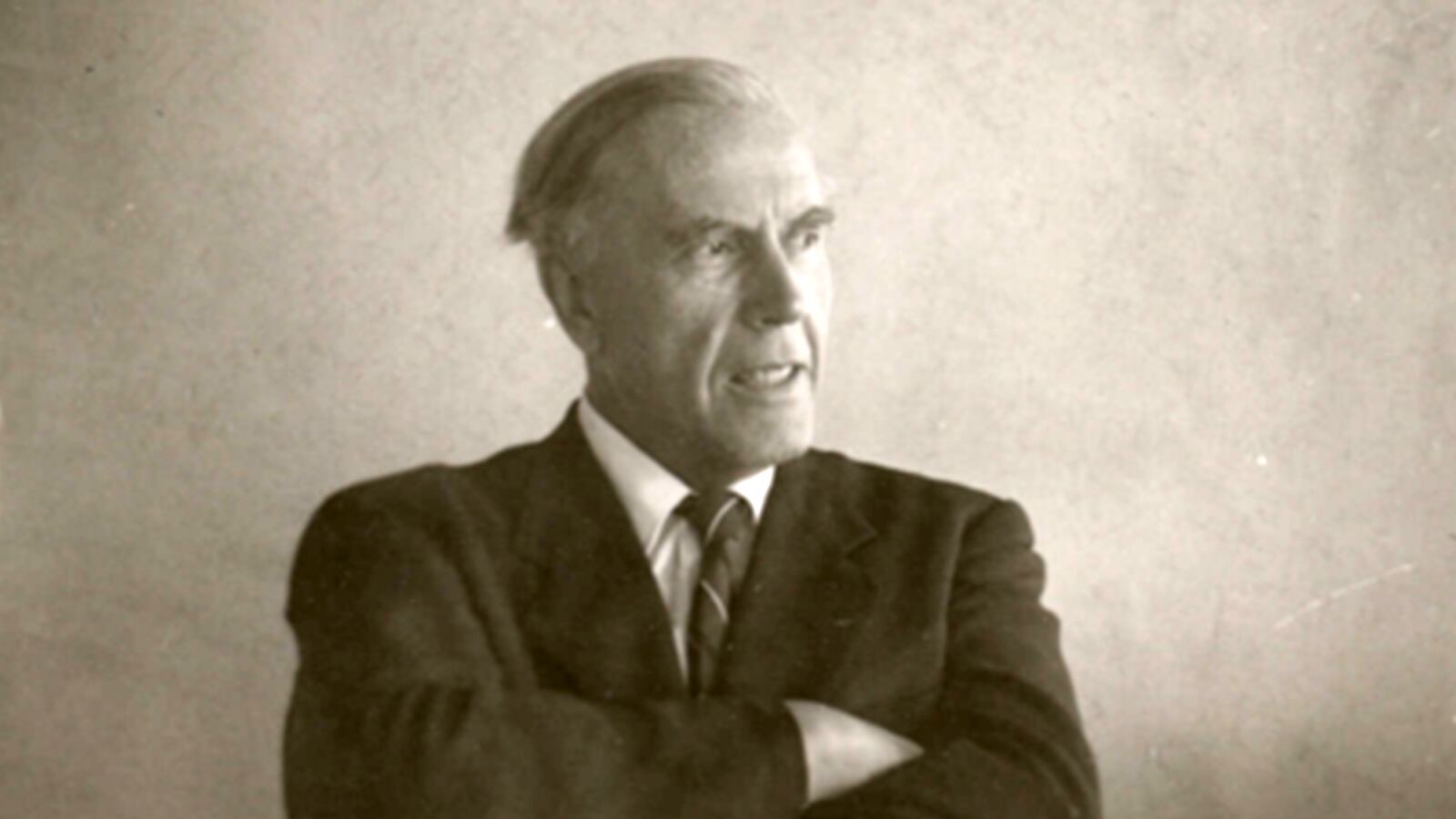

Dietrich von Hildebrand was born 1889 in Florence. The only son of the renowned German sculptor, Adolf von Hildebrand, he grew up in one of Munich’s great artistic families. As a teenager he fell in love with philosophy, which he went on to study under some of Germany’s leading minds, notably the philosophers Max Scheler and Edmund Husserl, who remarked that he had “inherited his father’s artistic genius as a philosophical genius.”

One would be hard-pressed to find an earlier opponent of the Nazis than Dietrich von Hildebrand. Already in 1921—12 years before Hitler came to power—his public denunciations of German nationalism and militarism led the nascent Nazi Party to blacklist him. The risk to his life was great enough that he had to flee Munich when Hitler attempted to seize power in November 1923.

While Hildebrand openly confronted Nazi racism, it is sobering to see in his memoirs that many of his energies were directed at combatting the comparably “soft” anti-Semitism that he found all around him. This was not the racism of concentration camps and gas chambers, but a deep-seated antipathy toward Jews and their purported moral and spiritual degeneracy. While many leading thinkers in Germany—and in America, too, it should be noted—were taken in by pseudo-scientific racial theories, Hildebrand saw in anti-Semitism more than just the hatred of a particular people. “The current attack on the Jews,” he wrote in a 1937 essay, “targets not just this people of 15 million but mankind as such.”

We would miss a certain achievement in Hildebrand’s enmity toward racism and nationalism if we saw them just as acts of courage in the face of manifest evil. What sets him apart from so many of his contemporaries was his rare immunity from the influence of prevailing ideas. We cannot read his memoirs without opening ourselves to the possibility that many of us, had we lived at that time, would have been seduced by the siren song of National Socialism, falling into some compromise or other, and without marveling at Hildebrand’s almost preternatural independence of spirit in his unmasking of Hitler.

When Hitler became chancellor on Jan. 30, 1933, Hildebrand was confronted with a choice: Would he remain in Nazi Germany? By the end of February, as Hitler consolidated his power, his decision was made: He would not—indeed, could not—remain. It is true that he had to consider his safety, for by 1933 he was a well-known enemy of the Nazis, but he left principally in the conviction that he had to speak openly against Nazism, and that he could only do so from outside the Third Reich.

When Hildebrand left Germany on March 12, 1933, he abandoned everything that was dear to him: friends and family members, his rising career, his home. “I expressly made a conscious farewell to the beloved house, indeed to every single room,” he wrote of leaving the magnificent home he had inherited from his father. “It was clear to me that I was unlikely ever to see it again.” But while his departure was “inexpressibly painful,” he never succumbed to bitterness. “Better to be a beggar in freedom,” he cried out, “than to be forced into compromises against my conscience.”

It would take many trying months to discern his future. In the spring of 1933, few perceived Nazism with the gravity he did. Finally the pieces came together. Approaching the young Austrian chancellor, Engelbert Dollfuss, whom he perceived as the only European head of state openly opposing Hitler, Hildebrand offered himself as an “intellectual officer.” Dollfuss was impressed and agreed to finance a new anti-Nazi newspaper to be published under Hildebrand’s editorship. In the pages of his paper, Hildebrand would publish some 67 essays forcefully taking on Nazi ideology in the public square and rallying many troops to his cause.

From the moment of his arrival in the Austrian capital in the fall of 1933, Hildebrand was a controversial figure, attracting both supporters and detractors. He was accused of being extreme, of failing to accept the inevitable, of refusing to cooperate with those who thought they could influence the Nazi regime in a good direction by collaborating with it. None of this deterred him.

Hildebrand’s newspaper had a circulation in the thousands, yet his voice echoed far beyond Austria. Hitler wanted him silenced, the Nazi government repeatedly demanded his paper be suppressed, and Hildebrand on several occasions was warned that plans were being made for assassination. Hildebrand’s voice was even heard in America, as evidenced by a recently discovered FBI memo, apparently signed by J. Edgar Hoover himself, which describes Hildebrand as a “famous foe of Nazism” and the “editor of the most violently anti-Nazi newspaper in Austria.”

Hildebrand would eventually arrive as a refugee in New York City on Christmas Eve 1940, his passage from Portugal via Brazil arranged in part by the French philosopher Jacques Maritain and the Rockefeller Foundation. His harrowing escape from Vienna when Hitler took Austria in March 1938 is dramatically chronicled in his memoirs.

Hildebrand’s courage and clarity naturally awaken our curiosity. What could have sustained him during these darkest of hours? The answer may come as a surprise. Having been raised in a totally non-religious home, Hildebrand converted to Catholicism in 1914. He would remain an ardent and committed Catholic until the day he died in January 1977. Even as he confronted Hitler on the firm basis of philosophical argument, his Christian commitment provided him with both spiritual sustenance and key philosophical categories for his confrontation with the Nazi ideology.

Hildebrand was keenly aware of the grievous failures of Christians under Nazism. Yet he never wavered in his conviction that Christianity was the only spiritual force powerful enough to contend with humanity’s capacity for evil. It was the ultimate guarantor of the humanism he advanced against Nazism. He saw the true antithesis to genocidal and totalitarian ideologies not in vague notions of respect, but in Revelation: “All of the Christian West stands and falls with the words of Genesis,” he writes in one essay, “‘And God created man in His image.’”

It is all too easy to be despondent in the face of what seems like the endless capacity of evil to reinvent itself. But perhaps it is precisely for this reason that the rediscovery of Dietrich von Hildebrand could not come at a better time. For through his words and deeds, he gives us hope that even the most brutal and terrifying forms of evil can be overcome by the moral witness of those who have the courage to stand up to it.