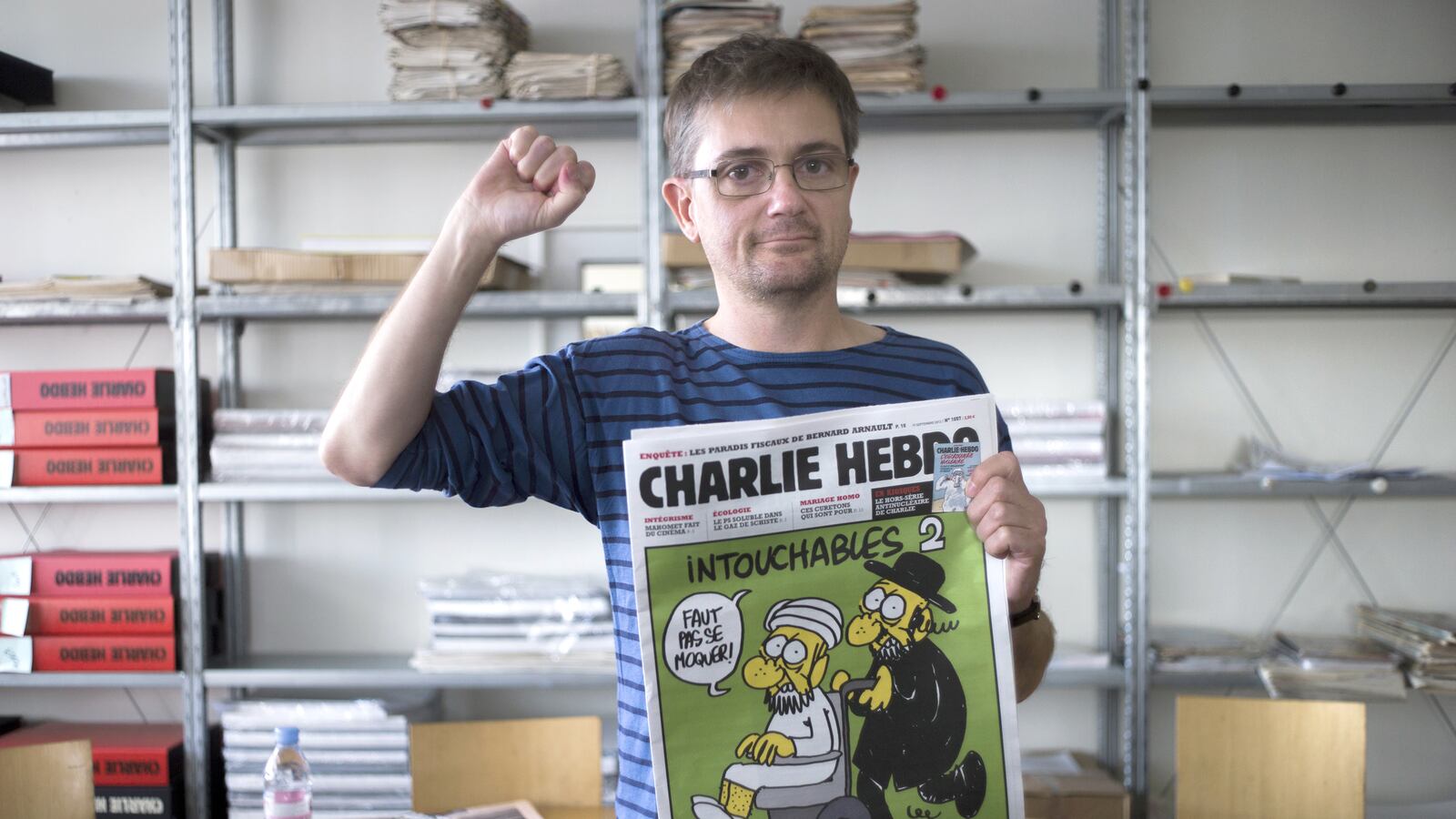

PARIS — The little book published in France today by the editor of Charlie Hebdo who was gunned down by Muslim fanatics in January may be one of the more provocative essays about racism, Islam, anti-Semitism, intolerance—and France—to come out in a long time.

But not because Stéphane “Charb” Charbonnier was an equal opportunity satirist, ready, just for a laugh, to skewer Muslims, Christians and Jews alike. And not because, as some would have us believe, he was defending absolute freedom of the press. That would suggest he did not take sides. That would imply he did not have his own red lines. And that would be a mistake.

This 88-page book with the clumsy title Open Letter to the Fraudsters of Islamophobia Who Play Into Racists’ Hands is the work of an atheist and a communist manqué who thinks religion—all religion—is ridiculous, and all religious extremism is dangerous. But he believes certain principles, like the need to stand against racism and defend the core French republican values of liberty, fraternity and equality are, if not holy, pretty damn close.

Charb writes with contempt, for instance, about the religious groups, both Muslim and Catholic, that took Charlie Hebdo to court in the past. Why would they need to do that if they truly believed punishment would come in the afterlife, he wonders. Why would “God, the creator of the world, the guy with the big shoulders who plays with our planet like a driver stopped at a red light plays with his boogers” need a lawyer to defend him from cartoonists?

By the same token, why would Allah need men with Kalashnikovs to attack journalists, police officers and Jewish shoppers in a Kosher market? Charb did not live to address that question directly, but his fury at religious fanatics and those who make excuses for them gives us a perfect idea what he thought.

Charlie Hebdo had been targeted before, when its offices were firebombed in 2011 as it was publishing a special issue it called Charia Hebdo (Sharia Weekly), and to Charb’s consternation, he found his publication being vilified at the time for incitement, insensitivity and, indeed, racism. (Were he alive today, he might have heard similar criticisms from American cartoonist and humorist Garry Trudeau.)

At the time Charb was writing this new book, just days before he and his colleagues were murdered on a quiet winter morning in their East Paris office, he had spent almost two years in the shadow of an explicit public death threat by Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, which eventually claimed responsibility for the massacre.

In its edition of March 2013, the AQAP online magazine Inspire “publishes a poster with 11 names of personalities accused of ‘crimes against Islam,’ and wanted ‘dead or alive,’” Charb wrote. “I find my name, badly spelled but accompanied by a photo where you can recognized my frightened mug. It was a photo that appeared in the press, takend the day of the [2011] attack on Charlie Hebdo. On this poster, I am in more or less good company: there is the inescapable Salman Rushdie; the Dutch extreme-right leader Geert Wilders; Flemming Rose, the editor of the cultural pages of the Danish Jyllands-Posten, at whose initiative the caricatures of Muhammad were published; Terry Jones, a completely crazy American pastor who burned Qurans, and other happy laureates. ... So that those listed understand well what’s waiting for them, a smoking pistol is shown to the left of the Nazi pastor, on his right, a splash of blood. This clever montage is entitled ‘Yes We Can,’ and under it you can read, ‘A bullet a day keeps the infidel away.’ And finally: Defend the Prophet Muhammad, peace be upon him.’”

But Charb’s publication was on the verge of bankruptcy when he penned this little tome (since the massacre and the massive outpouring of Je-Suis-Charlie emotion that followed, the weekly is now well in the black), and much of the book is an exploration of the attitudes that, at the time, had turned Charlie Hebdo into a minor and often despised fringe player on the French media scene. Its offense, in the eyes of the politically correct establishment, was not just frequent bad taste but “Islamophobia.”

Charb’s central thesis is that the word “Islamophobia” and most of the debate that surrounds it is misleading. He suggests it is an attempt to claim some equivalent of the term anti-Semitism that might be used, not least in the French and European courts, to silence critics and intimidate opponents. But Charb sees no comparison.

“Islamophobia” is mostly a cover for good old racism, he says: a way of sidestepping the real issue. Do an Arab Muslim and a white French convert to Islam face the same kind of discrimination? Certainly not, he says. Does a rich Arab Muslim have the same problems as a poor one? Clearly the answer is no. The “phobia” is really hatred directed at Arabs and Africans and their dark-skinned descendants. It is these people who should be defended, says Charb, not the abstraction of their faith.

“It’s gotten to the point where you could have the impression that the foreigners or citizens with foreign backgrounds in France are only attacked if they’re Muslims,” writes Charb with his usual irony. “The victims of racism who are of Indian, Asian, Roma, black African, Caribbean, etc., backgrounds should think about finding themselves a religion if they want to be defended.”

Imposing the label of Islam on the problem of racism plays right into the hands of extremists, says Charb. Victims of racism are told the problem is their faith, battle lines are drawn, recruits are gathered up for jihad and, in Charb’s view, much of the politically correct and perfectly naïve press is complicit.

He traces in some detail the evolution of the debate about the Danish caricatures of Muhammad, republished by Charlie Hebdo in 2006, noting that his paper had printed its own caricatures of the Prophet many times before that without causing much of a sensation. Not until a small group of religious extremists exploited the issue of the Danish cartoons did it become “a subject capable of triggering hysterical media and Islamic crises. First the media ones, and then the Islamic ones.”

“To put on the head of the prophet of the believers a bomb, that was to suggest that all the faithful were terrorists,” Charb says with evident irony. “Another interpretation was possible, but it was less interesting to the media, since it wasn’t really sensational and, so, less saleable. Muhammad with a bomb in his turban could be a way to denounce the use of religion by terrorists. The cartoon said this is what terrorists make of Islam, here’s how the terrorists who claim the Prophet as their own actually see him.” But that was asking for reason in a world where there is less and less of it.

In his concluding chapters, Charb writes that Catholic extremists are jealous of the success Islamic extremists have had making their faith the issue and dragging in countless of their co-religionaries who, given their druthers, would rather be left alone.

When it comes to what he calls “Jews” and “jews,” making a distinction between the more religious and the rest, he says it is perfectly acceptable to satirize at the same level “the religious extremist Jews who, for example, hunt down the Palestinians on the West Bank with bulldozers and assault rifles and the jihadists who hunt down infidels in Iraq or in Syria.” But he argues that the Holocaust made it clear that anti-Semitism was very real, very racist, and made no distinctions between the religious and the non-religious. “No,” he wrote, “Islamophobia is not the new anti-Semitism. There is no new anti-Semitism, there is the old, hideous and immortal racism.”

In the end, unfortunately, Charb writes a paean to atheism that misses the mark and undermines his earlier arguments. Earlier he noted that “there are not a billion communists left in the world (alas), the Communist Party is not the second party of France (alas), there are (alas) more mosques than Communist Party federations.” Then as he’s concluding his book he writes “it seems that there is no atheist terrorism in the 21st century.”

That may be true. But the scale of atheist terrorism in the 20th, from Stalin to Pol Pot cannot be brushed aside as lightly as that.

The fact is, fanaticism is not limited to those who believe in their nose-picking deities, whether they call them God, Allah or YHVH. Ideologies, too, have their true believers, and they, too, should be skewered by cartoonists like Charb, may he rest in peace.

Photos: Most-Shocking Charlie Hebdo Covers