MONG LA, Burma — The first noticeable thing in this Burmese town that borders China’s Yunnan Province, is that they really like the Chinese character xin. Half of the businesses seem to have that character in their names: Long Xin (long means dragon), Fu Xin (fu means blessing), Xin Hao (hao means grand), Xin Xin. Xin is three copies of jin, which means gold, stacked in a pyramidal configuration. That’s what this place is for many Chinese settlers: a western frontier where fortunes are made.

Mong La is a strange case. Twenty years ago, it was a collection of small huts. But now, its downtown is a cluster of cellphone stores, clothing stores, cheap hair salons, and hardware stores surrounding a center of food stalls that serve seemingly all the various cuisines of China. Every business is owned by someone from China, and most employ Chinese migrant workers rather than local Shan State Burmese. The television channels are from China, not Burma. The only Burmese brand that can be found in grocery stores is Myanmar Beer. The United Nations built the water supply network in 1994, but the town’s electricity comes from China, and the main telecommunications provider is China Mobile. Dial a number for someone who lives or works in Mong La, and you’ll have to use an area code for Xishuangbanna, Yunnan Province.

The town boasts a Drug Elimination Museum and the Burma-China Friendship Pagoda, as well as elephant and crocodile shows, to justify the creation of tour packages in China, allowing tour operators to bus in Chinese citizens who can’t afford more comfortable visits in nearby Southeast Asian countries. Within the museum, one can find a picture of someone named Sai Leun buddying up with Tatmadaw (Myanmar Armed Forces) generals as they congratulate themselves for a job well done in ridding the region of opium and heroin. What isn’t stated in the caption is that Sai Leun’s real name is actually Lin Mingxian, the drug lord and king of the hill in Mong La.

Lin heads the governing body in Mong La, which is not the central government in Yangon but the former rebel army known as the National Democracy Alliance Army-Eastern Shan State (NDAA-ESS) in what is now an autonomous part of Burma.

Publicly, NDAA-ESS have the general attitude that the wildlife trade is healthier for the region than the opium trade, so Mong La has been previously reported as a hub for the trade of endangered animals. On the surface, that looks like the truth. Along one edge of the downtown market, a few women still sell tiger pelts, mummified tiger paws, pangolin scales, dried elephant skin, porcupine quills, deer antlers, and tiger penises… or so it seems. I consulted several practitioners of traditional Chinese medicine, and one of them took a walk in the market with me. They all said that most of those animal parts are fake. “The tiger paws are actually from large dogs, with claws attached to them. The pelts are dyed dog furs. The ivory is just bone from a farm animal, most likely an ox. The rest is probably plastic,” he told me. “The only thing that is real here is probably the set of deer antlers, maybe some of the pangolin scales. Those aren’t too difficult to come by.”

That the body parts were fake actually made sense. Many of these items are protected under the CITES agreement, and selling them in the open invites too much unwanted attention, even for a backwater vice town. If those items were in such high demand, and the prices could go so high, they wouldn’t be spread on the ground of a wet market between heaps of bananas and heads of cabbage. When I asked one of the women whether the animal parts were genuine, one of them laughed and said, “These things are only real if the person buying them thinks they are real.”

Chinese tourists see Burma as an exotic place, where women wear gold loops around their necks and endangered animals are still hunted by mountain tribes. (Some tours play up these stereotypes, and arrange for visits to a park named Ancient Valley, where employees are dressed in the garb of ethnic minorities and gawked at by camera-toting tourists.)

The Chinese may once have come here for the wild animals (when the parts were still real), but that’s no longer the case. A cluster of casinos are a half-hour’s drive away from downtown, with names like Galaxyse and Hilton. New betting houses and hotels are being erected. The casinos have signs by their main entrances that say no Chinese citizens can enter, but the staff are all Chinese, the language spoken is Putonghua or dialects from Yunnan, and every fist is holding a brick of renminbi. In fact, according to Father Mario Mardu, a Catholic priest based in Mong La, the only people who aren’t allowed to enter the casinos are actually NDAA-ESS officers. Many of the younger officers are Father Mardu’s former students.

Father Mardu also said that there used to be over 1,000 tourists entering Mong La from China every day. That was when the casinos were in the center of town. But the Chinese shut down those casinos in 2005. The owners—all Chinese citizens—were banned from returning to their home country. It took a few years for them to set up their operation again, this time as a pseudo-oasis connected to downtown by a dirt road.

In one of the casinos, I was mistaken for an undercover Chinese police officer. A pit boss arranged for a van to take me back to my hotel room, and said he’d send “a young girl” to look after me, “like [they] do for all the important guests, like police officers.” (I declined.)

The casinos might attract a specific kind of visitor, but they offer ample job opportunities for Burmese workers. The presence of Chinese traders is also key to the region’s survival and prosperity. In February, fighting broke out between the Myanmar Armed Forces and the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA) in Burma’s Special Region 1, north of Special Region 4 where Mong La is located. Because of the battles, the Burmese government halted all transportation of goods from within Burma to the autonomous regions, cutting all domestic supplies to the Shan State residents. However, commerce on the ground depends on China more than the rest of Burma, so there has been little impact on life in Mong La.

NDAA-ESS wants self-governance, not independence. The people in Special Region 4 consider themselves to be part of the Burmese nation, but they want to maintain their own armed forces for defense, an idea rooted in ethnic identity. This is in conflict with the Burmese constitution, which concentrates power in the hands of the Tatmadaw.

Back in Yunnan, it’s easy to spot anti-drug murals that depict Chinese police officers capturing drug mules. Chinese media plays up their successes in maintaining border security, yet many who visit Mong La do so by hiring motorbikes to cross into Burma via mountain paths. They do this partly for the thrill, and partly to save a little bit of time and money from having to acquire an exit permit and pay the associated fees. Heroin is easily smuggled into China via the same routes, and there have also been cases of human trafficking.

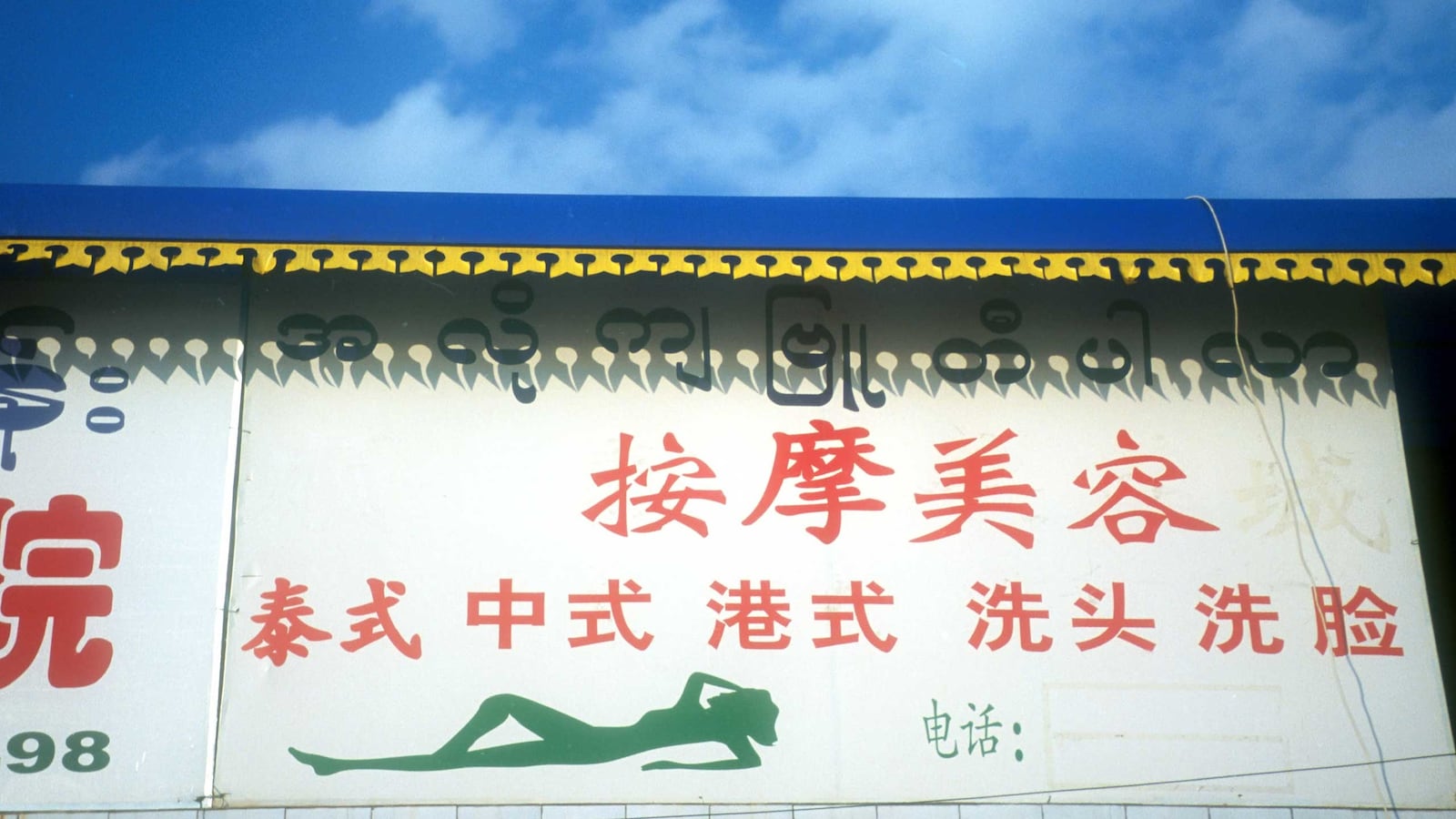

As night falls, the “bars” in downtown come alive. They occupy a single alley. Within the premises are small compartments, haphazardly cobbled together, just big enough to fit two people per cubby. The bars don’t serve drinks, and young women congregate by the front doors. Prostitution, like gambling, is legal in Mong La. The place might look like any fourth-tier Chinese industrial town, but the debauchery doesn’t bother with fig leaves. They don’t bother to hide behind massage parlors without a single drop of massage oil or hair salons without a single pair of scissors. A few drunk men stumble in, waving red bills with Mao Zedong’s face on them—perhaps their winnings for the day—and disappear into the cheap space between inebriation and vice.