The female nude has been configured in art for centuries. Women’s seductive eyes, coy smiles, and an array of supple breasts appear throughout the span of art history in classic paintings, prehistoric sculptures, and contemporary video installations.

But head a little further south and things get dicey. Whether it’s literally or indirectly depicted, there seems to be a big problem with vaginas with contemporary spectators—even when the penis has been flapping in our faces since the dawning of time.

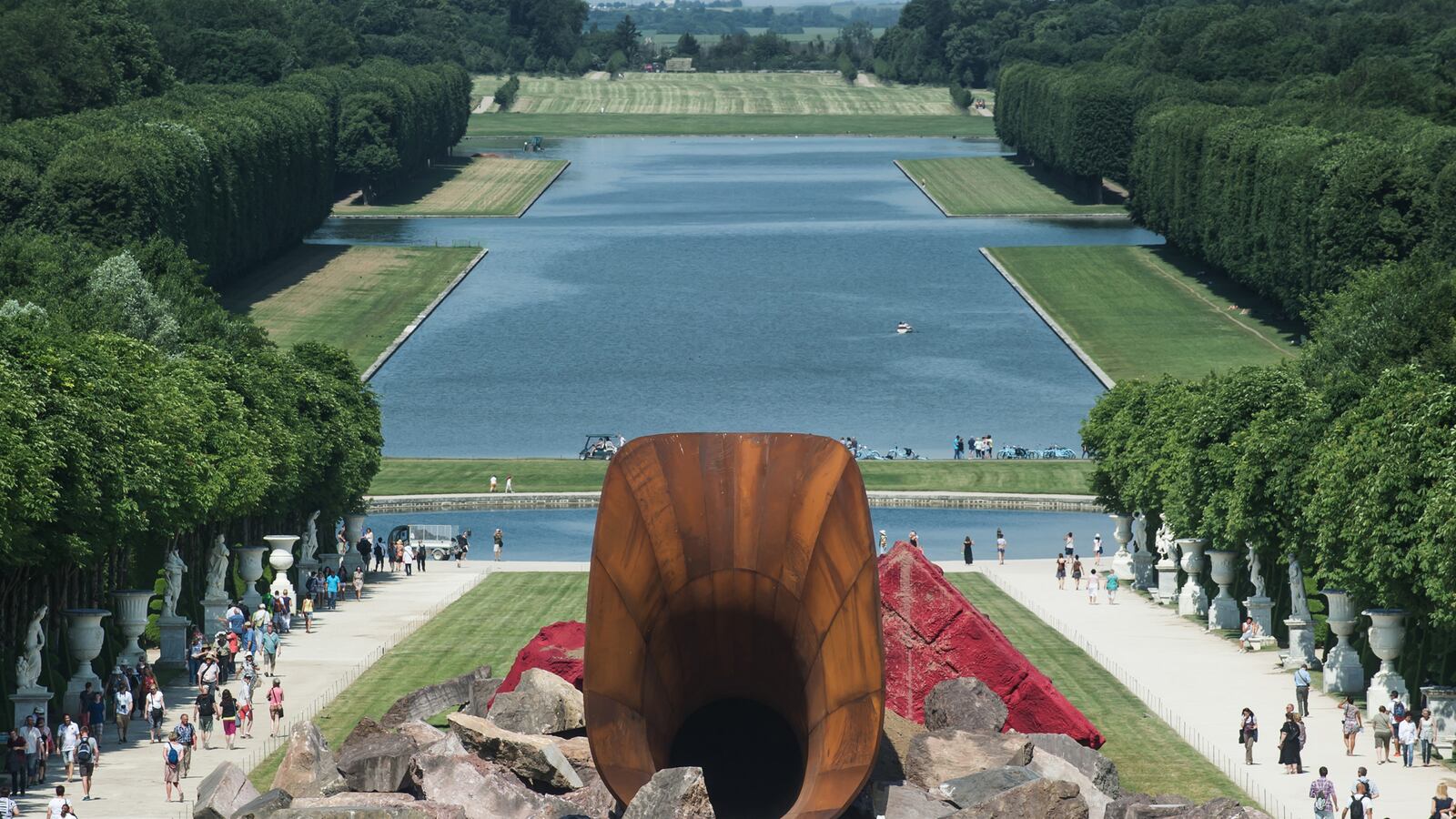

Last week, Sir Anish Kapoor revealed that his recently installed sculpture at the Palace of Versailles, Dirty Corner, was actually a vagina.

Or, as he told French newspaper Le Journal du Dimanche,“the vagina of the queen coming to power.”

He later told the BBC that the “work has multiple interpretive possibilities,” like many of his other pieces.

But until then, no one suspected a thing of the 200-foot tubular steel structure. It’s neither shocking nor provoking as a large, cavernous hole flares open towards the palace from the gardens.

Now, everyone has an opinion.

“When you think you’re coming to Versailles you’d expect like classic French, maybe a big statue of some Roman god, but this just seems dirty, gross,” Megan, a tourist from the United States, told the BBC.

The Guardian’s Michele Hanson is “a bit fed up with this sort of idea of a vagina,” in art. It’s been “done to death,” she says, adding it “is was fairly mainstream to be inspired by vaginas.”

Even the mayor of Versailles, François de Maziéres, tweeted that “Anish Kapor skids on the green carpet.”

Can’t institution and public just get over their vagina problem already?

One of the earliest major vagina controversies to scandalize the art world was Gustav Corbet’s 1866 painting L’Origine du monde or “Origin of the World.”

In it, the painter depicts a very close-up—and realistic view—of the model’s vagina. Her body wasn’t the smooth, idealized figure so common in art at the time, but revealed a natural woman who didn’t wax, laser, or bedazzle her lady bits.

Books have been banned for reproducing the image on their covers and, in 2011 Facebook began blocking accounts of people who posted the photo to their profiles.

One user, Frédéric Durand-Baissas, recently sued the social media site in French court. The outcome could historically change the way social media content is moderated.

Even the same cultural institution in which the painting hangs has had issues when it comes to other interpretations of the culturally lauded work of art.

Last year, artist Deborah de Robertis visited the Musée d’Orsey, where Origin of the World is on view, to re-interpret the piece.

Her version, Mirror of Origin, involved de Robertis sitting in front of the painting and exposing her own vagina.

While a room full of unsuspecting viewers applauded and cheered her act, a team of security personnel quickly tried to block their view of de Robertis while they ushered everyone out of the gallery. She was subsequently arrested.

“This is a typical case of disrespecting the museum’s rules, whether for a performance or not,” the Musée d’Orsay’s administration said in a statement. “No request for authorization was filed with us. And even if it had been, it’s not certain we would have accepted it as that may have upset our visitors.”

It seemed to have only upset the museum, which, along with two guards, filed sexual exhibitionism complaints against de Robertis.

The following month Japanese artist Megumi Igarashi was arrested after distributing computer files depicting a scanned version of her vagina. The “vagina selfies” were sent to supporters of her crowd-funding art project—a kayak modeled on her genitalia.

After a Change.org petition gathered more than 15,000 signatures overnight she was released on bail.

“With this project I wanted to release the vagina from the standard Japanese paradigm,” Igarashi told The Daily Beast after her arrest. “Japan is lenient towards expressions of male sexuality and arousal, but not so for women. When a woman uses her body in artistic expression, her work gets ignored, and people treat her as if she’s some sex-crazed idiot. It all comes back to misogyny. And the vagina is at the heart of it.”

Judy Chicago’s Dinner Party, which depicts 39 vagina-inspired plates and table settings inspired by famous women throughout history, was originally seen as “very bad art,” according to New York Times critic Hilton Cramer, when it debuted in 1979.

It traveled for years before attempting a permanent home at the University of the District of Columbia.

The controversy even reached the House of Representatives, where former Congressman Robert Dornan called it “ceramic 3-D pornography” and Representative Dana Rohrabacher said it was “a spectacle of weird art, weird sexual art at that.”

Chicago retracted her donation and the work has since found a permanent home at the Brooklyn Museum’s Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art.

Then there are those artist-made vaginas that are sexually branded when it was never the artist’s intention at all.

Such was the case with Georgia O’Keefe, whose closely cropped flower paintings have notoriously been associated with the female genital.

They come in various forms and angles in hues so lush and seductive that it’s easy to see the comparison. Yet, she repeatedly dismissed the Freudian association.

Instead, the paintings became highly sexualized by a public perception and a desire to compare something so beautifully simple with a symbol far more complex. The works have become some of the most expensive works of American art ever sold.

In the scope of art, the penis has rarely sparked a massive backlash. They’re painted on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel—one of the most famous religious destinations. They’re included in religious manuscripts from the Middle Ages. And contemporary artists sculpt them by the wall-full without anyone batting an eye.

Only when they are highly sexualized—or unbound by heteronormative constructs—are they historically shunned from the public’s eye. Robert Mapplethorpe, Tom of Finland, and Keith Haring are just a few whose depictions of penises have proved controversial. Only years later, and in memoriam, are they more widely praised for the contributions.

Even Judith Bernstein, a rightly acclaimed feminist artist who has spent most of her life painting various forms of massive, erect penises (as wartime artifacts or massive tools) has had her work banned at exhibitions.

Bernstein has also turned her attention to the vagina.

Her aggressive depictions may seem garish, but they are also generous and unflinching: in their unapologetic blatancy, hope is given to a full acceptance of the female genital. Good for Bernstein and artists like her: It’s about time for us to fully accept the vagina in both life and art, and to be proud to have it on display.