Michael Lewis wasn’t the first writer to gain extensive access to the general manager of a Major League Baseball team, but he’s proved to be the most influential. Moneyball, his book about Oakland A’s exec Billy Beane, was published 12 years ago, and ever since, reporters looking to replicate its success have been cozying up to posterity-minded professional sports GMs, chronicling their purported genius in a series of fitfully insightful and often fawning books. The most recent title in this field is by a longtime baseball writer named Steve Kettmann, and it’s a conspicuous example of the genre’s many perils. Simultaneously convinced of his subject’s eminence and desperate to be ahead of the curve, Kettmann has manufactured a storyline that simply doesn’t exist, at least not yet.

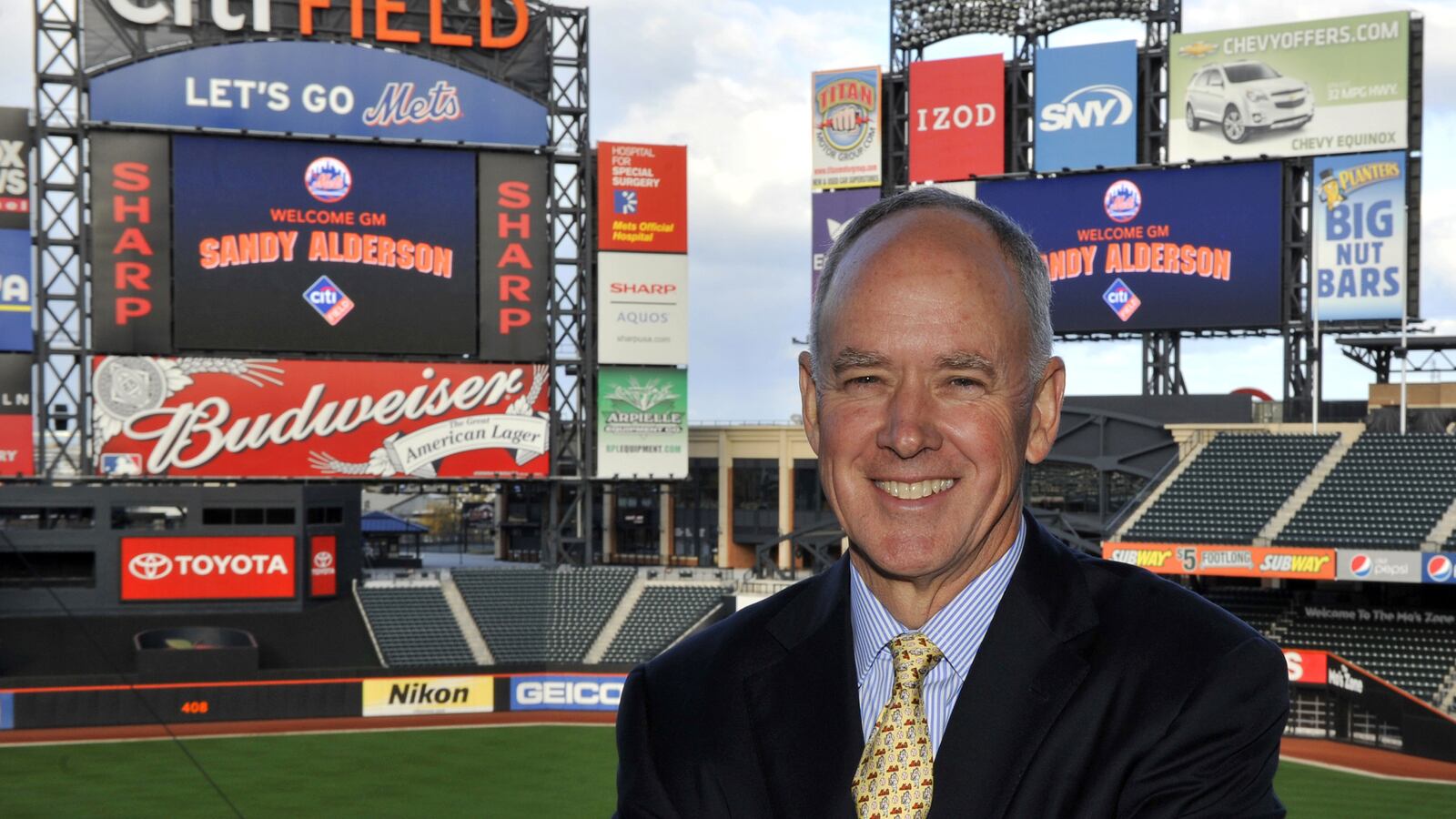

As a Mets fan of long standing it pains me to do so, but I must point out that substantial portions of Kettmann’s Baseball Maverick: How Sandy Alderson Revolutionized Baseball and Revived the Mets are utter BS. “Revived”? There’s no denying that Alderson inherited an organization headed in the wrong direction when he was hired as the Mets’ GM before the 2011 season. But under his leadership, the team has put together four consecutive losing seasons; their best showing during the period was last year’s 79-83 record.

So until he puts together a winning season, maybe let’s hold off on celebrating him as a savior?

Kettmann says he spent about four years on this book. During this time, he developed a rather serious case of tunnel vision, vastly overinflating Alderson’s importance. “If the Mets are going to be a playoff team not in some distant, dreamy future, but in 2015,” he writes, “they need Alderson to be the public face of the team the way he was for the A’s back in his Oakland years.” This is nonsense, on a couple of levels. For a start, there’s not a baseball fan in this country who, when talking about those excellent A’s teams of the late ’80s, starts the conversation by praising the front-office work of then-GM Sandy Alderson—we think first of Dennis Eckersley, Dave Stewart, Mark McGwire, and Jose Canseco, not the guy who watched them from an executive suite. Second, why on earth would the Mets won-loss record have anything to do with how many interviews Alderson gives, or if, as Kettmann suggests, he goes on The Daily Show to talk baseball with Mets fan Jon Stewart?

Kettmann’s contention—that Alderson has rejuvenated the Mets—is based on the idea that he’s assembled a promising roster on the cheap. The team’s payroll was more than $140 million as recently as 2009. But owner Fred Wilpon’s financial health took a tumble when his longtime adviser Bernard Madoff was revealed to be a massive scam artist, and the amount the team spends on players has been slashed. Though the Mets enjoy a host of big-market advantages, the team’s payroll will be around $90 million this year, putting it behind about two-thirds of Major League Baseball’s 30 clubs.

Faced with diminished resources, has Alderson spent smartly? We don’t know yet. More than a quarter of this year’s payroll will go to Curtis Granderson and Michael Cuddyer, a pair of aging outfielders Alderson signed as free agents. Cuddyer has only just joined the team, but he’s 36 and injury-prone. Granderson, meanwhile, is 34, and had an underwhelming first year with the Mets in 2014; he’s owed about $45 million for the three seasons ending in 2017.

Wisely, the team is building its future on pitching. Alderson can’t take credit for the Mets top two starters, however; Matt Harvey and Jacob deGrom were both drafted before he joined the organization. Alderson’s most promising young acquisition, the hard-throwing right-hander Zack Wheeler, recently blew out his elbow and will miss the 2015 season. Though the team has developed plenty of prospects on Alderson’s watch—the Mets had the 25th most talented farm system in 2010, according to Baseball America, but had climbed to No. 8 by last year—the big-league club still relies heavily on players who predate Alderson: Five of the eight position players expected to be part of this year’s opening-day lineup were already part of the Mets system when he took the job.

In other words, crediting Alderson with rebuilding the Mets is silly, because it’s not yet clear that anybody’s rebuilt anything.

Kettmann, the ghostwriter of former slugger Jose Canseco’s steroid tell-all Juiced, does better when he acts like a biographer. His subject has led a genuinely interesting life. An Air Force pilot’s son, Alderson lived in Japan and England as a kid, and before college, he did a few months of low-level data collection for the CIA (“It is not a job he has ever disclosed publicly, prior to the publication of this book,” Kettmann writes, more impressed with his mini-scoop than his readers are likely to be.) In 1968, while a student at Dartmouth, Alderson made his way to Vietnam and wrote an article about the war for his student newspaper. He returned as a Marine platoon commander two years later. In 1973, when Lyndon B. Johnson was buried, Alderson was one of the officers picked to guard the late president’s casket. A photo of Alderson taken that day, Kettmann says, was later used in one of those “The Marines are looking for a few good men” recruiting campaigns.

In the early ’80s Alderson, by then a Harvard Law School grad, began working for the Oakland A’s as a lawyer. During his decade-and-a-half run as the team’s GM, the A’s were perennial contenders and played in three consecutive World Series, winning in 1989.

It’s an exaggeration to claim, as Kettmann does, that Alderson “revolutionized” baseball, but he did make some innovations during his various stops (after he left Oakland, Alderson was a high-ranking MLB executive in the mid-’90s, and ran the San Diego Padres for a few years in the 2000s). Alderson was one of the first general managers to understand the importance of data, and in the ’80s, long before many of his peers, he employed number-crunchers who helped him determine which free agents were worth signing. He encouraged players to lift weights when other GMs were discouraging strength training, and he “hired the first mental performance coach in baseball,” Kettmann writes. While working for Major League Baseball, he reformed the way that umpires are evaluated. Kettmann also credits Alderson with modernizing MLB’s relationship with players and agents from the Dominican Republic, citing other reporters who assert that “(o)n his watch … progress had been made in pursuing identity fraud (and) cracking down on the use of performance-enhancing drugs.”

This last one’s a bit rich, given that Alderson—like many others in and around the sport—seems to have looked the other way when some of his muscular home-run hitters were using performance-enhancing drugs as members of the Oakland A’s in the ’80s and ’90s. During the 1988 American league playoffs, Kettmann notes, “fans at Boston’s Fenway Park taunted (Oakland’s) Jose Canseco with cries of ‘Ster-oids!’” “Alderson,” he writes, “was starting to wonder by then if it might be a case with Canseco of where there was smoke there was fire. But he had no notion of how to assess the validity of such speculation. He was a man who loved information, accurate, detailed, credible information, and when it came to suggestions of steroid use, all he had was hazy conjecture.” There’s a name for what Kettmann’s done here: It’s called letting your subject off the hook.

Kettmann is also a master of the banal quote. He tells us that Alderson taught a sports marketing class at the University of California Berkeley. How did it go, Sandy? “The undergraduates were tremendously enthusiastic and the MBA students were very accomplished and creative.” And hey, Sandy, what did you make of your time with the Padres? “I was intrigued by the opportunity … And in retrospect I’m very happy I took it.” They say that potential young fans aren’t taking to baseball because they find the game boring. If that’s the case, let’s make sure we don’t expose them to any of Sandy Alderson’s musings.

Alderson and Harvey, the team’s young pitching star, have gently butted heads a couple of times, most notably last year when they disagreed about how quickly the pitcher would recover from Tommy John surgery on his right elbow, and where he should be doing his rehab work. Unsurprisingly, Kettmann has Alderson’s back on this one, describing Harvey as an egotist devoted to “twin loves, baseball dominance and, well, to put it bluntly, himself.” Kettmann has a tough time hiding his feelings about Harvey, and he comes off like a retrograde moralist when he implies that the pitcher’s performance might suffer this year if Harvey continues “hanging out with supermodels at Manhattan clubs in the wee hours of the night.” Harvey is a single 26-year-old man, and as a starting pitcher, he gets four days off between appearances. So maybe it’s a little weird to worry about the guy’s dating life?

But so it goes throughout Baseball Maverick, a piece of ballpark propaganda that never fails to side with its subject. In defending Alderson at every turn, Kettmann’s more like a publicist than a tough-minded chronicler. He surely didn’t intend it this way, but his book reads like the work of a reporter whose most important audience is the person he’s writing about. Kettmann’s an author with several titles to his name, but here he makes a rookie mistake: He very much wants Alderson to like his book, and in the process, he often seems to have forgotten the rest of his readers.