Eighty years ago this week, inventor Leonarde Keeler proudly proclaimed his expert testimony before a Wisconsin jury to be “a signal victory for those who believe in scientific crime detection.”

One of the creators of the modern-day polygraph, the man named after Leonardo da Vinci by his father in the hopes that he would do similarly great things, had just presented his findings in the case of Cecil Loniello and Tony Grignano, two young men on trial for the attempted murder of a police officer as they fled the scene of a robbery. The judge in the case had sought out the polygraph because of the technology’s showing at the 1933 World’s Fair police exhibit. Both sides had agreed to allow the test—the defendants saw little to lose and the prosecution was armed with only circumstantial evidence and two untrustworthy witnesses.

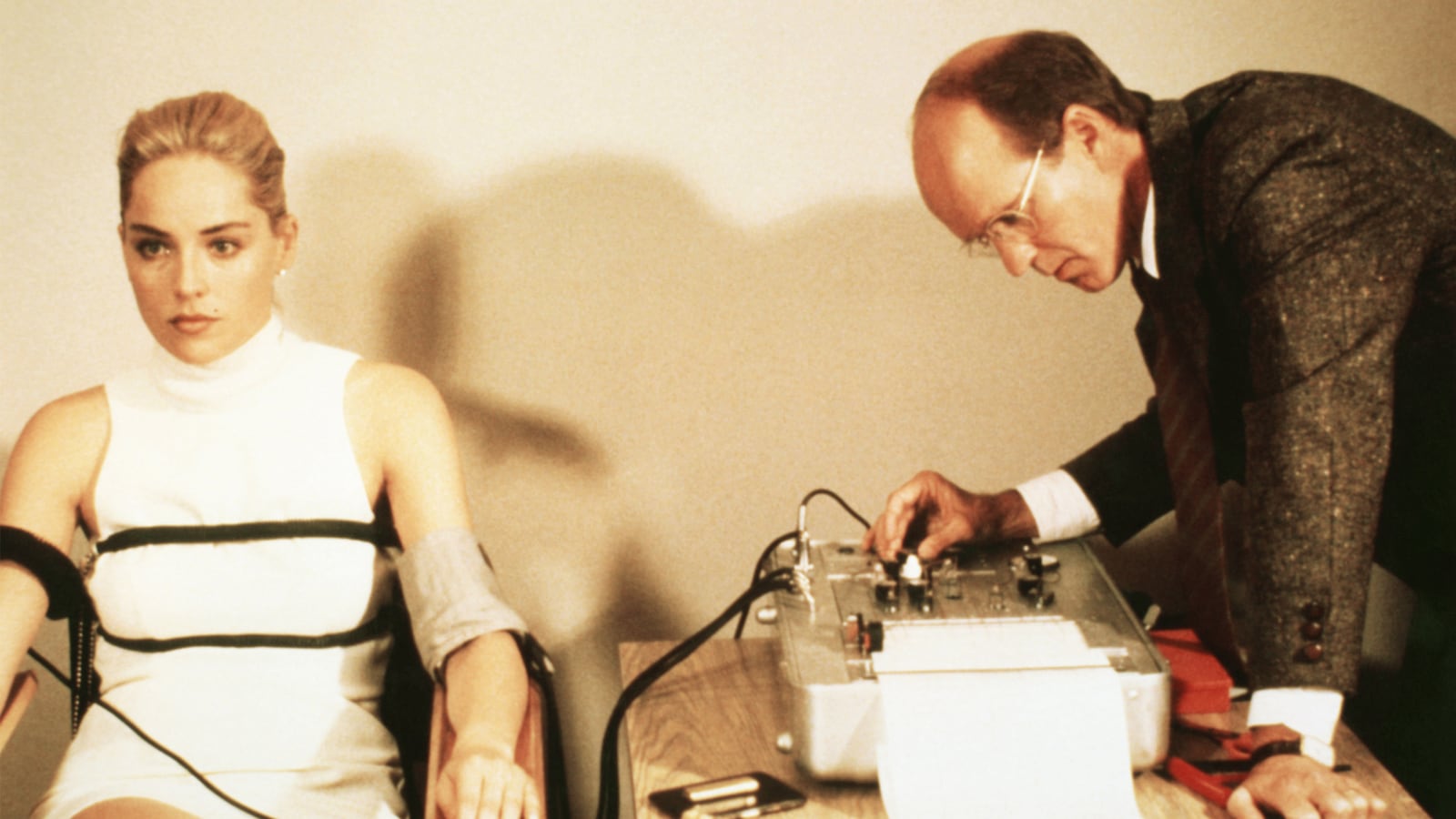

Keeler strapped his lie detector to each man’s chest and arm. When Loniello was asked whether he shot the sheriff, the needle recorded a violent fluctuation indicating a change in breathing, a sudden increase in blood pressure, and a rise in pulse. When asked whether he was driving the car, all systems were normal. The results told Keeler and his colleague, Fred Inbau, not only that the two men were both guilty and lying, but revealed each man’s role in the crime. Science, it seemed, had triumphed.

It was the first time that a jury had been permitted to hear polygraph results as evidence and on the stand Keeler was measured in his statements: “I wouldn’t want to convict a man on the grounds of the records alone,” he told the judge. But outside the courthouse, Keeler beamed when the jury returned with a guilty verdict. “It means that the findings of the lie detector are as acceptable in court as fingerprint testimony,” he told the press.

Except that it didn’t. A previous Supreme Court case had decided a decade earlier that the lie detector hadn’t gained approval from the scientific community and was thus inadmissible in court. Apart from a few rare cases, the polygraph has been barred from federal and most state courts ever since.

“The supplanting of the jury and its judgment are something judges have been very wary of,” said Ken Alder, professor of history at Northwestern University and author of The Lie Detectors: The History of an American Obsession.

As early as 1911, an article in The New York Times imagined this kind of world where a truth box—then called a psychometer—would altogether do away with detectives, attorneys, and juries. “The state will merely submit all suspects in a case to the tests of scientific instruments and as these instruments cannot be made to make mistakes nor tell lies, their evidence will be conclusive of guilt or innocence, and the court will deliver sentence accordingly.”

Despite the wide acceptance of the polygraph today—in police investigations, to monitor people on probation, and by the government to screen potential employees—it may not be used as evidence. But the lie detector has found a more circuitous way into our legal system.

“The results of a lie detector are not admissible in court, but if you confess during the course of interrogation, that’s admissible,” said Alder. “The lie detector is essentially used in practice as a way to get people to confess to crimes.”

Keeler’s polygraph was not the first to be conceived or created. Others were patented by Keeler’s rivals at the time, the most threatening of whom was legendary eccentric William Marston, a Harvard-trained psychologist who would go on to create the Wonder Woman comic (a superhero whose weapon happens to be the Lasso of Truth).

The exact origins of the polygraph go back even further.

“The lie detector pioneers were very keen to stress that it was an invention, like the light bulb,” said Geoff Bunn, a professor of psychology at Manchester Metropolitan University and the author of The Truth Machine: A Social History of the Lie Detector. “In fact, the lie detector that we understand, the polygraph machine, with the three different measurement devices—those were all already in use by 19th-century criminologists. All the lie detector guys did was put them in the same box.”

That box—with its essential tech of sensors that record changes in breathing, blood pressure, and sweat—hasn’t changed much since then. And the problem, Bunn said, remains the same as well: It doesn’t work.

“The basic idea that these [measurements] add up to a lie hasn’t panned out,” Bunn said.

But Keeler’s patented box—among the first designed expressly for police interrogation—did get results. According to unpublished survey data kept in archives, up to 60 percent of the criminals labeled deceptive after an examination with Keeler’s polygraph would confess to their crimes.

Keeler’s intentions, while self-serving (he was a publicity hound who even appeared as himself in the docu-noir film Call Northside 777), weren’t ignoble. He had been good friends with August Vollmer, Berkeley, California’s first police chief and a reformer who looked to the lie detector as an alternative to the brutal interrogation techniques of the time. Soon Keeler moved his operation to Chicago, home to the country’s first forensic lab and a notoriously brutal police force. Keeler’s colleague Fred Inbau later described the Chicago Police Department’s reaction to the polygraph like this: “Why use a polygraph? Beat the hell out of him. If he tells the truth, he’s guilty; if he doesn’t, he’s innocent.”

To be sure, the lie detector was a preferable innovation to the blackjacks and rubber hoses many officers employed at the time. But make no mistake: The truth box just turned intimidation from physical to psychological.

According to Bunn, Keeler would say, “Let them stew overnight in the cell… We’ll hook them up to the sweat box in the morning by which time they’ll be so fearful of it, they will simply confess.”

“It does tend to make people frightened, and it does make people confess, even though it cannot detect a lie,” Bunn said.

Even the lie detector’s harshest critics concede it can be a useful interrogation tool.

“There’s a myth of the lie detector in American society where many people believe it works and that has usefulness in some situations,” said George Maschke, co-founder of AntiPolygraph.org, a website dedicated to cheating and ultimately abolishing the lie detector. “For example if a criminal can be convinced by an examiner he’s been caught in a lie, he might give a confession that can be corroborated by other evidence like the location of a body or details about a murder weapon that only the murderer would know.”

But not all confessions, Maschke notes, are equal. Although, according to the 2,500-member strong American Polygraph Association, professional examiners boast over 90 percent accuracy, virtually every scientific association puts the rate much lower. In 2003 the National Academy of Sciences concluded a century of research in psychology and physiology provides little support for the polygraph’s worth. The position of the American Psychological Association is that the lie detector is more the stuff of TV crime drama than scientific reality.

Statistics aren’t kept on the number of polygraphs administered in criminal investigations and current data on the instrument’s reach is hard to come by. By the 1980s, an estimated one million polygraphs were given each year, over a third by private companies, most of which are no longer allowed to do so after an act from Congress barred the practice.

What’s clear is that misplaced trust in the lie detector has consequences. In some cases people have used widely known methods to cheat: with countermeasures like taking drugs or shocking their senses by biting their tongues or clinching their anuses. In 1987, Gary Ridgway passed a lie detector test by “just relaxing.” It wasn’t until 2001 that advancement in DNA technology pointed to Ridgway as the serial murderer of 48 women.

Even more tragic are the innocent who have been wrongly convicted based on the tests. In October, Jeff Deskovic was awarded $40 million for his wrongful conviction in the rape and murder of a high school classmate. Deskovic was exonerated after serving 16 years, his guilt determined largely on the results of a five-hour polygraph exam in which Deskovic says the examiner called the then-16-year-old a murderer, convinced him that he had failed the polygraph, and left him on the floor in the fetal position to give a false confession.

Even the original polygraph’s most vocal advocates seemingly knew that the lie detector wasn’t strict science. In fact, Keeler would demonstrate the polygraph’s accuracy with a deceptive card trick. Keeler would instruct the subject to pick one of 10 playing cards and return it to the deck—which Keeler marked, just to be sure. The subject would be told to look at the cards individually and deny each was his. The lie would be detected, and the correct card would be chosen, thus, giving Keeler the subject’s physiological “lying response,” but more importantly proving the polygaph’s magic.

“In order for it to work, you have to believe it’s going to work,” Northwestern’s Ken Alder told me. “It was a very clever way to trick people.”