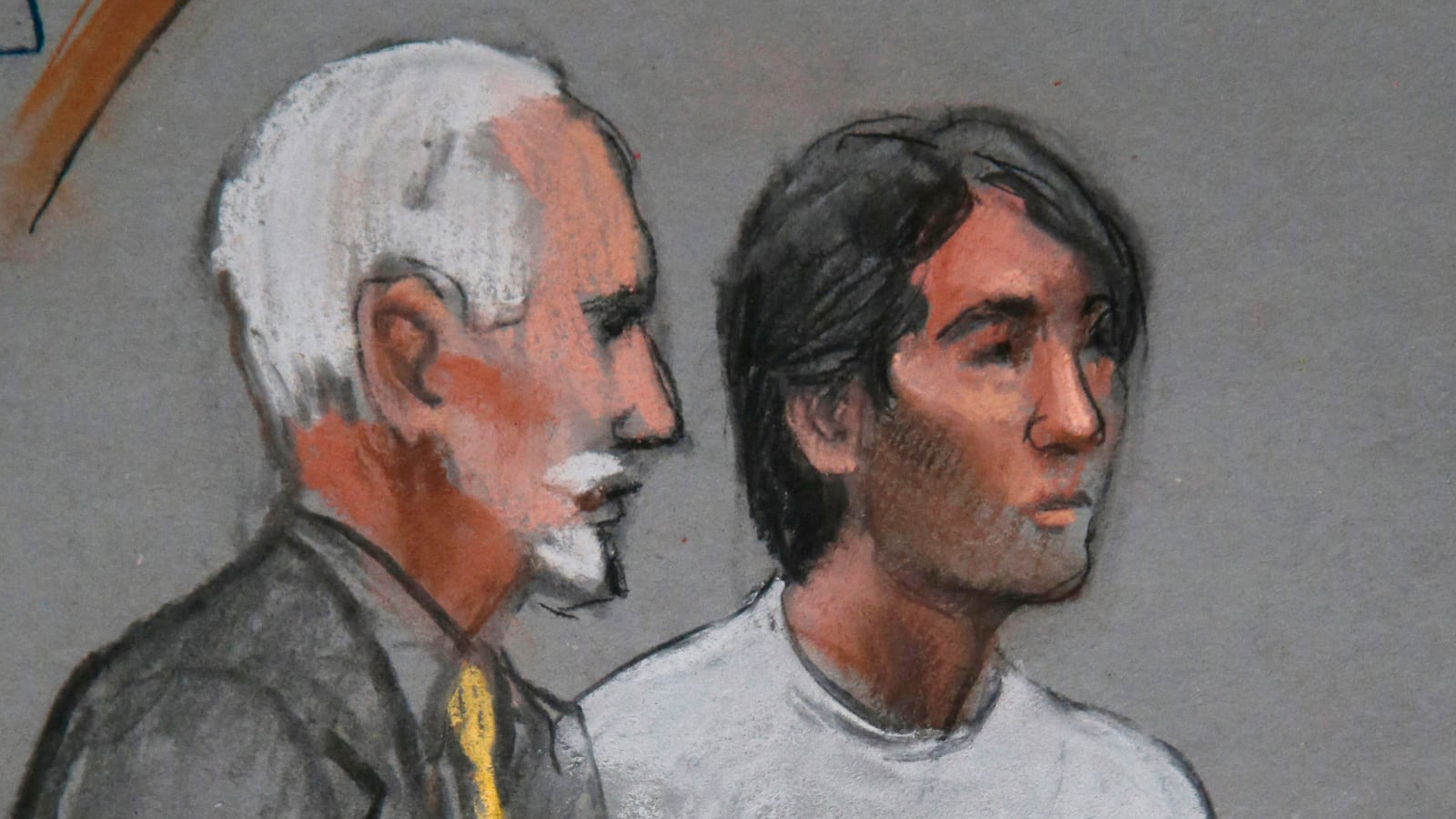

Khairullozhon Matanov deliberated with his lawyers three times before hesitantly pleading guilty yesterday to all four counts of obstructing the 2013 investigation into the Boston Marathon bombing.

This was not an easy decision for him to make.

“The whole case is mystery,” he wrote to The Daily Beast last fall. “FBI is trying to destroy my life.”

If Judge William Young agrees to the deal, Manatov will get 30 months in prison, including the 10 months he’s already served. If he goes to trial and is found guilty, he could spend the next 20 years behind bars.

Even in pleading guilty, Matanov asserted his innocence.

“You’re afraid if you go to trial you could be found guilty of all four of these charges and the sentence might be longer than the 30 months?” Judge Young asked. “Is that it? That you think you are not a guilty person but given the circumstances you’d rather [not] go to trial?”

Matanov’s dark bowl cut bobbed slightly.

“I signed a deal and I found guilt most fitting for my situation.”

Matanov, a 24-year-old cab driver from Kyrgyzstan, had been living in Quincy, Massachusetts, before he was apprehended by federal agents in the dark early-morning hours last May. Since then, he’s been behind bars, oftentimes held in a cell by himself.

By all accounts, Matanov’s life in America had been going well up until the marathon bombings. He came to the U.S. in 2010 on a student visa and later received asylum. After attending Quincy College for two years, he dropped out to take a job as a taxi driver. He was well-liked at the the cab company. He made a few friends at his mosque with whom he’d play pickup games of soccer.

Then one of his new friends, Tamerlan Tsarnaev, allegedly planted a pressure-cooker bomb at the Boston Marathon finish line with his younger brother, Dzhokhar, and everything in Matanov’s life changed forever.

As Matanov pleaded guilty to charges that he obstructed the investigation into the attack, Dzhokhar was being tried for his life in a courtroom below.

The Tsarnaevs’ terror spree surprised Matanov as much as anyone, and the indictment against him makes that clear. “The government has no evidence that Matanov had foreknowledge or participated in the bombings,” it states.

But if the government has no evidence Matanov participated in the attack, it’s not because the FBI didn’t look hard enough.

For months after the bombing, FBI agents trailed him constantly. In Matanov’s bail hearing, an agent testified that Matanov once got out of the car to talk to an agent he knew was following him.

At one point agents called his lawyer, Paul Glickman, to tell Matanov to stop speeding. He complied.

Federal agents monitored Matanov even as he slept. At night, an aircraft would circle his West Quincy home. The unexplained night flights became a point of local mystery and outcry. At the time, spokespeople for the Federal Aviation Administration refused to say who was piloting the plane and why.

And then, more than a year after the attack—and more than a year after the crimes for which Matanov is charged are alleged to have taken place—he was arrested.

When he wrote to The Daily Beast last November, Matanov said he was innocent, and perplexed at the position he found himself in.

“I don’t understand what on earth I have done to be treated this awful way and prisoned [sic] for such a long time? Now on top of that media made me already guilty even before my trial happen,” he wrote.

The media and the government may have made him look guilty, but not for the crimes he’s charged with committing.

The indictment, written by U.S. Attorney Carmen Ortiz, notes that Matanov and Tamerlan once went “hiking up a New Hampshire mountain in order to train like, and praise, the ‘mujahideen.’”

Matanov allegedly called Tamerlan less than an hour after the bombing. He then allegedly met the Tsarnaevs at a Somerville kebab joint for dinner. Later, he allegedly told his roommate he thought the bombing “could have a just reason, such as being done in the name of Islam, that he would support the bombings if the reason were just or the attack had been done by the Taliban.”

He then allegedly added his own slightly confused interpretation—“that the victims had gone to paradise.” The government also maintains that Matanov possessed videos with “violent content or calls to violence.”

It’s possible that Matanov has some beliefs that many or most find abhorrent. Nothing about that is criminal.

“There is no obligation to turn in your neighbor,” explains Nancy Gertner, a former federal judge and Harvard law professor. “It is a crime not to tell on your neighbors in Soviet countries, but not here.”

On the Friday after the bombing, when Dzhokhar was hiding in a boat in a Watertown backyard, Matanov voluntarily went to the Braintree Police Department to tell law enforcement about his connection to the brothers.

He then agreed to be interviewed by the FBI several times after that.

His charges—and eventual conviction, if Young agrees to the plea deal—all stem from the actions Matanov took next. The government is charging him of one count of destroying documents in a federal terror investigation and three counts of making false statements to the FBI.

The false-statement charges stem from those voluntary interviews with the FBI in which he admitted he ate with the Tsarnaevs, but allegedly lied about inviting them to dinner, lied about the number of times he checked for their photos online before going to police, and lied about ever watching the “violent” videos that had been downloaded to his computer.

The documents he’s accused of destroying are those violent videos.

He’s also charged with clearing his search history on Google Chrome.

Ortiz was able to charge Matanov for clearing his browser history, and deleting his own personal computer files, under the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (Sarbox)—a law Congress enacted in response to the Enron scandal to target business malfeasance. Within Sarbox is a rule to prevent businesses from destroying records that could serve as evidence of their own criminal activity.

Sarbox is a contentious issue in trials of the Tsarnaevs’ other associates, too. Two of Dzhokhar’s college friends were charged under Sarbox for throwing Dzhokhar’s backpack into a dumpster after recognizing their friend’s face on the FBI’s Most Wanted list. Dias Kadyrbayev pleaded guilty. If his plea is accepted, he’ll get less than seven years in prison. Azamat Tazhayakov was found guilty and faces 25 years in prison, but is asking for a retrial based on a recent U.S. Supreme Court ruling on Sarbox.

In Yates v. the U.S., a Florida fisherman took his case to the Supreme Court after he was charged under Sarbox for throwing out undersized fish. Last month, the court ruled in his favor—that Sarbox is only applicable in cases where “objects one can use to record or preserve information” are destroyed.

Not fish, ruled the court. And not backpacks, Tazhayakov’s lawyer argued in a recent motion. (He claims Tazhayakov was unaware that the backpack contained a thumb drive.)

The Yates ruling isn’t applicable to Matanov, because the search browser history he cleared and the files he destroyed are still technically a record. But Gertner says Ortiz’s office is taking Sarbox too far in this case, too.

That’s because Matanov is charged with obstructing an investigation into a non-crime: his own views.

“The notion that you have an obligation to keep your information lest the government look at it is totalitarianism,” she argues.

Think of it another way, outside of the context of terrorism. Imagine your friend, with whom you enjoyed listening to rap music like Notorious B.I.G’s “Ten Crack Commandments,” was arrested in a big crack sting. You don’t sell crack. You didn’t even know your friend sold crack. Maybe he mentioned it, but you thought he was playing around.

But you do know federal investigators will now want to talk to you. And, in fact, you want to help. Songs about crack are one thing, but crack itself is a different story, you figure.

To keep up appearances, you take down your Biggie poster, delete some of your music, and clear your browser history. The Matanov conviction could set up a precedent whereby you could serve federal time for any of those actions.

So what’s a little erosion of liberty in the name of national security? The government doesn’t want to prosecute rap enthusiasts. They’re after the terrorists. Bad guys who kill children and blow up cities. And, after all, Matanov lied.

But whether Matanov knew his statements were a “materially false statement of fact” in the bombing investigation isn’t totally clear. And that’s what Young says the government would have to prove.

One of his lying counts—about whether or not he watched the videos on his computer—is in reference to an investigation into himself, for which the only thing the investigators found to charge him with is his obstruction into that investigation.

He also lied about how soon he went to law enforcement after recognizing Tsarnaev’s photo. But, by law, he wasn’t obligated to go to the authorities at all.

And the government argued that Matanov lied when he said he didn’t plan to have dinner with the Tsarnaevs the night of the bombing. Instead, he said he just ran into them at a Somerville kebab joint. This, the government argues, interfered with the agency’s efforts to pinpoint the Tsarnaevs’ every movement that day. Of all the charges, this one appears to have the most weight.

The way Gertner sees it, Matanov made “a calculation that he cannot have a fair trial here, that any connection to the Tsarnaevs will be unfairly heard.”

But Don Borelli, a former assistant special agent in charge in the New York Joint Terrorism Task Force who is now with the security company the Soufan Group, says that lying to federal agents—no matter how trivial—is dangerous.

“You can’t be collecting a bunch of lies or self-serving information,” he explains. “You waste time, you waste resources, and, in theory, sometimes it can cost lives.”

Pressing charges against people who come forward may cost lives, too.

Michael German, a former FBI agent and terrorism specialist now with the Brennan Center for Justice, says the repercussions of overzealous prosecution can be damning to national-security efforts.

“It creates a chill for any cooperation,” he says.

Cases like the one against Matanov are antithetical to the Department of Homeland Security’s See Something, Say Something effort, he explains.

“It creates a potential for blowback—an atmosphere where no one talks to the FBI at any time about anybody because any crime someone does report opens themselves up to liability.”

Attorney Bernie Grossberg, who represents one of the Tsarnaevs’ friends, says German’s idea is backed up in theory and in practice.

Grossberg’s client requested that his name not be used in this story for fear his connections to the Tsarnaevs might harm his career.

“What’s happened is everybody who has spoken [in] the Chechen community in Boston has wound up having legal problems or potential legal problems,” he explains. “They all knew each other and now they are all deathly afraid of doing anything. And these are all law-abiding citizens.”

Grossberg’s client has been called to a grand jury, and subpoenaed by the U.S. Attorney’s Office. He has exercised his Fifth Amendment rights against self-incrimination both times and plans to do so again after being subpoenaed by Dzhokhar’s defense team last week.

“He’s damned if he does and damned if he doesn’t,” explains Grossberg. “He basically takes the position, ‘I don’t know anything, and if I did I’d have my own legal problems.’”

Sarah Wunch, a staff attorney at the Massachusetts chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union, says it isn’t just Grossberg’s client.

“There was a period of months where we were getting a bunch of calls from people who knew the Tsarnaev brothers and [were] getting many visits by the FBI and threatened with grand jury subpoenas,” she said. “It began to feel like they were harassing people who tried to come forward.

“The government was shortsighted in the way they were treating these people. If you want to make people come forward when they see something and say something, you don’t want them to be scared of being ensnared.”

So why is Ortiz’s office pressing charges against Matanov at all?

Some believe it may just be Ortiz’s style to seek the most severe punishment possible at all times. It was Ortiz’s office that filed charges against Internet activist Aaron Swartz that could have sent him to prison for 32 years for the alleged dissemination of the contents of an academic document database, JSTOR. The documents could have otherwise been seen freely with a library card. The looming sentencing is widely credited to have caused the 26-year-old to take his own life.

Matanov says he was being pressured to provide information he didn’t have.

“U.S. Attorney’s Office thru my lawyer offered, to tell them about ‘terrorists,’ which I say I have no connections to any group, and I don’t support any kind of violence at all,” Matanov wrote to The Daily Beast last fall.

German says the government often seeks long sentences from people they suspect of terrorism.

“The reason the sentence in this matter is so severe is in order to compel cooperation,” he explained. “Certainly in other terrorism cases, there is a government assumption that the person may know far more than they actually know, which puts the person in the bind.”

Neither his lawyer nor Ortiz’s office would say if Matanov’s plea agreement entailed any kind of cooperation.

Another possibility is that the government is prosecuting Matanov for obstruction charges out of an abundance of precaution, rather than because they believe he hindered the investigation or because of the statements he made to his roommate and the “violent” videos.

“There may be other things that rise to the surface that don’t rise to charges,” explains Borelli.

German, on the other hand, says there is a problem with what he called the “Al Capone theory”—charging people for one crime because you believe they committed another. Capone was the notorious Prohibition-era gangster who was charged and convicted for tax evasion.

German thinks the bureau uses that method of prosecution against people who haven’t committed a crime but may be interested in extremist criminal ideology. German says the FBI has a theory “that the radical ideas led to the violence,” but he says that’s not always the case.

Not only that, but targeting people who have one “viewpoint as opposed to another,” as the former FBI agent puts it, might have even more serious repercussions in any future efforts to persuade those with information to come forward. The people who may have a superficial interest in radical beliefs—or have relationships with those who do—may have the most information, but they also have the most to fear.

“When you have a national event like that you have a lot of people calling with crazy information,” said German. “If the only people prosecuted are people the government disfavors, that would be a big issue.”