Is there such a thing as a transformational comedian? Comics such as Chris Rock, Louis CK or Tig Notaro now seem to occupy positions of cultural clout held formerly by The Great Writers. The most prominent comics, truest lightning rods, appear as first citizens, giving voice to the most pressing issues of our times. It was probably during the ’60s that claims to Transformative Meaning first slipped free from The Great Writers. On The Tonight Show, must have been, in a scrum between Norman Mailer, Gore Vidal, William F. Buckley, and Susan Sontag; you can probably view it online.

Today, while comedians wax philosophical on subjects far-and-wide, novelists read to near-and-dear audiences, moving from laugh line to laugh line. If you miss one, no worries—here comes another. Is this cause for complaint? Transformative Meaning sinks under Big Information, everyone neck-deep—or deeper—in a flood of statistics. Creativity can be crowdsourced, the prevailing theory goes, and personal taste is nothing more than dots on a grid. Categorically speaking, the individual begins to seem frankly a little absurd, retrograde like the wheel on a first generation iPod. Our screens will always know what’s next before we do. Or that’s the basis of their claim to our attention. Voracity supersedes care, and then, wow—

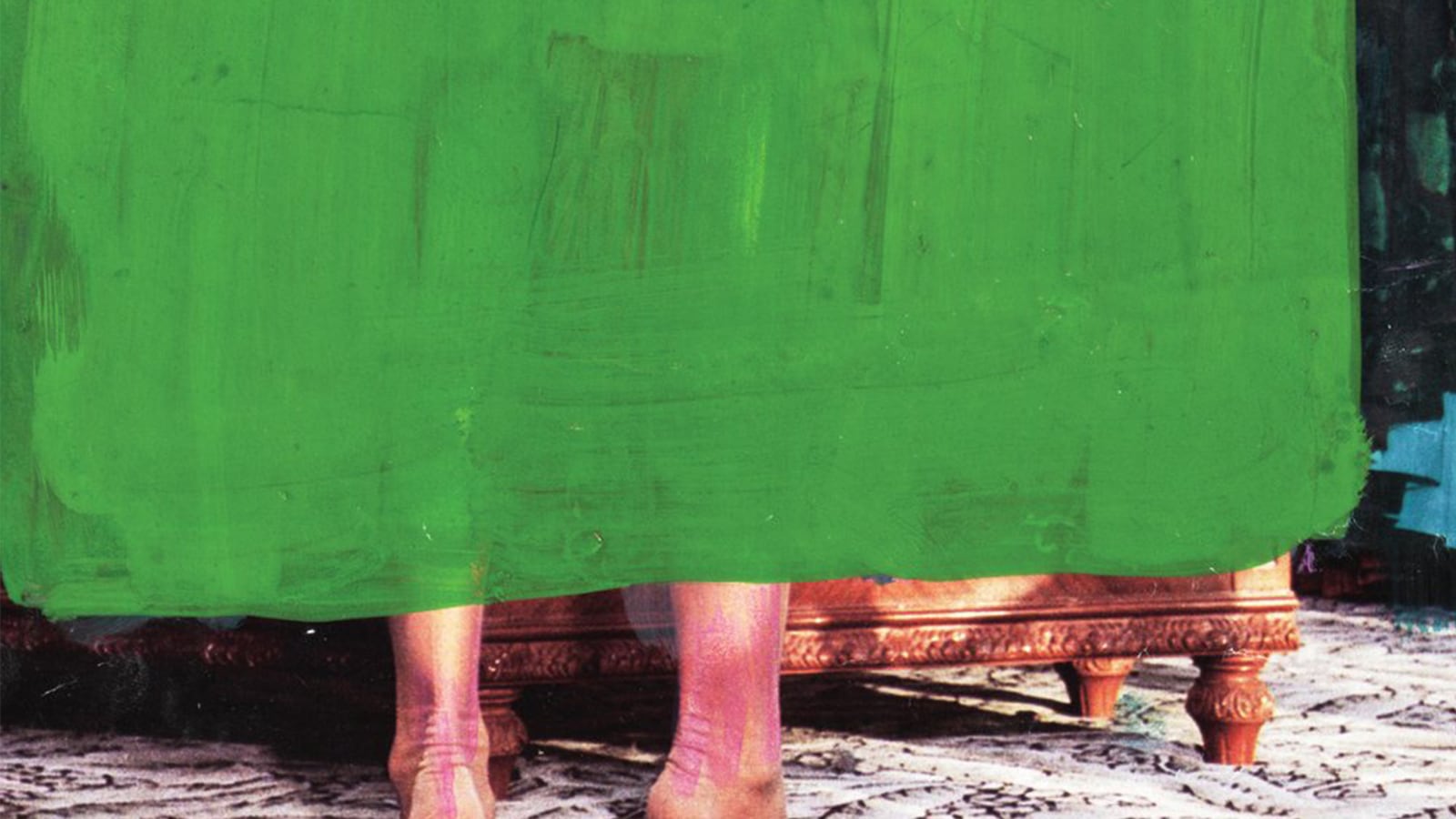

Along comes Nell Zink’s The Wallcreeper. An American expat living in Bad Belzig, Germany, first-time novelist Zink arrives with a deftly delivered debut and a politically prickly crack-up. Like Joseph Heller, Renata Adler, Lorrie Moore, and Donald Antrim rolled into a super-fun ball and zanily caromed off the walls of the cell from which you, me, and Miranda July are watching the desecration of the planet (thinking the whole while, “I’m pretty sure there’s a better way”), Zink’s novel zips across the narrative horizon.

Her protagonist, Tiffany, happens to think a lot. She’s a sort of crackerjack intellectual, and much of The Wallcreeper’s comedy and tension arises in how the unapologetic intellect can still get so much wrong. The entire novel, you wouldn’t know at first, occurs in retrospect, but retrospection so wind-shorn and lean that Tiffany’s youth seems to have concluded only a minute before the opening page. “I’ve never met anybody I can be entirely sure I’ve actually met,” she confides in a first-person narration that feels like a long confession.

Yet winning, all the same. And winning because funny. And funny because delivered with signature swerve and gasp-worthy turns whose comic beats—little pauses before a twist—fall into place like Mad Hatter clockwork.

Tiffany has married young to a guy named Stephen. From Berne, Switzerland, their present address, she recalls meeting his parents in the U.S.A. Pause as you read for each conjunction, every punctuation mark, Zink’s tonal inflection points. Imagine a speaker pacing onstage: “His father sat me down on the dock behind their house and advised me to enter into a suicide pact effective on Stephen’s fiftieth birthday. I said, ‘If I make it that long,’ which was the right answer.”

Ha-ha-ha.

Tiffany and Stephen are very different people. Their only shared passion is bird-watching, a passion for which Stephen is keen and Tiffany getting better all the time: “‘Birds are quantum,’ he would say blandly. ‘If you can even figure out where they’re hiding, it’s too late to see them as they truly are. There’s no such thing as birdwatching. It’s an illusion for stupid people.’”

Says the avid birdwatcher. Ha-ha-ha.

Of Berne, Tiffany observes, “Continuity of an aesthetic that had become an aesthetic of continuity. That was Berne.” And: “Berne was where I could become most completely myself—possessive, shrewish, lonely. There was nothing to retard my self-actualization.”

Ha-ha-ha.

Out of boredom—although really for a host of reasons—Tiffany takes a lover with whom the sex is wonderful, the intellectual connection less so:

“We had loving, beautiful sex just as soon as we could get ourselves to stop talking—loving and beautiful in the expressionist, pathetic-fallacy sense in which you might say a meadow was loving and beautiful even if it was full of hamsters ready to kill each other on sight, but only when they’re awake. I mean, you just ignore the hamsters and look at the big picture.”

Can you hear Zink’s audience losing composure, giggling, snorting, slapping their tabletops? She is essentially doing an impression: Tiffany as Werner Herzog—playing knowingly on German-native Herzog’s obsession with the erotic and murderous. Reader, rest assured, Zink delivers dark laughter, enough to satisfy your inner Werner. Consider The Wallcreeper’s epigraph, courtesy of decided straight man Ted Hughes: “I kill where I please because it is all mine.” The entire narrative that follows plays as an extended comedic rejoinder to masculine hubris.

Yes, you’ll find a preoccupation with the kind of crisis of identity that blossoms in the absence of authority. All that, along with the titular wallcreeper, Stephen and Tiffany’s curious pet. Maybe you’ll wonder how funny it really is, the life that Tiffany’s describing, or how probable the odds of planetary environmental equilibrium given the full calendar of human venality, all our ways of going wrong. Says Stephen, “‘If it weren’t for global warming, we’d be under an ice sheet a mile thick right now.’ He gestured toward the mountains. ‘But look at us. Earth as far as the eye can see. I love global warming! And I love you!’”

Maybe you’ll wonder.

And away The Wallcreeper goes.