“A quick but powerful and for me painful set of stories about the experience of ordinary soldiers in Iraq,” said President Obama by way of characterizing a contemporary work about the Second Iraq War. Suitability to presidential interest aside, Phil Klay’s story collection Redeployment stands as a daunting feat. Through a series of first-person narrations, it provides a prismatic view of the war’s prosecution and legacy, while giving voice to experiences cloaked stateside in a shroud of unseeing, the sort of memories that pass silently beneath banner and platitude.

If Redeployment has a weakness—and since it’s Klay’s first story collection, it only seems fair it should—it’s in how a certain consistency adheres from speaker to speaker. Klay possesses a keen ear for dialogue, yet his characters generally seem to think in a common manner. A consistency in tenor and form runs from story to story, tendencies a reader might take for Klay’s own habitual mode of expression. (Or else that of the U.S. military altogether—a blinkered judgment, to be sure.)

As if seething from the cracks in the austere façade of fiction like Redeployment, Mark Doten’s debut novel The Infernal arrives with its own array of first-person introspections, each and every speaker obsessed with recounting a view from deep within the machinery of the Global War on Terror. (Which, we shouldn’t need American Sniper to remind us, does not equal the Second Iraq War.) And, no—few traces here of consistency from voice to voice. Teetering along the fine line separating comedy from horror, Doten does the chameleonic with remarkable finesse.

Which is not to say he is concerned only with faithful mimicry. Some voices sound more like themselves than others (Dick Cheney: “I can tell you if we survive this baby we’ve got ourselves one hell of a what do you call it a teachable moment …”) and others are patently shambolic (Karen Hughes: “LOLOLOOLOLO!!!…”), a quality Doten, the author, is upfront about. He says as much in the preface.

Whose voices does his oracle summon? Rather than heroic or haunted everyman, the usual suspects derive in large part from an inversion of that notorious deck of cards handed out on the hunt for Iraq’s fleeing leaders: L. Paul Bremer, Alberto Gonzales, Dick Cheney, Karen Hughes, Roger Ailes, the late Andrew Breitbart (“oink oink” mercilessly is all Doten has for him to say, one more of the novel’s razor-edged jokes).

And more darkhorse still: Jeff Gannon, the White House press corps plant, who, during his brief tenure, lobbed softball questions at the presidential podium, a brand of professional fraudulence that appears now emblematic of the entire Iraq War propaganda apparatus; and Jimmy Wales, the founder of Wikipedia, whose D.I.Y. public encyclopedia exemplifies the fractured state of our media, the vacuum where a Walter Cronkite used to be.

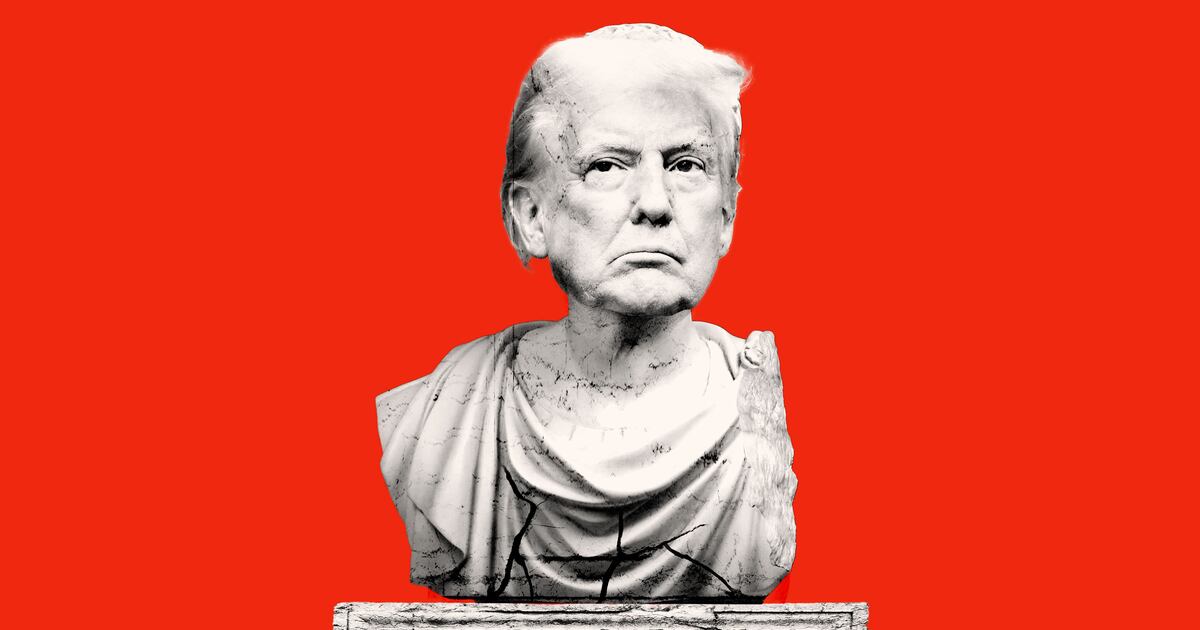

It might seem obvious to link the War on Terror, the errancy of its most regrettable impacts, and Big Data, where every citizen’s keystroke could conceivably be captured for later review—this, in the most paranoid, and yet not entirely implausible, accounting. The void of truth at the front of the train (where are we going? And why?) compensated for by a rapacious (read: evil) interest in what individual passengers think, and how best to sway them in mass: herein falls Doten’s authorial focus. On these grounds he constructs a screaming hysterical novel of protest, the kind rarely seen since the heyday of Thomas Pynchon. (Under questioning, some will aver the heyday of Pynchon continues with only the occasional commercial interruption.) The interplay of evil and power is more than subtext in The Infernal; Doten features himself—along with our sitting president, the reader of fiction, as either an imagined guest or hostage—as characters. Comically, Mark Doten, the narrator, is a major lobbyist on the strength of all his book publishing lucre. Then the monologue turns more disturbing.

Absent by and large is former president George W. Bush, even if a Bush forefather materializes as a key player in the development of the story’s founding conceit. An A.I. database dubbed the Omnosyne, it serves—like that old technology, the novel—to store in perpetuity the ravening voices of the victims and perpetrators of the Global War on Terror. Those, at least, are the voices we receive. In Doten’s telling, the GWOT has begotten an apocalyptic Singularity-like event in which all human consciousness is uploaded to the Omnosyne, all living warmth left behind.

I’ve yet to mention the two Afghani boys who speak in a kind of Ali G patois and escape a drone strike only to encounter an altogether more mundane peril; I’ve yet to mention Noor Khalil, one of the novel’s noticeably few female speakers, a caretaker for the Iraqi war-wounded; I’ve yet to mention Tom Pally, Doten’s American vet in the grip of florid stateside psychosis; I’ve yet to mention the way trauma manifests in The Infernal through surreal imagery or how the text itself looks riven with data corruptions, strings of seemingly meaningless numbers and letters (Enjoy, scholars of tomorrow!); I’ve yet to mention how each monologue contains an obsessive center that transmutes from speaker to speaker in effect linking all these disparate voices beneath a sheltering sky misty with irony right out of Paul Bowles. And … there is still more I’ve yet to mention.

The point is, if you were an aide to the president and saw this title on his desk, it would be judicious to feel some anxiety. “No, Mr. President,” you might say, snapping it up, “No, no—this wasn’t meant for you. I beg your pardon, Mr. President, but this is not for you.” And then what? Open the cover once out of the room? Read a sentence or two? Marvel at the tunnel system Doten has created, a chamber of horrors if ever there was one, walls redounding with laughter of the damned? A Tom Clancy thriller infected with a Barthelme virus and cross-pollinated by an unfinished Kafka doorstopper in correspondence with Edgar Allen Poe, The Infernal means to be representative of the past 15 years, and, in many ways, it is. Nothing comes together at the end. The War on Terror, the prison camp at Guantanamo, the ever-spreading ripples of our invasion, continue with only the occasional commercial interruption.

This is our legacy writ large and scrambled. We are sure as hell in it, whether or not we count ourselves of it.