From city to city, bar openings are covered with bated breath, as reviewers judge the authenticity of the latest speakeasy, the grub of a new Irish pub, or tunes playing from the jukebox of a dive. But some places have a history so rich and long, these new and shiny hot spots can only dream of fostering the kind of legendary moments they've played host to.

Christine Sismondo, author of America Walks into a Bar: A Spirited History of Taverns and Saloons, Speakeasies and Grog Shops, spent five years on-and-off traveling the country to track down the most storied of American watering holes.

With her help, we've gathered the ultimate list of the country's greatest influential bars. These still-standing establishments have shaped the course of history and served as the site of some of America's biggest moments—from a tavern where George Washington deliberated on independence from Britain, to the stage of Bob Dylan’s first big break, to the riotous site of the modern gay pride revolution.

City Tavern, Philadelphia

Back in revolutionary times—when taverns not only quenched your thirst, but watered your horses and put you up for the night—John Adams arrived in Philadelphia and went straight to City Tavern, which he dubbed “the most genteel tavern in America.”

It was 1774, and the watering hole, which was used for social and business purposes, ended up being the gathering spot for delegates who’d come to attend the First Continental Congress, a body of representatives from all the colonies (minus Georgia). The attendees, who included John Adams and George Washington, set about forming a plan of governance for the new nation.

As the delegates were deliberating, Paul Revere rode to City Tavern clutching a copy of a document called the Suffolk Resolves to ensure a division from Britain, and that it would be supported by the Congress. A year before he had similarly arrived with news of the Boston Tea Party.

From then on, delegates of the Second Continental Congress would continue to meet every Saturday in the tavern, and some frequented it daily. It was where Thomas Jefferson dined while drafting the Declaration of Independence, and the scene of the very first Fourth of July celebration in 1777.

The structure was partially burned down and then destroyed in the mid-1800s, but was accurately reconstructed more than 100 years later, in time for America’s Bicentennial. Sismondo calls it the “first world-class tavern built” and says the bar’s restoration work has turned the current version into an accurate representation of its storied original.

Cafe Wha?, New York City

With the likes of Bob Dylan, Bruce Springsteen, and Bill Cosby peddling their wares on the legendary stage of Cafe Wha?, it’s no surprise the Greenwich Village bar has taken on a reputation of legendary proportions.

Wha started out in 1950s as a hangout of the Beat generation, until, according to general lore, Dylan got on stage on a winter afternoon in 1961 and performed a few Woodie Guthrie songs. In the years to come, Wha became a legendary starting out spot for various soon-to-be rock stars.

Today, while it’s not the cool-kid music venue it once was, the cafe hasn’t lost all of its star-power. In 2012 Van Halen reunited on its stage, as if just to prove that Wha ties run deep as blood: lead singer David Lee Roth is actually the nephew of Manny Roth, the club’s legendary owner, and has been frequenting the venue since he was a young boy.

The Horse You Came in On Saloon, Baltimore

Horse-themed bars must be bad luck for famous authors. Not unlike New York’s White Horse Tavern, where Dylan Thomas is rumored to have taken his final drink before returning home and dying, The Horse You Came in On in Baltimore claims to be the last known locale frequented by Edgar Allan Poe.

The poet apparently collapsed in the street upon his departure from “The Horse” and died not long after. The pre-Revolutionary bar, which claims to be America’s oldest in continuous operation, is now host to a playful ghost that bartenders have nicknamed “Edgar,” who they placate with a glass of whiskey left on the counter at closing time.

The Green Mill, Chicago

The Green Mill has a history tracing back to 1907, and though it once served Charlie Chaplin, is best known for its Prohibition-era antics. Jack “Machine Gun” McGurn, an employee of Al Capone’s who was suspected of being the leader of the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre, held a quarter stake in the club. While the infamous Capone himself owned a speakeasy hidden across the street, he preferred hanging at the Green Mill, where heavy police bribery meant he could drink above ground and listen to his favorite singer, Joe E. Lewis.

“If one of his gang owned it and he hung out there it would have been really mob central for Chicago, and would have been the place to drink,” Sismondo says. Other musical acts featured the likes of Billie Holiday and Al Jolson, and the bar served as the subject of movies like The Untouchables and Prelude to a Kiss.

Visitors today can keep watch over the scene in the booth at the end of the bar that Capone and his cronies once occupied. Unfortunately, the underground tunnels that were used to transport booze and, if necessary, escaping patrons, are off-limits. But its claims to fame since can’t live up to the Capone days. The bar also claims that it hosted the first-ever poetry slam 28 years ago.

Pinkie Master’s, Savannah

“I guess it’s a really good populist move to declare your presidency at the dive bar,” says Sismondo of the unpretentious, legendary Pinkie Master’s in Georgia. The joint, right next to Savannah’s Hilton hotel, was prime for off-the-record conversations after more formal political gatherings, and its owner, Pinkie himself, was a well-respected and powerful man.

Governor Jimmy Carter apparently announced his presidential candidacy standing on the bar, and it’s theorized that the support Masters threw behind Carter is what carried the district and propelled him to the national stage.

“People really did think it was a political stronghold,” Sismondo says. “When you look at the history of bars in America, they would tell people who to vote for, and they would.” She adds that some of the earliest voting booths were stationed inside drinking establishments. “Union leaders hang out at the bar, and it’s a place where people would consolidate power.”

Later, the bar’s “elders” have said, Al Gore tried to mimic Carter’s strategy to disappointing results.

Carter hasn’t forgotten his humble beginnings. In 2002 the former president eschewed the bartender’s offer of juice or soda for a can of Bud Light.

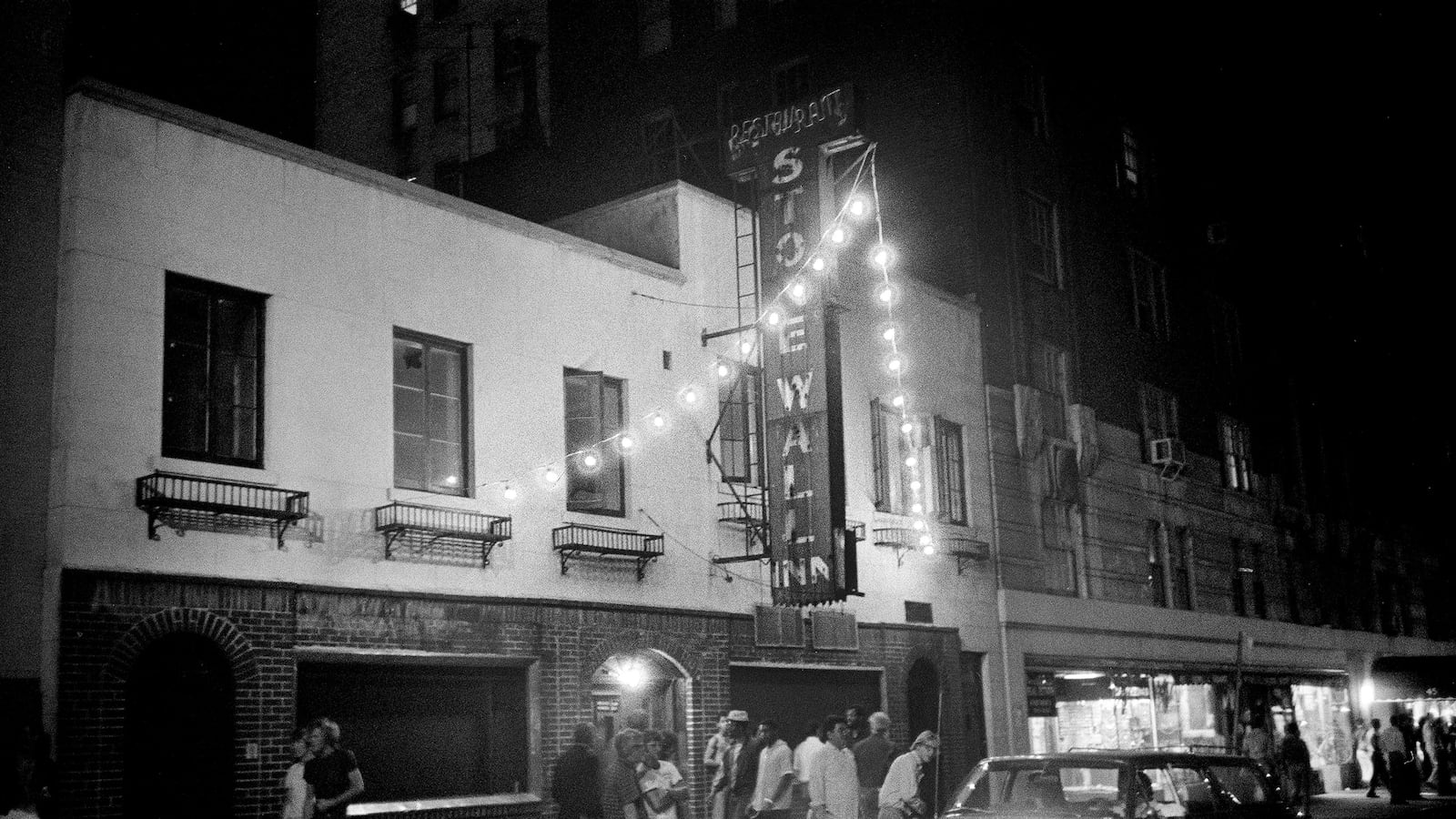

Stonewall Inn, New York City

Few bars are as synonymous with a rights moment than the West Village’s Stonewall Inn, an LGBT bar that still thrives today. In 1969 it was the site of the history-shaping Stonewall Riots, during an era when it was illegal for bars to serve homosexuals.

On a June evening, 200 or so Stonewall patrons rebelling against consistent raids by the NYPD, fought eight police officers who were trying to empty the venue. They overturned a police wagon, destroyed the bar’s innards, and gathered a crowd of more than 600 rioters.

The following week, protesters continued to show up outside the bar, demonstrating for gay and lesbian rights. Though the bar closed soon after, a movement had been sparked, and when it reopened in 1990, history was revived. New York’s annual Gay Pride parade is a commemoration of those early riots, and the bar bears the tagline “Where Pride Began.”

Heinold's First and Last Chance, Oakland (Jack London, Taft)

You can thank Johnny Heinold for your favorite Jack London book. Before his writing days, London used the Oakland establishment to conduct his studies. A sepia photo shows him as a young boy, head in his hands, with a large book open at a bar table. When he turned 17, the saloon’s eponymous proprietor lent London tuition money to attend UC Berkeley.

“That was bar first made him fall in love with bars,” Sismondo says. His later books drew heavily from experiences and people he encountered at the bar, including the cruel captain in The Sea-Wolf. In John Barleycorn, Heinold and his bar are referenced a whooping 17 times.

But Heinhold’s long history doesn’t start and end with London—the bar’s slanting floor was misshapen during the great earthquake of 1906 as the ground beneath it sank, and the clock on the wall is still stuck on the time the disaster struck: 5:18. In those days, “Last Chance” saloons were a popular place for sailors to drink before setting out for near dry counties where alcohol was scarce and Heinhold's had an all-star clientele, attracting President William Howard Taft, Robert Louis Stevenson, and Ambrose Bierce.

McSorley's, New York City

McSorley's, the Manhattan mainstay with only two beer options and a floor of sawdust, is nothing if not traditional. But in 1969, a longstanding practice was challenged—its ban on women.

It actually all started hundreds of miles away at the Hotel Syracuse, when the female friend of activist Karen DeCrow complained that the establishment wouldn’t allow her and her mother to have a drink “unescorted” by a male. After prohibition, states and bars created their own drinking rules, and many barred women at certain times of the day or entirely.

“Business decision meetings don't take place in boardroom, they take place in the bar after,” Sismondo says DeCrow argued. “In order to get women in better jobs you had to get them into places [decisions] were made.”

DeCrow would come to lead a movement against this practice, suing the Hotel Syracuse in 1969 and calling for protests and sit-ins. That same year, Gloria Steinem protested at the Berghoff in Chicago, while in New York, Betty Friedan attempted to go into the Plaza’s legendary Oak Room and Faith Seidenberg picketed outside McSorley's. Other bars changed their ways, but McSorley’s was stubborn. Eventually, DeCrow and Seidenberg filed suit against the East Village mainstay.

Before it was settled, New York State passed an anti-discrimination law in 1970, and they were forced to open their doors a little wider (not happily, Sismondo says). That year, on August 10, the first woman stepped in for a pint.

Absinthe House, New Orleans

Legend has it, Andrew Jackson and infamous pirate Jean Lafitte hashed out a plan for the victory of the battle of New Orleans on the second floor of this saloon, whose building in the heart of the French Quarter dates back to 1806.

“Bars love to tell those stories: ‘So and so drank here, and George Washington slept here,’” Sismondo says. And the Absinthe House has a full list: Other famous imbibers include P.T. Barnum, Oscar Wilde, and General Robert E. Lee. Another pirate-devoted bar, Lafitte’s, was important for the spin-off that was opened when it closed—“The Café Lafitte in Exile,” claims to be the oldest gay bar in North America, and was a hangout for Truman Capote and Tennessee Williams.

Round Robin Bar, Washington DC

Home of the mint julep’s northern introduction and birthplace of political lobbying, as the story goes, this Pennsylvania Avenue hotel bar, tucked away in a corner off the lobby, has been a DC heavyweights’ gathering place since it opened in 1850.

The Willard InterContinental, within which it is situated, has hosted nearly every president since then, and was used as a writing spot for Mark Twain, inspiration for Walt Whitman, and the accommodations of Martin Luther King Jr. when he made his “I Have a Dream” speech.

“[I]ndeed, the Civil War was more or less administered from there,” an Esquire review asserts. Before Abraham Lincoln moved into the White House, he conducted presidential business in the hotel’s lobby.

“Gerald Ford was known for enjoying Budweiser out of longneck bottles,” longtime bartender Jim Hewes recently said, “and President Obama is somewhat partial to a great margarita, and also martinis.”

But what is rumored to have birthed the term “lobbying” was the practice by Ulysses S. Grant to sip brandy in the lobby as politically motivated solicitors vied for his attention.

“Sometimes I think that bar stories are not 100 percent true, but there’s something great in the fact they persist,” Sismondo says. “The reason we all love that story is we know that’s we know that’s probably how things happen in Washington.”

Comstock Saloon, San Francisco

A boxer at the door and a gangster in the basement. These are the defining historical moments of the Andromeda Saloon, which opened in 1907 on the site of the rowdy Billy Goat Saloon run by“Pigeon-Toed Sal,” which was destroyed in the Great Earthquake.

The new establishment was overseen by boxing promoters--who employed world heavyweight boxing champion Jack Dempsey as a bouncer--and poured drinks for the legendary Jack Johnson. Years later, a regular to the bar was the notoriously murderous bank robber Baby Face Nelson, who was introduced to various Prohibition-era underground rum-runners by the bar’s proprietor and bartender.

He was later nabbed by authorities who, according to local lore, found him hiding in the basement of the saloon. The Andromeda would later become the San Francisco Brewing Company, which closed down in 2009, but reopened a year later as the Comstock Saloon, which has remodeled the venue in the spirit of its location at the Barbary Coast, right in the middle of what was San Francisco’s red-light district during the Gold Rush.