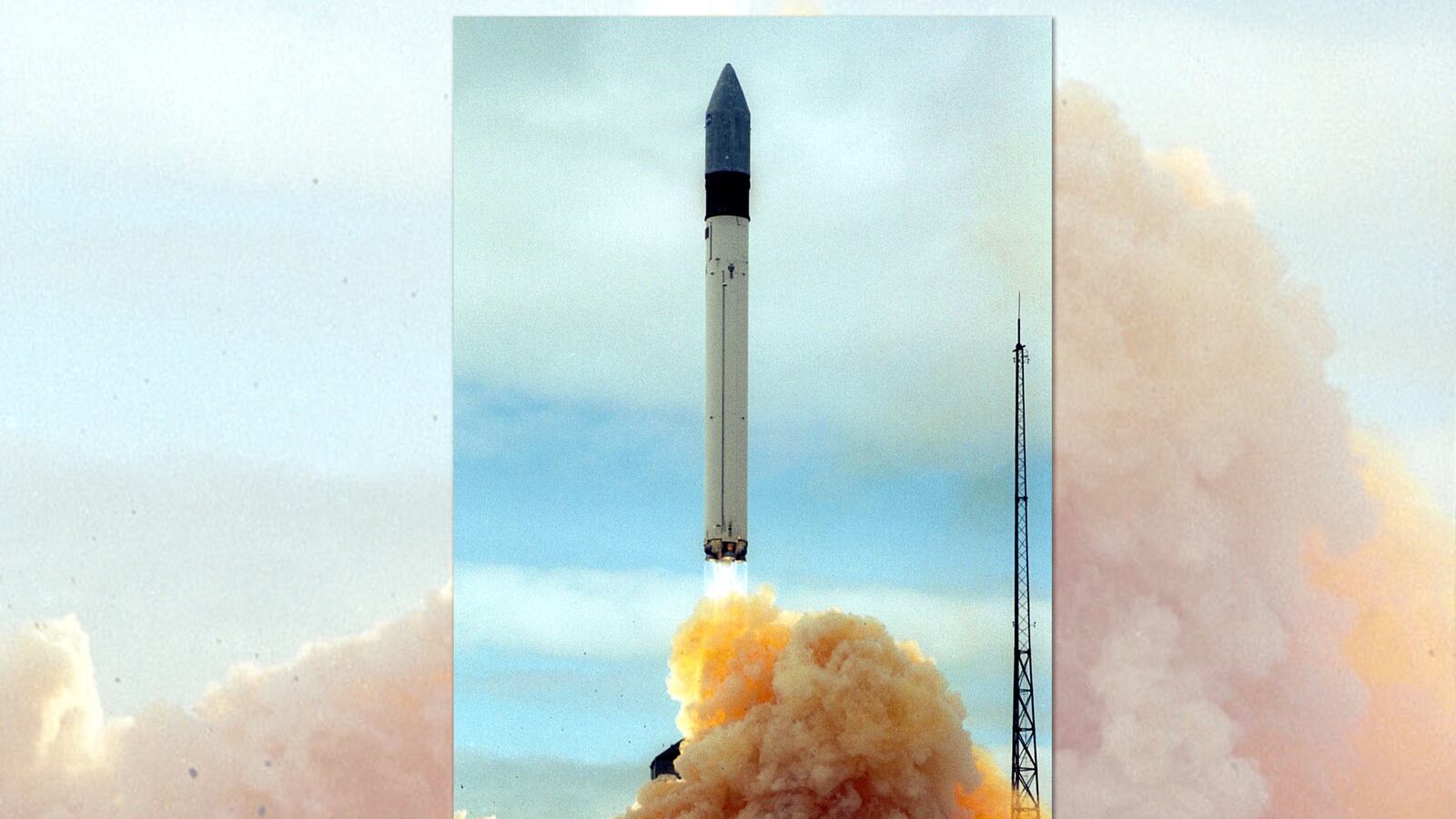

On Christmas Day in 2013, a rocket blasted off from the Russian Federal Space Agency’s Plesetsk Cosmodrome, about 500 miles north of Moscow. The 95-foot-tall, 118-ton Rokot booster—an unarmed version of a Cold War nuclear-tipped missile—lanced into low orbit, shedding spent stages as it climbed.

Seventy-five miles above the Earth’s surface, the Rokot’s nose cracked open and its payload spilled out. The rocket carried Rodnik communications satellites, according to Russian officials.

It’s customary for Rodnik sats to deploy in threes, but in a notification to the United Nations, Moscow listed four spacecraft inside the Christmas Rokot.

The discrepancy was strange...and got stranger.

Rodnik sats, like most orbital spacecraft, don’t have engines and can’t move under their own power. So it came as a shock to some observers on the ground—a group including amateur satellite-spotters with radios and telescopes; radar-equipped civilian researchers; and military officials monitoring banks of high-tech sensors—when the Rokot’s fourth satellite, designated Kosmos-2491, moved, propelling itself into a slightly different orbit.

Whatever Kosmos-2491 was, it wasn’t some innocuous communications satellite. And over the next year and a half, Russia launched two more of the mysterious, maneuvering spacecraft, each time sneaking it into orbit as part of a routine commsat launch.

No one outside the Russian government, and perhaps the Pentagon, knows for sure what Kosmos-2491, -2499, and -2504 are for. But it’s clear enough what the three mystery sats could do, in theory. Zipping across orbital planes hundreds of thousands of feet above Earth, the nimble little spacecraft—which are apparently the size of a mini-refrigerator—are able to get really close to other satellites. Close as in a few dozen feet away.

And if they can get that close, the little robots could spy on, hijack, and even destroy other sats.

In other words, Kosmos-2491 and its triplets might be space weapons, the likes of which few other nations possess. And if so, they could upset the orbital balance of power, at a time when government agencies, armies, scientists, and everyday people—in the United States, especially—depend on satellites for communications, surveillance, science, and navigation.

“Our nation’s advantage in space is no longer a given,” U.S. Air Force General William Shelton, then head of Air Force Space Command, told Congress in March 2014. “The ever-evolving space environment is increasingly contested as potential adversary capabilities grow in both number and sophistication.”

Space Sleuths

Kosmos-2499 joined Kosmos-2491 in low orbit on May 23, 2014, piggybacking on another cluster of three commsats. Kosmos-2504 made its debut on March 31 this year—again, boosting into space alongside a trio of communications satellites.

The three mystery sats have stayed busy, firing their tiny engines to climb and dive hundreds of miles at a time, altering their velocity by hundreds of feet per second while playing chase with abandoned rocket stages and other hunks of space junk, apparently practicing for close passes on active satellites.

The U.S. military has watched all these maneuvers carefully. “As we do with all space objects—for space situational awareness purposes and to promote safe and responsible space operations—we are using our global network of sensors to watch Kosmos-2491, -2499, and -2504,” said Captain Nicholas Mercurio, an Air Force spokesman.

But the Pentagon won’t say exactly what it thinks the satellites are for. Nor, of course, will the Kremlin specify the crafts’ purpose. In a brief statement in December, Russian Federal Space Agency chief Oleg Ostapenko insisted the mystery sats were peaceful in nature and not, as outside observers feared, “killer satellites.”

But Ostapenko did not specify what supposedly peaceful purpose the craft do serve. And since then, Moscow has kept silent about the satellites. The Russian space agency didn’t respond to an email seeking comment.

Undeterred by the lack of official comment, an international band of space nerds has taken it upon itself to solve the mystery of the three nimble spacecraft. In the summer of 2014, Russian radio enthusiast Dmitry Pashkov detected signals that he eventually traced back to Kosmos-2499.

Fellow radio aficionado Cees Bassa, who is Dutch, picked up similar chirps from the direction of the other mystery sats and connected the dots. “I was one of the first to confirm that the recent Kosmos-2504 satellite was transmitting on the same frequency as Kosmos 2491/2499, confirming the similarity between them,” Bassa said.

Uniting the space sleuths is Anatoly Zak, a Russian-born journalist and self-described “space historian.” Now living in the United States, Zak aggregates observations of Kosmos-2491 and its siblings at his website, Russianspaceweb.com.

Combining all the evidence, Zak concluded that the mystery craft are all similar in size and shape to Russia’s 200-pound Yubileiny experimental satellite—and are most likely weapons. “You can probably equip them with lasers, maybe put some explosives on them,” Zak said of the Kosmos triplets. “If [one] comes very close to some military satellite, it probably can do some harm.”

And even if the mystery sats aren’t armed themselves, they could be prototypes for bigger and better follow-on spacecraft that are armed, Zak added. “Looking at the history of space technology, it often starts with a small and cheap satellite that’s easy to launch, then the same technology gets incorporated into something larger.”

Late to Orbit

To be clear, if indeed the Kosmos triplets are weapons, they’re certainly not the only ones in Earth orbit. The United States, Sweden, Japan, and China have all tested maneuvering satellites that could perform the close-flying, sat-frying tricks that the new Russian craft are apparently capable of doing. It’s all being done in the name of satellite maintenance and repair. But the same tech can be deployed for more aggressive purposes.

The U.S. Air Force launched two Geosynchronous Space Situational Awareness Program satellites in July 2014. These sats “will have the capability to perform Rendezvous and Proximity Operations (RPO),” according to an Air Force website. “RPO allows for the space vehicle to maneuver near a resident space object of interest.”

Just like the Kosmos triplets can do. The big difference is where the U.S. spacecraft are—30 times higher than the Russian crafts’ low orbit. Boosting a satellite to such a lofty orbit is “much trickier, technically” but conveys big advantages, according to Dr. Laura Grego of the Union of Concerned Scientists, based in Massachusetts.

For one, geosynchronous orbit is where the most valuable communications satellites are. If you want to threaten another country’s orbital infrastructure, that’s the best starting point. Moreover, the lofty orbit gives the situational-awareness sats “a clear, unobstructed and distinct vantage point for viewing resident space objects,” the Air Force website explains. In other words, these spacecraft can keep an eye on other spacecraft—potentially including weaponized craft such as the Russian mystery sats.

In launching the secretive Kosmos-2491, -2499, and -2504, Russia is playing catch-up, in a sense. The United States tested its first satellite-killer way back in 1962—albeit inadvertently. The Starfish Prime nuclear test, which exploded an atomic bomb 250 miles over the Pacific, had the unfortunate side effect of knocking out a full third of the satellites then in orbit. Today U.S. Navy destroyers carry SM-3 missiles that can hit spacecraft in low orbit.

But from the American point of view, it’s still highly provocative for Moscow to deploy potential space weaponry. That’s because more than any other country, the United States counts on its spacecraft to maintain a military and economic edge.

America’s satellites spy on the ground and sea, support vital scientific research, and relay radio messages including the signals that control drones and help soldiers—not to mention millions of commuters—find their way via GPS. Of the world’s roughly 1,200 active satellites, nearly half are American, while Russia and China each possess a 10 percent share of orbital hardware.

Ironically, that means America is also “more vulnerable” in space, Grego said. The United States offers up more satellites as targets and arguably needs those sats more than other countries need their own spacecraft. Grego said the only way to preserve orbital peace is for no country to deploy space weaponry: “It does not benefit anyone to pursue completely unfettered development of anti-satellite technology.”

But it’s probably too late for total orbital disarmament. The trend is toward more military assets in space—and more anti-satellite systems. In 2007, China pissed off governments all over the world when it blasted one of its own defunct satellites with a rocket, scattering thousands of shards of metal across low orbit and endangering countless active spacecraft.

And when Russia quietly boosts three highly maneuverable and potentially armed spacecraft into orbit and then declines to explain their purpose, it’s sure to keep U.S. military officials awake at night, staring into the night sky, wondering just what the fleet-footed little Russian robots are up to...and how they might counter them.