Internet search engines are marvelously useful for a lot of things.

They can help you find recipes and directions and interesting facts. They’ve rendered obsolete almost all the skills my middle school librarian drilled into my skull decades ago. A quick Google search can tell you who won the Pulitzer for poetry in 1983, or if fate has justly rained down humiliating calamities on deserving ex-boyfriends.

But please, don’t use it to investigate your symptoms.

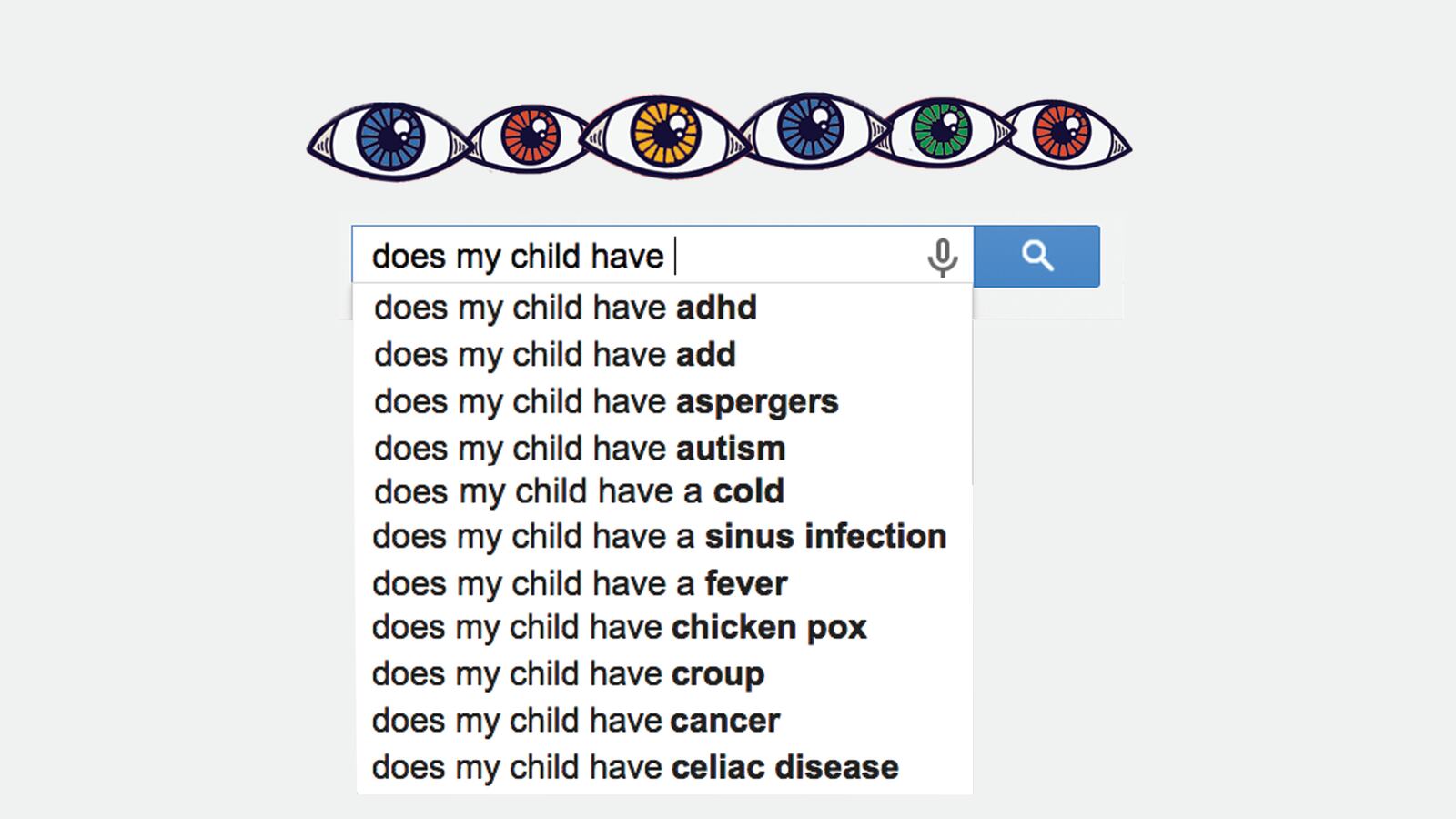

Time and again, parents bring their children in to see me for some relatively straightforward complaint having already hit their web browsers for answers. Unfortunately, the answers they’ve unearthed are invariably dire and anxiety-inducing. Many such parents tell me that they have literally lost sleep over what they’ve read.

I have yet to encounter a circumstance when the catastrophic diagnosis the Internet has suggested has been remotely accurate. Just like all the patients who didn’t have Ebola, none of the grievous ills parents have been driving themselves crazy contemplating have ever been right. While it’s statistically possible that sooner or later I’ll have a patient who really has the horrible rarity Bing (remember Bing?) turned up, I’m willing to bet against it at any given visit.

It’s easy to see how this happens. Typing “skin spot” into my Google search bar, every hit but one boldly proclaims “cancer.” (Oddly, adding the adjective “weird” to the search yields more reasonable results like eczema mixed in with the still-present cancer warnings.) And the top site to mention this diagnosis? WebMD.

When it comes to online sources of medical information, WebMD is the big kahuna. It gets over 100 million unique visits per month, and had over 2.5 billion page views in 2012. Lots and lots of people turn to its “Symptom Checker” for a stab at figuring out what’s wrong with them. And while many of the answers they get may be reasonable, it still turns up a few humdingers.

For example, when I search for causes of a banal symptom like “back pain or discomfort,” the first diagnosis given is a startling “acute kidney failure.” The much more likely “muscle strain” is listed just below it, but the two are given equal weight. (In the absence of other risk factors or symptoms of concern, acute kidney injury would be relatively low on my list of diagnoses to consider for someone with isolated complaints of back pain.) Should understandably worried web searchers click on the link, they would find that acute kidney failure may present with no symptoms at all, but if they have any symptoms, including pain, they should immediately seek medical care.

Changing the search criteria from a person of my age to a child’s and looking for sources of a cough, the list once again goes from “reasonable” to “completely insane.” At the top are perfectly sensible answers like the common cold or asthma, but I laughed in bemused astonishment to come across “radiation sickness” and “ricin poisoning” on the list.

What’s even more absurd is that those two supremely unlikely causes of a childhood cough are listed higher than whooping cough, which actually affected nearly 30,000 patients in 2013 (PDF). And “swallowed object” for a young child is certainly something to consider well before you start worrying about undetected nuclear fallout in your area, despite its place way at the bottom.

This is how people end up totally freaking themselves out over common symptoms of mild illnesses or injuries. Thus far, nobody has ever called me because they’d read online that their child might have ricin poisoning, but it’s completely bananas that there’s even a plausible basis for such a turn of events.

There are many sources of reliable medical information on the Internet. I’m personally partial to the Mayo Clinic’s online resources, for example. Though I’m no great fan of Dr. Oz, his list of good websites isn’t half bad, either. But even the best resource can feed into unfounded anxiety if you end up there researching a bogus condition suggested elsewhere.

It’s probably a fool’s errand to try convincing people to stop Googling their symptoms outright. Most of the parents who tell me they’ve done it admit somewhat abashedly that they knew it was probably a bad idea to begin with, but curiosity is hard to contain and uncertainty hard to tolerate in the hours before my office opens. Some page me in the middle of the night, but end up hitting the computer anyway. Mostly they’re just relieved when I tell them their child’s freckle isn’t an incipient melanoma.

But what I’d really prefer is that they’d forgo the Internet search and ensuing anxiety entirely, and just wait until a proper examination can be done and a reasonable diagnosis made. I hope most of my patients trust me more than the Internet, and in the end it’ll save them needless worry. I can tell bug bites from hives, and suspicious moles from benign ones. And I will never tell them I think the problem could be radiation sickness.