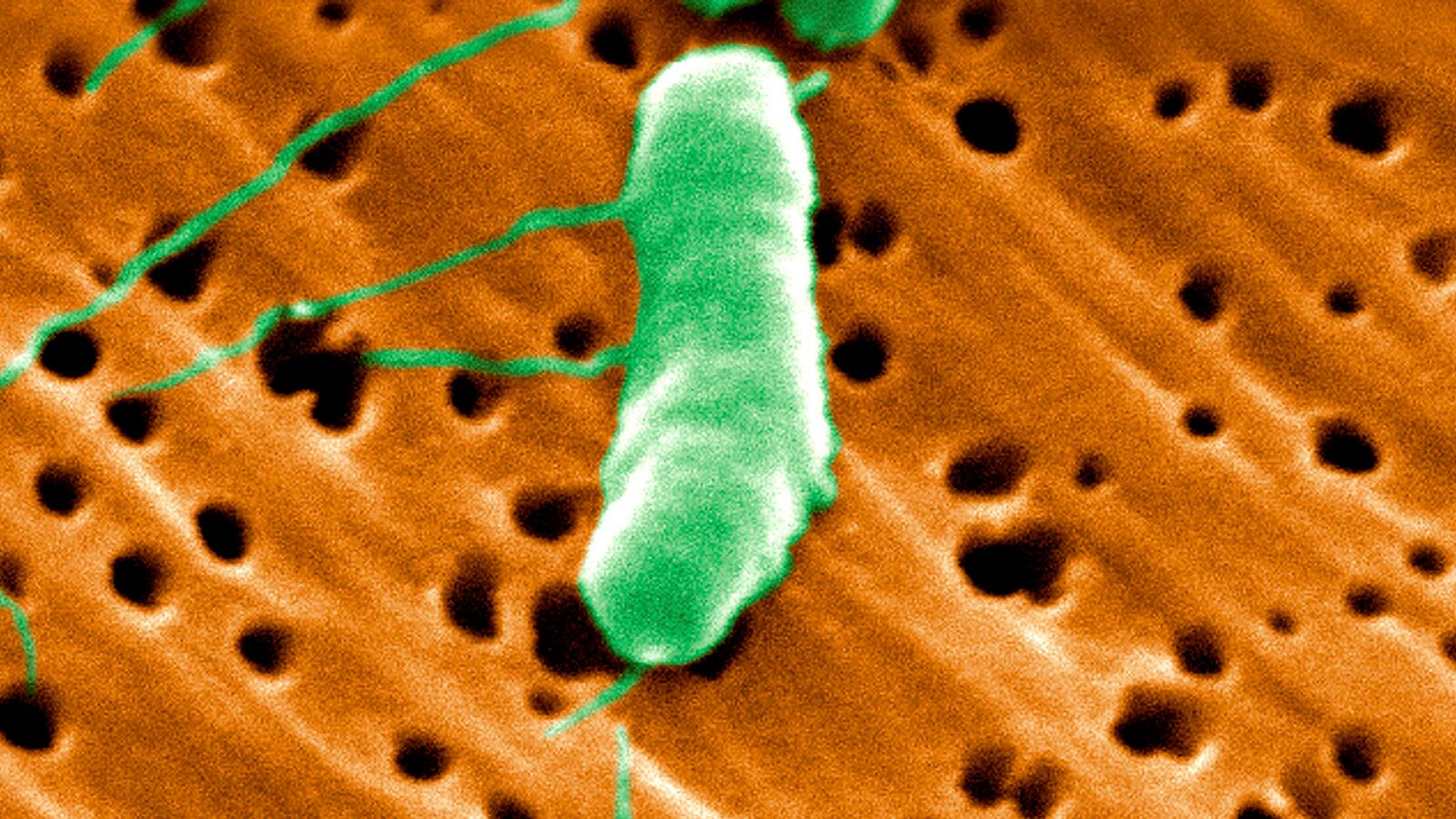

Vibrio vulnificus.

No, it’s not a spell from Harry Potter.

When you think of deadly attacks in the Gulf of Mexico, your mind probably fills with images of toothy sharks. But swimmers on the Gulf Coast have something far more insidious–and hard to avoid–to worry about: Vibrio vulnificus, what’s commonly, though incorrectly, known as flesh-eating bacteria.

While rare, the CDC reports an average of 50 confirmed cases and an average of 16 deaths along the Gulf Coast every year, making death by bacteria far more common than, say, the aforementioned shark attacks.

Most recently, on June 14, 26-year-old Cason Yeager was swimming with his mother in waist-deep water off Pine Island Beach in Florida’s Hernando County. Two days later he was dead at a local hospital. Yeager had been diagnosed years ago with an autoimmune disease, but had been healthy since.

“This has been a nightmare for me, to say the least, and nobody should have to go through this,” Karen Yeager, the victim’s mother, told ABC News.

Yeager was Florida’s fourth fatality from the bacteria this year.

Vibrio vulfinicus is naturally occurring in warm salt water, and enters a victim’s bloodstream through a wound or the gastrointestinal tract, and in fact, accounts for 95 percent of all seafood-related deaths. Once inside, symptoms begin to appear within 16 to 38 hours, and range from “food poisoning” to “horror movie”: vomiting, diarrhea, acute abdominal pain, wound ulceration, tissue death, blistering skin lesions, and primary septicemia, which can lead to septic shock and death. People with immune disorders are potentially 200 times more likely to experience the worst of the symptoms. Vulnificus victims have a 50 percent mortality rate.

Most cases of vulfinicus are treated with antibiotics, though high-risk patients who develop wound necrosis often require amputation.

Eighty-five percent of vulfinicus cases in the Sunshine State occur between May and October, with 32 reported in 2014. The Florida Health Department issued a warning about the bacteria in early June, cautioning people with cuts and scrapes not to swim in the ocean, and urging people to be wary of undercooked, and avoid raw, shellfish.

Vulfinicus occurs even in clean seawater, but in Texas health officials have been warning swimmers to avoid Gulf beaches since the recent flooding has led to water quality being on par with “toilet water.”

Not even pools are completely safe. Recent years have seen a spike in parasitic sicknesses related to recreational treated water, such as pools and hot tubs, which often contain chlorine or bromine to kill bacteria.

“Flesh-eating” bacteria is not just in the ocean or shellfish, either, as 23-year-old Texan mother Brittany Williams found out this month after contracting an infection in her eye during a mud race.

A combination of debris scratching her eye and the petri dish-like properties of a contact lens led to the bacteria destroying her cornea.

“It just completely melted off of my eye,” she told a CBS affiliate in Dallas.

Williams, who does not have insurance, set up a crowd funding page to offset the over $100,000 in medical bills she’s racked up, and is blind in that eye.

In Georgia, Cindy Martinez, a 34-year-old Marine vet and mother of two, had to have her feet and left hand amputated to halt the spread of necrotizing fasciitis. Doctors aren’t sure how Martinez came in contact with the bacterium that causes the infection.

But at least Martinez and Williams escaped with their lives. Karen Yeager’s son wasn’t so lucky.

“I’m not telling anyone, don’t go into the water—just do your due diligence and make sure that you’re not going to harm yourself,” she told CBS.