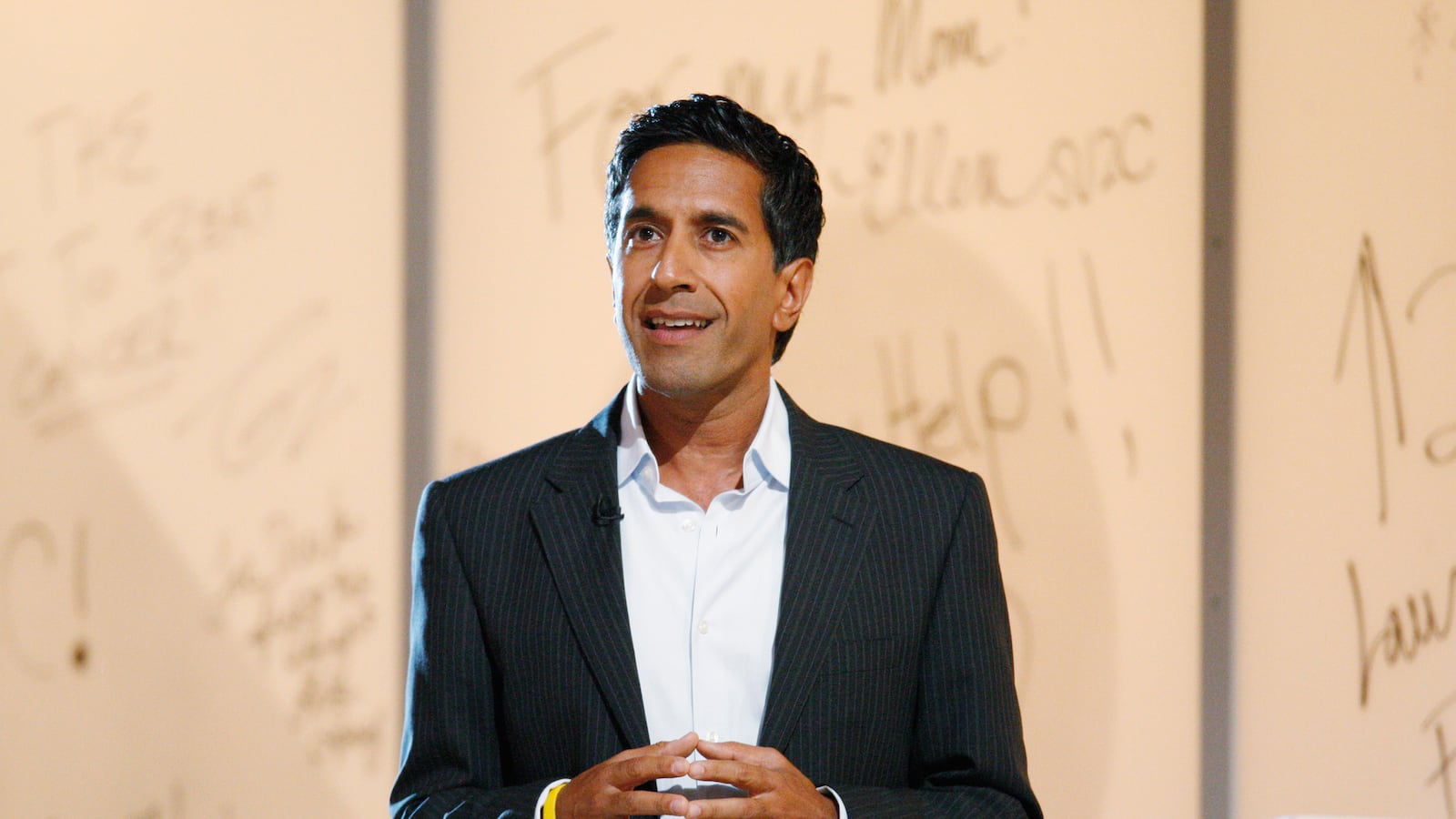

“I hate mistakes. I really hate them,” Sanjay Gupta told The Daily Beast on Wednesday, a few hours after acknowledging the distinct probability of an epic blunder.

CNN’s dashing resident neurosurgeon and chief medical correspondent—who frequently moonlights in operating rooms while on assignment covering wars, plagues, and natural disasters—was doing live reports from earthquake-ravaged Nepal in late April when he helped with a craniotomy on a gravely injured girl.

And then, according to an investigative story posted Tuesday night by the Global Press Journal, the publication of a San Francisco-based nonprofit that supports female journalists in developing-world countries, the cable news outlet’s star doctor/journalist committed a blush-worthy beaut.

Wielding a drill and a string saw used for brain surgery, the 45-year-old Gupta seems to have mistaken one patient for another, and then passed off his error as fact to a global television and Internet audience.

Nobody pointed out the slip-up for months, and Gupta said he believed his journalism was solid until the GPJ’s report credibly indicated otherwise.

The story of Gupta’s gaffe—the result of a tip and weeks of persistent shoe-leather reporting on the ground by Nepalese journalist Shilu Manandhar—has prompted CNN to launch its own investigation to verify the facts (while taking strong issue with elements of Manandhar’s story). Yet the GPJ story, which involved treks to remote areas, locating both of the patients and their families, and gathering reams of supporting documents, clearly performed a valuable service and pushed CNN to correct the record.

“Questions have arisen about the identity of the girl who Dr. Sanjay Gupta helped operate on during a week in Nepal in the aftermath of a devastating earthquake,” the network said in an editor’s note posted Wednesday on its website. “CNN is looking into those questions and will update our coverage as warranted…”

The embarrassing circumstance has also obliged Gupta to undergo painful introspection.

“I take this very seriously,” he said in a phone interview. “We’re going to learn from it. I’m going to continue to dissect it. I’ve thought about nothing else, frankly, since they first flagged this for me on Tuesday, and I’m going through everything. I’ve been on the phone constantly with my team… If there’s a lesson to be learned, I’ll certainly share that.”

Influential media critic David Folkenflik of NPR, whose early piece on the controversy in the wee hours of Wednesday certified its significance in the newsbiz, said it highlights the phenomenon of celebrity doctor/television correspondents who stop practicing journalism as neutral witnesses of news events in order to practice medicine as central characters in their own reports.

“Are they there on behalf of the public’s right to know or on behalf of the Hippocratic Oath?” Folkenflik asked. “I don’t necessarily see those two things in conflict, but the question is, do you make a story out of that, and to what degree do you really have to be the star of your own story? When you get a story like that wrong, it doesn’t just double these questions, it kind of geometrically increases them.”

Needless to say, at a moment when the Brian Williams fiasco and other recent failures have already threatened the public’s trust in the TV folks who deliver the news, Gupta’s high-profile blooper does nothing to enhance that confidence.

The CNN team arrived on the chaotic scene in Nepal amid an overwhelming influx of quake victims at Bir Hospital in the capital, Kathmandu, a couple of days after the mountainous kingdom had been rocked by a devastating 7.8-magnitude temblor on April 25.

Soon after they reached the hospital, Gupta announced to viewers that he had just helped staff doctors perform emergency surgery on an 8-year-old Nepalese girl with a potentially lethal head injury. But the problem, according to the GPJ’s exhaustive report, is that the patient on the operating table was actually a 14-year-old female quake casualty from a completely different town.

Worse, CNN had initially reported the patient’s age, identity, and condition more or less accurately in an April 27 web story by digital producer Tim Hume. The story had her name right, but, in a minor error, added a year to her age, saying she was 15 instead of 14.

Yet nine hours after that story was posted, Gupta big-footed Hume and had the report altered to reflect—erroneously, according to the GPJ—that he’d operated on the 8-year-old. Ironically, Gupta believed he was correcting a mistake. (According to a CNN spokesperson, the wholesale write-though and update—in which the 14-year-old’s medical condition was simply ascribed to the 8-year-old—were briefly noted on the Web, but as typically happens the note was eventually scrubbed, leaving CNN.com readers none the wiser.)

The next day, Gupta broadcast several reports featuring the bandaged 8-year-old girl, whose injuries (a broken wrist, facial bruises, and head wounds, as accurately described in CNN’s original web story before Gupta changed it) didn’t actually require surgery, along with the girl’s traumatized grandfather, who, colorfully enough, wore traditional peasant garb.

On the phone from Kathmandu, Gupta told New Day anchor Alisyn Camerota, over video of 8-year-old Salina Dahal on a gurney, that she’d sustained a skull fracture and a blood clot on her brain.

A second CNN video, according to the GPJ, showed Gupta examining a CAT scan while the tiny, frail-looking Salina sat on a nearby stretcher. “Examining her CAT scan reveals just how dire her situation is,” Gupta narrated. “She has a fractured skull, a blood clot, and her brain is swelling…Without emergen[cy] surgery, she’ll have permanent damage. Or, like so many other earthquake victims, she’ll die.”

Then, according to the GPJ’s report, Gupta appeared onscreen wearing surgical scrubs in an operating room, after which he was shown declaring the surgery a success.

“Salina will live,” he intoned.

But the patient on Gupta’s operating table, the GPJ reported, was not Salina at all. It was actually 14-year-old Sandhya Chalise, from the suburb of Ramkot, less than 10 miles from Kathmandu, not Salina’s remote village of Dahal Tole, a three-hour journey from the Nepalese capital.

Gupta, who had once been touted for U.S. surgeon general by the Obama administration, has been toiling at CNN for 14 years and teaches at Atlanta’s Emory University School of Medicine while regularly performing brain surgery at Grady Memorial Hospital, where he is associate chief of neurosurgery.

So how could this Emmy-winning, impressively credentialed physician/journalist, whose ability to succeed at dual careers depends on precision, have messed up so badly?

“There were hundreds of patients in the sitting area, which was essentially the lobby of this hospital, and there were six children with brain injuries,” Gupta explained. “Only two of them were teenagers, and they all looked like they were young kids. And the hospital staff was telling me who these patients were and showing me the patients’ scans, and giving me all this information.”

Noting that he doesn’t speak Nepali and there may have been “language challenges,” even though many of the doctors seemed to speak competent English, Gupta recalled examining the CAT scans of both 14-year-old Sandhya and 8-year-old Salina.

“They had very similar injuries,” he said. “When you talk about head injuries in this sort of setting, it usually comes from some sort of blunt force to the head, something falling on you in an earthquake. So an epidural hematoma, which is a blood clot on the brain, is a common injury. Those girls both had right-side-of-the-brain epidural hematomas.”

Gupta continued: “When I went into the operating room—the surgeons came and grabbed me, they said they were not going to start the case until I was in the operating room—the patient was already draped. So when you walk into a situation like that, the best way I can describe it is all you really see is the top of the head.

“You wouldn’t even be able to tell with conviction how tall somebody is. Everything else is draped. The operating table was full of instruments that were over at the end of the table. So it would have been very challenging for anybody to say, after the patient was already draped, how old a patient was.”

Gupta said the hospital staff had given him the information on the patient’s identity, and he had no reason at the time to doubt it.

Gupta said Bir Hospital was overwhelmed, and he could hardly refuse when staff physicians—who apparently knew that he was a neurosurgeon “from television”—asked him to lend a hand in a craniotomy, the removal of part of the bone from the skull to expose the brain and relieve potentially lethal swelling.

The GPJ story, however, quotes Rajiv Jha, identified as an “accomplished neurosurgeon” who presided at the surgery, as saying that it was Gupta who asked to be in the O.R., not the other way around.

Jha claimed he was resistant to Gupta’s alleged request.

“I met him in the morning,” Jha is quoted as saying, “Since the morning, he wanted to help me during surgeries… But, as I said, that I have sufficient manpower to perform the neurosurgeries.”

In his interview with The Daily Beast, Gupta vigorously disputed Jha’s claim that he basically begged his way into the surgery—which is presented unchallenged in the GPJ story, although there was good reason, as the story later implies, to question Jha’s credibility.

“A hundred percent, they asked me,” Gupta said. “This goes under the bucket of ‘No good deed goes unpunished.’ There are a lot of shocking things in that Global Press piece. But in some ways, that was the worst part of it. Because they asked me to help them, they knew I was a neurosurgeon, they were very busy with six patients, six children, waiting for operations. I fully understood why they would be asking for help. And I was happy to.”

Gupta added: “Frankly, within an hour after getting there [at Bir Hospital], I was in the operating room. That’s how quickly things moved along. But then I read in the article that Jha said, ‘Oh, he’s been asking me since morning, and I finally let him in.’”

In the GPJ story, Jha also claimed that Gupta “merely observed in the surgery, and briefly used a suction tool to examine Jha’s work”—a claim that was proven to be demonstrably false, and should have given the GPJ pause concerning Jha’s motives and whether he was prone to shade the truth in the service of ego, jealously, internal hospital politics, or some other undeclared interest.

Jha’s apparent campaign against Gupta began four days after their collaboration in the operating room. A May 1 story in the Kantipur News, Nepal’s biggest Nepali-language news outlet (an English translation of which was provided to The Daily Beast by CNN), quoted Jha as making the same questionable claims highlighted in the GPJ story.

Although digital producer Hume declined to comment to the GPJ, and CNN didn’t make Gupta available to give his version of events, which instead was communicated by a CNN spokesperson, the cable outlet provided raw, unaired footage “showing Gupta in the same operating room with Jha, using a hand-operated drill, a string saw, and other tools,” the GPJ story reported.

Yet the article allowed a hospital administrator to impugn Gupta’s professionalism without a response from CNN:

“A good surgeon knows the identity of the patient he’s operating on,” says Ganesh Bahadur Gurung, vice chancellor of Nepal’s National Academy of Medical Science, which manages Bir Hospital. A doctor who drills into a patient’s head without confirmation of the patient’s identity “is not a surgeon, he is a butcher,” Gurung says.

“Yeah, I know, that’s shocking to me,” Gupta said with a sigh about the “butcher” comment. “I don’t know. I don’t engage in personal attacks. We’re all professionals here at the end of the day. I operated on a girl and she’s doing well. I don’t know how he reconciles that with being a ‘butcher.’ That’s very hurtful as well. I was hurt by this.”

The Kantipur News story—which was not cited by the GPJ—quoted hospital administrator Gurung as attacking Gupta (per the CNN translation): “This is the height of irresponsibility as a journalist… He has tried to show himself a hero by preparing a video that shows as if he is performing a surgery. I have warned him.”

Gupta told The Daily Beast that he has never met or spoken with Dr. Gurung.

A CNN spokesperson, meanwhile, pointed out that the GPJ’s story omitted facts that would have painted a picture of general confusion at Bir Hospital and alerted readers to the likelihood that Gupta’s mistake was an honest one made in a fast-moving, frenzied environment.

For instance, the story didn’t report that the hospital initially claimed inaccurately to the GPJ that no juvenile earthquake victims had undergone neurosurgery, and a handwritten patient intake sheet photographed by digital producer Hume initially identified the 14-year-old that Gupta treated, Sandhya Chalise, as a 26-year-old female.

Cristi Hegranes, founder and executive director of the GPJ and the Global Press Institute nonprofit, stoutly defended the story to The Daily Beast, including the use of questionable assertions from Jha and Gurung.

“It’s super-clear—we don’t rely on the doctors at all,” Hegranes said. “We pushed the hospital very hard… doing the interviews dozens of times. We found the girl, copies of medical records, and got statements from her family.”

Asked if there was anything she would have changed in the story, Hegranes responded: “I would have loved the opportunity to talk to Sanjay Gupta. But when a small international news organization and nonprofit asks, he instead talks to NPR, which did the story for five minutes. If CNN had issues about our reporting, for which they had seven days to respond, that was a choice they made. I’m sure they were hoping we would go away.”