During the regular season, NBA teams occasionally play each other twice in a row but there is nothing over the course of that time that prepares them for the playoffs. A back-to-back is nothing like a 7-game playoff series. By the second or third playoff game, players on both sides start to get agitated—chippy, as the announcers like to say. The match-ups, the strategies, the pressure and the drama make the NBA playoffs terrific entertainment.

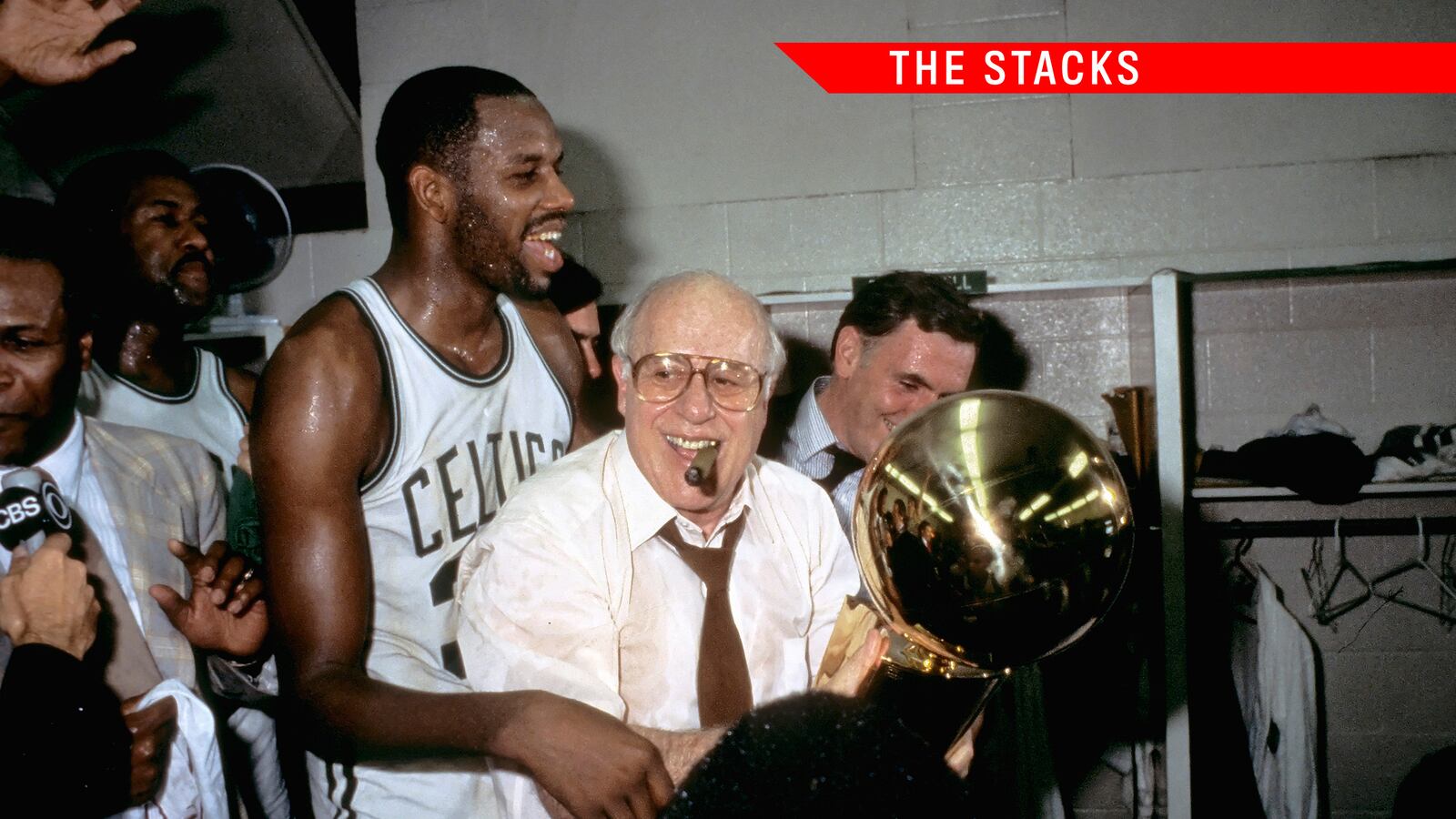

This year we've got stars (James, Curry, Harden), major injuries (Love, Gasol, Conley), and plenty of excitement to go around. What we don't have are the two signature franchises in NBA history: the Boston Celtics or the Los Angeles Lakers. But that doesn't mean we can't take a moment to appreciate the most celebrated coach in league history—Red Auerbach.

Back in 1990, Johnette Howard wrote the following profile on the Boston legend for short-lived but fantastic publication, The National Sports Daily. Howard's career was just taking off. She was part of a talented bunch—that included Peter Richmond, Paul Solotaroff, Charlie Pierce, and Ian Thomspon—who made a splash at the paper. If you've never read her classic piece “The Making of a Goon,” do yourself a favor and check it out.

Howard was in fine form when she visited the Celtics' inimitable master builder as his career approached the finish line. Please enjoy “But Can Red Auerbach Ever Really Let Go?”, reprinted here with the author's permission,

—Alex Belth

So it’s come to this? Larry Bird is almost incommunicado, irked by the Boston media’s suggestion that the Celtics trade him to hasten the rebuilding of the team. Unwanted Dennis Johnson, now 30, keeps stumping for a new contract while Celtics management—pretending not to hear—awaits word from expatriate point guard Brian Shaw.

Kevin McHale’s agent says McHale is thinking of buying a stake in a Minnesota brewery—a sure sign that McHale, now 32, is either distraught from all those trade rumors or pondering serious life after sports concerns. And recently fired Boston coach Jimmy Rodgers is showing signs that his sense of humor is coming back. The revival occurred in late May, sometime between Celtics patriarch Red Auerbach’s hiring of former Big East commissioner Dave Gavitt as the Celtics new “day-to-day basketball man” and the ham-handed handling of the Celtics’ flirtation with Duke University head coach Mike Krzyzewski.

It was about the time longtime Boston assistant coach Chris Ford summed up the chaos in which the organization found itself, likening it to “As the World Turns.” Then Krzyzewski suddenly withdrew from consideration and cleared the way for Rodgers's friend Ford to become the Celtics’ head coach. And almost immediately, callers to Rodgers’s Boston home were greeted by a new answering-machine message that began with the strains of an aria and finished with a voice that said, “I guess it’s over. The fat lady has sung.”

It was meant as a joke. But neither chaos nor comedy was really what Auerbach had in mind when he decided to pass the reins to Gavitt after 40 years as the engine who made the Celtics go.

***

Sitting in his office in the Celtics’ new corporate headquarters in Boston, Auerbach is reflecting on the coverage the Celtics’ wooing of Krzyzewksi received. Reflecting is too mild a word. Auerbach regarded the controversy as grating. Scurrilous. Even insulting. At moments like this, Auerbach does not sound like a grandfatherly man segueing into semi-retirement; he’s still the guy who’s been known to clamber down from Loge I, Row 7, Seat 1 at Boston Garden and chase a ref all the way to the dressing room at halftime, barking up his back.

“Take this rift, rift, rift thing—what rift?” Auerbach growls, sitting behind his desk and biting down hard on his cigar. Black-and-white photographs of past stars and a huge collage of Auerbach during his coaching days peer down from the wall. A six-foot color photo of Auerbach, mounted on foamboard. stands in one corner of the room, across an expanse of green carpet. Cigar ash flecks his cluttered desktop, and copies of the four books Auerbach has written tilt this way and that on a bookshelf to his left. On one corner of his desk, a wooden box as big as two phone books holds Auerbach’s preferred Hoyo de Monterrey cigars. And Red is rolling now:

“There has never been a semblance of a rift between me and Dave. Not a semblance! Dave Gavitt and I are very good friends. But after he joined us, somebody in North Carolina was irate, probably that we dared to have discussions with Mike Krzyzewski of Duke, and this guy wrote that the reason Mike didn’t take the job—which was never offered to him at all; all we were doing was discussing it and, sure, he was a prime candidate and all, but no job was ever offered to him—but anyway, this guy writes the reason Mike didn’t take the job was this so-called rift. Which is absolutely stupidious. Stupid! He said he got it from an authorized source. Bull.

“It just bugs you—it bugs you—that you gutta read that crap… you know what I mean? This… this… yellow journalism! That’s what it is.”

To Auerbach, it was bad enough that he and Celtics co-owners Alan Cohen and Don Gaston looked at their recent problems and decided to fire Rodgers, a longtime loyalist, just two days after the Celtics galling first-round playoff loss to the New York Knicks. Loyalty is one of Auerbach’s most basic tenets.

But perhaps more painful, at least as a reflection of how far the Celtics have fallen, was the unholy way the playoffs ended for Boston—with the Knicks winning a Game 5 showdown on the Celtics’ own parquet floor. If there was ever any doubt the Celtics’ dynastic reign was long past, the funereal mood in the Boston locker room afterward removed it. When the writers and mini-cam mob burst in, they found New England’s storybook heroes slumped on their stools and talking like old age had caught up with them at long last.

“It’s gonna take a long time for this hurt to go away,” Bird said, thinking back to the Knicks’ rebound from an 0-2 series deficit.

“Changes are going to be made,” McHale said.

But with the Celtics’ empire teetering, Auerbach moved more forcefully than he has in years to control the damage. He insisted the team didn’t have to he broken up to be competitive next year, just “refined around the edges.”

Then Auerbach went out and landed Gavitt, the founder and guiding spirit of the Big East. Hosannas rained down on Auerbach, lauding his shrewdness and selflessness.

Auerbach says he recognized the Celtics’ need for a full-time basketball man before Gavitt’s hiring even came up. “I’ll be 73 soon,” Auerbach reminds you. “Your body gets tired, you know? It’s not that I’ve lost any toughness. I just don’t have that old zing. I’m lucky that I still have all my senses—really. And I don’t kid myself that I can come up here [from his long-time home in Washington, D.C.] and spend that much time here anymore, or get on the phones, talk to all these GMs, set up a scouting program, work with the coaches, and be here to talk to the players when they need someone to go to—and believe it or not, the players do like to sit around and talk about basketball. It’s important for them to have someone they know will be here day after day after day.”

***

Though there have been other easily identifiable shifts in Celtics history, Auerbach’s decision probably marks the first time a new Celtics era wasn’t begun by an on-court star.

Usually when people speak of the Celtics’ past, they refer to three golden stretches: the 11 championship years that began with center Bill Russell’s arrival in 1956 and extended three years after Auerbach’s move from head coach to GM in 1966; the NBA titles in 1974 and 1976, during the Dave Cowens-John Havlicek years; and then the success Auerbach ensured with his farsighted selection of Bird in the 1978 draft (a year before Bird left Indiana State) and a larcenous trade: the swap of the Celtics’ No. 1 pick in the 1981 draft for Golden State’s Robert Parish and the Warriors’ No. 3 choice overall, which Auerbach used to grab McHale.

As the cast on the floor changed. Auerbach remained the Celtics’ one constant and as time went on, he carne to symbolize everything people loved or loathed about the team. If Auerbach’s habit of lighting a victory cigar wasn’t reviled—“It’s about as arrogant an act as you can imagine in team sports,” Boston great Bob Cousy once said—then he was accused of getting preferential treatment from the officials, or cranking up the Garden’s intolerable heat. The mere mention of Auerbach’s name was enough to raise hackles on rivals’ backs.

“The truth is, it’s hard for me to be what l was years ago,” Auerbach says getting up and walking across his office toward the collage. He jabs an old photograph of himself. In the picture, his hair is disheveled. A celebration scene is unfolding behind him. Dark circles hang like bunting under his eyes. “That’s me when I got out of coaching in 1966 at the age of 48—and damn right, I look better now than I did then. You've got to be realistic and I’ve always been realistic. I’ve always thought this is a young man’s game. Nowadays we have eight people doing what I used to do by myself then. And maybe they do it better. But how much? When we used to play games on Wednesdays and Fridays, I’d hold practice Thursday morning, then take a plane down to New York or Philly to scout some game, then catch the midnight train so I could be back the next day to work with the team. I didn’t have any assistants, scouts, no travelling secretary. Now, everything has changed.

“That damn [NBA salary) cap has done more to screw things up than you can possibly imagine,” Auerbach continues. “You can aim for a certain deal, for a chance to make it happen, and then find out it can’t be done because it will put you a few bucks over the limit. You just cannot freewheel like you used to. And I’m not that active anymore, either. I don’t have the repartee, the charisma, whatever you want to call it, of some of these young guys running these teams. I don’t even know some of them.”

Amazing as Auerbach’s last admission sounds for the man who’s been making Boston’s draft picks and trades, other general managers say it’s the truth.

“I think Red is probably the greatest general manager and coach we’ve ever had in this league up to this point,” says Donnie Walsh, now in his fourth season as the Indiana Pacers’ team president and GM. “I’ve read all his books, but I don’t think I’ve ever personally talked to him.”

Even Auerbach’s career-long prescience in player personnel decisions has deserted him in recent years. Auerbach will be remembered most for plucking everyone from Russell to Cowens to Bird and Danny Ainge away from unsuspecting rivals. But the acquisition of Bill Walton for the 1985-86 title season ranks as Auerbach’s last coup. The only major trade Boston has made since 1986 was sending Ainge to Sacramento (and Auerbach’s old pal, Russell) for disappointing Ed Pinckney and muscle-bound backup center Joe Kleine.

If the Celtics weren’t hamstrung by the NBA salary cap when it came to signing free-agents or swinging a blockbuster trade, the Celtics’ veteran stars have played well enough in recent years to forestall any drastic change. And even when other trades were possible, Auerbach has refused to budge from his oft-stated vow that Celtics’ stars should finish their careers on the parquet. As recently as two weeks ago, Auerbach was still insisting that Bird, Parish and McHale were “untouchables” when it comes to trades.

It’s hard to know what to expect from the Celtics in today’s draft. During the NBA Finals, word circulated that Auerbach had thought aloud about asking new Seattle Coach K.C. Jones to swap the second pick overall for Parish, now 36. Even if Auerbach doesn’t trade up from the Celtics’ 19th position in today’s first round, he’ll hope to do better than last year’s two mistakes—choosing Michael Smith of Brigham Young University at No. 13, and knowingly passing on center Vlade Divac to draft Divac’s Yugoslavian countryman, 6-10 Dino Radja, in the second round instead.

Divac, the Lakers’ pick at No. 26, turned out to be the steal of the draft, but Radja was prevented from leaving Yugoslavia by his club team after a protracted legal battle. And what happened concurrently was typical of Jimmy Rodgers’s star-crossed tenure: While Rodgers was away on an off-season fishing trip, the Celtics let Shaw get away, figuring they’d sign veteran point guard Larry Drew instead. Then Drew jumped at a chance to sign with the Lakers. And Smith reported to camp “fat,” in Auerbach’s words, and hurt himself trying to hurry into shape.

“We should’ve taken Divac,” Auerbach admitted.

Or, co-owner Gaston said ruefully during the Rodgers post-mortems: “If I were Jimmy Rodgers, I’d say the front office screwed up as badly as I did.”

***

As welcome, then, as Auerbach’s recruitment of Gavitt has been, the cascade of praise ebbed soon after the courting of Krzyzewski began. Even many people who considered Ford eminently capable of handling the job were intrigued by the possibility of Krzyzewski becoming the Celtics’ coach.

“I was watching that to get a read on what to expect,” says one NBA executive, “but so far they’ve gone the way the Celtics would always go under Red—they stayed within the organization and elevated another guy from within.”

If the Ford hiring raised doubts about Auerbach’s true commitment to change, or Gavitt’s real freedom to make the call, Krzyzewski’s sudden withdrawal following a summit meeting with Auerbach and Gavitt in Washington, D.C., fanned speculation that Auerbach never intended to allow Gavitt to hire a head coach from so far outside of the Celtic tradition.

Though Auerbach emphatically insists the Celtics’ job was never offered to Krzyzewski, plenty of conflicting scenarios were widely reported anyway.

According to the media reports emanating from both Boston and Durham, Krzyzewski backed away because: A) He was concerned about making the transition from college to the pros; or, B) There was a “rift” between Auerbach and Gavitt; or, C) Auerbach’s insistence that any head coach other than Ford would be hired with the understanding that Ford would be retained as the Celtics’ No. 1 assistant.

“That was part of everything,” Auerbach says. “Because either way, we weren’t going to let Chris get away.”

The more time passed, the crazier the scenarios got.

One newspaper reported that Bird had attended a meeting in Washington with Krzyzewski, Gavitt, and Auerbach to bequeath his blessing on Krzyzewski in case he was offered the job.

Gavitt and Ford, while attending the NBA’s pre-draft camp in Chicago, were approached in a hotel bar by a reporter who told Gavitt: “I’ve got a confirmed report that you’ve offered the job to Krzyzewski for $2 million a year"—roughly $1.5 million a year more than any current NBA head coach earns. Gavitt turned to Ford, smirked and said: “If I’m offering anyone $2 million a year, Red Auerbach himself must be coming back.”

Then a Boston TV station reported on its 11 p.m. news that recently resigned Lakers Coach Pat Riley was on a plane bound for Boston and would be named the Celtics’ new head coach the next day. What the station didn’t know was that Ford had signed his new Celtics contract at 10 p.m. that same night.

“The Pat Riley thing was probably the best one,” Gavitt laughs. “They were chasing poor Pat Riley’s name all over town. And, as it turns out, there was a Pat Riley on an incoming plane—it just wasn’t the Pat Riley. But there it was on TV anyway: ‘Pat Riley will be named the next head coach of the Celtics!’ And can’t you just see it? Some poor guy named Pat Riley, 68 years old, selling shoe leather or something, gelling off the plane in Boston, tired as hell from his flight in from the coast, and he’s met by this crew of TV cameramen shouting, ‘Where’s Pat Riley?’ And he’s saying, 'Whaaat?'”

As for that report about Bird, Gavitt says reporters could’ve asked anyone in Washington, D.C. who was out on main thoroughfares of the capital that day.

“When we were done with lunch and ready to go back to National Airport, Red said, ‘C'mon, I’ll give you guys a ride, I got nothing better to do,’ “ Gavitt says with a laugh. “But when we get out to the parking lot, Mike and I see that he’s going to take us right through the heart of Washington, where we’re all likely to be recognized, in this beautiful, gleaming, brand-new, jet-black Saab convertible of his. And not only does he have the top down. On the car are these vanity license plates that shout, in big capital letters, the word CELTICS.

“So there we are, flying down the street with me in the front seat, Mike propped up in the back, and Red, who’s a notorious driver anyway because he never watches where he’s going if he’s talking to you, yelling, ‘Hey, how ya doin’?’ to every guy on every street comer who’s yelling out his name.

“All I could think of,” Gavitt sighs, “was, so much for secrecy.”

***

Heading into the ‘90s, the challenges Gavitt inherits along with the Celtics’ organization are many.

Besides making the decisions on any roster overhaul, Gavitt must now oversee the Celtics’ long-running plans to raze Boston Garden and build a new, skybox-rimmed arena on the same site as Red’s old house of thrills. The Celtics recently bought the radio and TV stations that broadcast their games. NBA basketball is going international and NBA officials describe their product as “big-time entertainment” as often as they refer to it as “sport.” And where a simple title like general manager once suited Auerbach just fine, today’s executives like Gavitt adopt Fortune 500 titles like CEO and issue tautly worded, prepared statements through public relations people when questions pour in about the team.

If Auerbach recognizes such “progress” as inexorable, that doesn’t mean he has to be dragged along with it. When asked at Gavitt’s introductory press conference if Gavitt was his successor, Auerbach winked coyly and said: “Well, he’s younger.”

When asked if the move was intended to prepare the Celts for life after Red Auerbach, Auerbach shot back: “I don’t talk about life after Red Auerbach. I got a lifetime contract. I don’t have any one-year deal—unless you think I’m going to die.”

For the first time since Auerbach arrived in 1950, he’s taken a look at the franchise he built and decided that perhaps the best thing he could do for the Celtics was back away. But you get the feeling it’s not because Auerbach can’t rouse himself from the past; he simply prefers it to the present. And that’s an important distinction.

Auerbach is perfectly happy to sit in his Boston office surrounded by the bits of memorabilia that serve as bookmarks to his past. He has a habit of illustrating his points with anecdotes from the ‘40s or ‘50s. Something as common as a pink message slip sends him spinning back.

A month doesn’t go by, Auerbach says fondly, without a call from Frank Ramsey, the Celtics’ original Sixth Man. Just today, the stack of messages also includes inquiries from Cowens, Nate Archibald and JoJo White about the vacant assistant coach jobs under Ford. He mentions a call from Dick Groat, “who was sort of a protege of mine"—and that reminds Auerbach of a story about Bobby Knight, “who was sort of a protege of mine, too.”

Today’s mail brought a letter from a friend in Yugoslavia who writes: “Dear Red, as you and I enter the autumn of our lives…” And Red Auerbach caresses the line like it’s poetry: The autumn of our lives.

The next minute Auerbach is suddenly grousing about the labyrinthine hallways in the Celtics’ new offices and the two-block walk he has to make now to get from his office to the Garden.

“The [new] setup is nice all right,” Auerbach says. “But it’s too far from the basketball court, you know.” And you understand.

If there’s a reason Red Auerbach makes you feel sad, it’s that he makes you wish you were old, too. He makes you realize there’s something wanting about basketball as big-time entertainment compared to basketball in the time warp that is Boston Garden, where the air always hangs heavy and the crowd howls and the heat gets infernal and it all combines to move visiting players to say, as Isiah Thomas did, “Sometimes you just want to run up to somebody on the street when you’re through and shout, ‘Hey, do you know what just went on in there?’”

Red Auerbach knows. And he’s more than happy to let the CEOs have the future. Wherever the game is still the thing, Red Auerbach already owns the past.