There are no leg-shaking, pelvis-thrusting ballads being sung at the Coco Palms Resort any more.

Half a century ago, this was the Elvis-anointed vacation hotspot that inspired thousands of glamour-seeking vacationers and starry-eyed newlyweds.

But until today, the resort in Kauai famous for its coconut groves has—over more than two decades—crumbled into disrepair.

Now, after years of fundraising and lobbying, the resort is looking at a big makeover and a return of guests for the 2017 season.

The Coco Palms opened in 1953 with a skeleton staff of four and 24 rooms. Its first night attracted two guests.

But its owners had a plan to bank in on the rich cultural backdrop of the island. Set on the Wailua cast, the resort’s property had been the seat of the island’s royal family for over 600 years.

It was once the home of Kauai’s last monarch in power, Queen Deborah Kapule Kekaiha ‘akulou, who died in 1853. With this in mind, the Coco Palms was billed it as the epitome of exotic Hawaiian tiki luxury.

Rita Hayworth filmed Miss Sadie Thompson (1953) there. Then came South Pacific (1958), and, in 1961, the Elvis blockbuster Blue Hawaii.

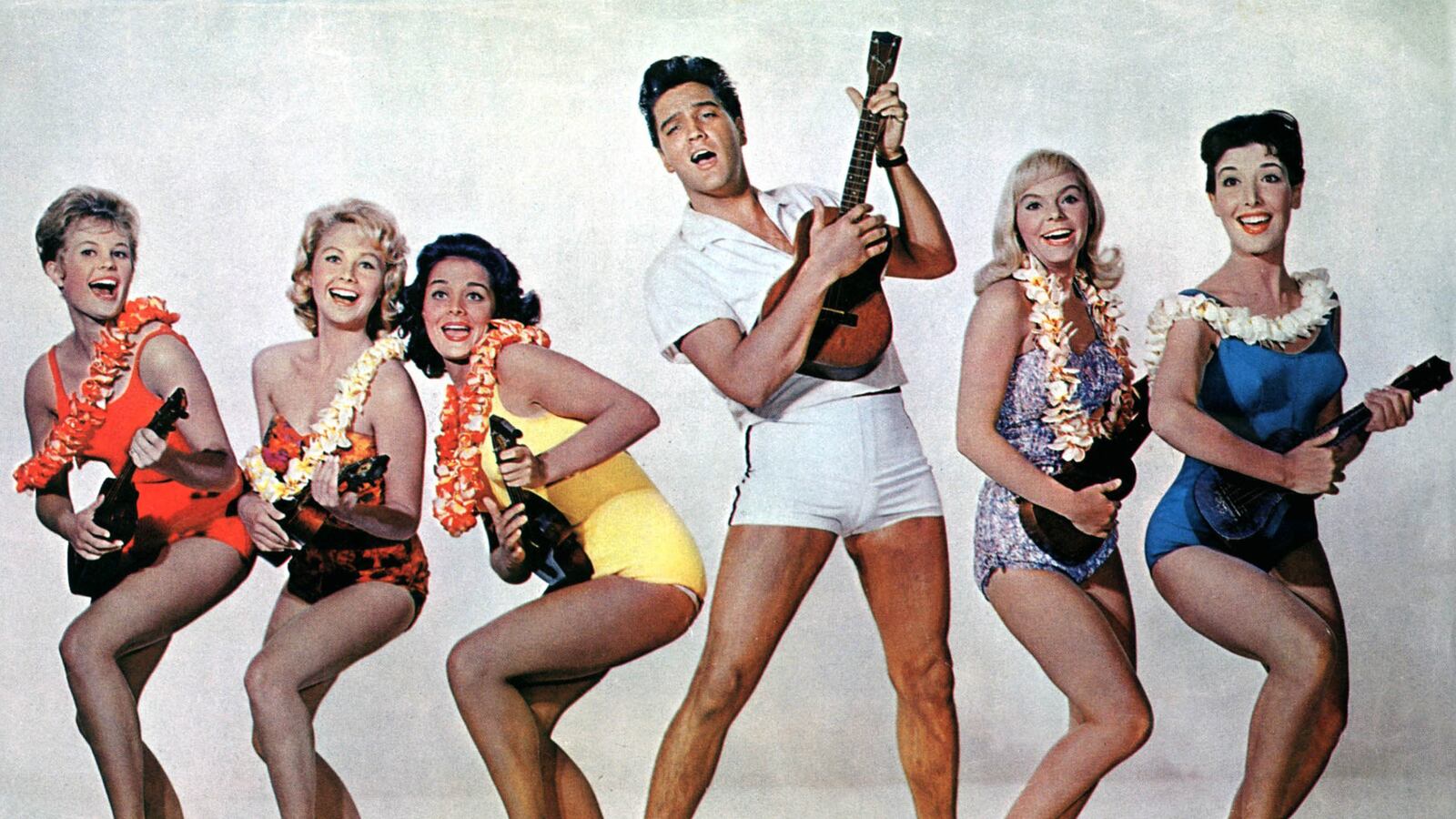

“Exotic romance…exotic dances…exciting music…in the world’s lushest paradise of song!” the film poster promised, luring viewers with its “Panavision technicolor.”

In it, Elvis and his bevy of lei-draped beauties danced on the beach, surfed the crystalline coast, and frolicked among the resort’s coconut groves.

In the most famous scene, Elvis and his leading lady get married on a canoe serenaded by Hawaiian singers.

With its newfound fame, the Coco Palms Resort expanded to more than 400 guestrooms. They were occupied by visitors like Frank Sinatra and the Von Trapp Family Singers.

Hollywood and international royalty flocked to observe the nightly torch-lighting ceremony and dine on exotic menu items.

Elvis’s Blue Hawaii sparked a nuptials craze with longevity. Over the next 30 years, Coco Palms played host to an average of 500 weddings per year.

But in 1992, deadly Hurricane Iniki struck Kauai. It caused an estimated $1.8 billion in damage, and claimed the Coco Palms among its victims. The resort was hit hard, and the owners faced a mess of bureaucracy that halted any rebuilding.

While they argued with insurance companies in court, the weeds overtook the once-grand hotel, and vandals made off with its entrails. Amid the destruction was a key survivor: The cottage where Elvis stayed during shooting, number 56, remained unscathed.

Since the hurricane, the Coco Palms has been bought and sold, surveyed and prospected with little progress on actual reconstruction.

Then last year, Hyatt announced it had agreed to take on the renovations in partnership with Coco Palms Hui LLC, a Hawaii-based firm that has pledged to restore it.

Together, they plan to rebuild 331 guestrooms and 32 bungalows, along with restaurants, pools and lounges—a vision that carries a $125 million price tag.

But luck is not on the resort’s side. Last July, a fire broke out at the Coco Palms and the responding fire crews were forced to demolish the main lobby, breezeway, and adjoining offices.

Despite this setback, work on the resort went ahead as planned.

This spring, the county planning commission green-lit a reconstruction plan that will rebuild the resort and open it in two years.

“This project is in a way, it is not about architecture,” an architect on the project said in March. “It is about respecting and bringing back the culture and history of Coco Palms.”