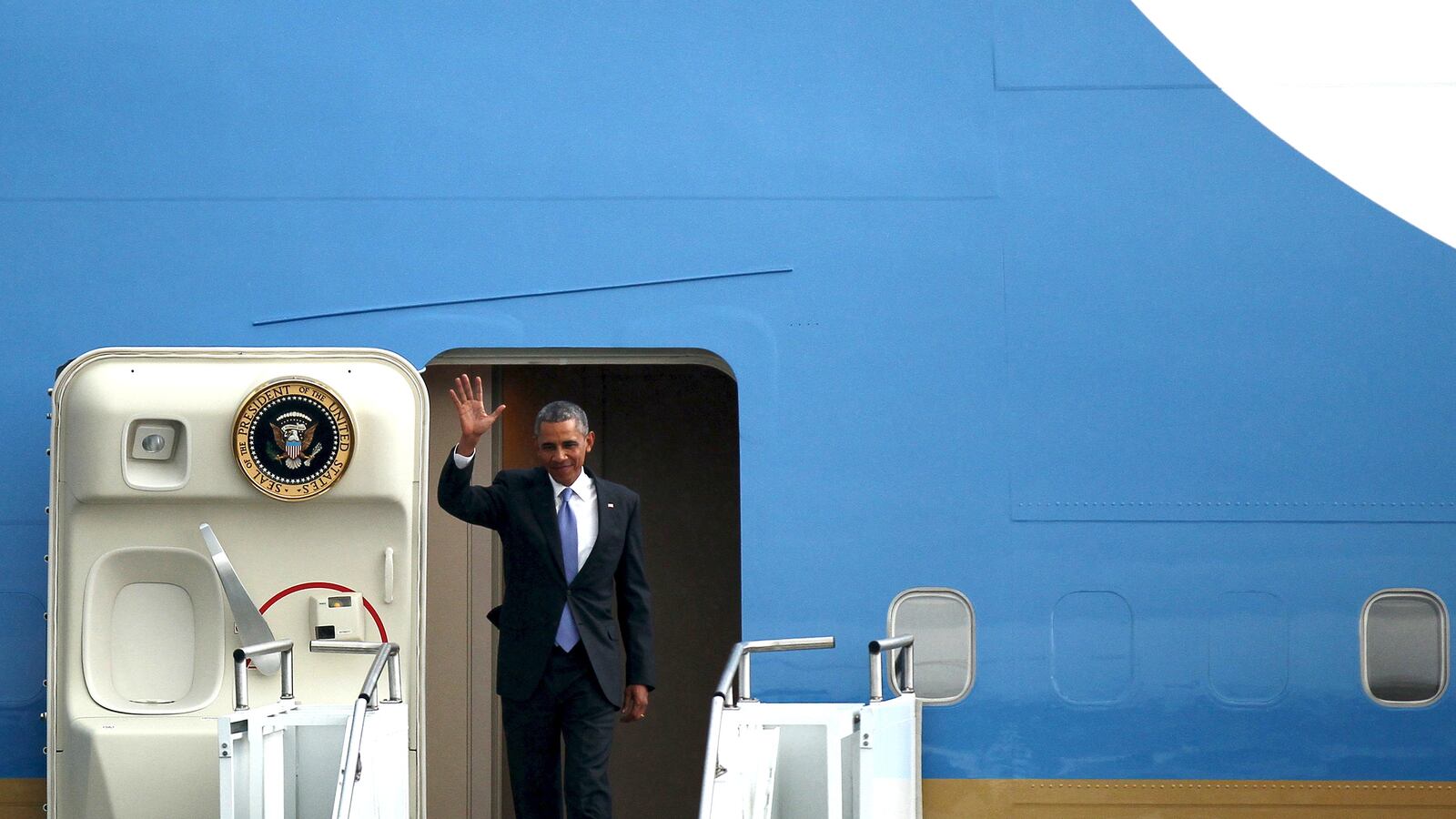

NAIROBI — In what may give the term “birther” new meaning, it’s rumored that in Kogelo, President Barack Hussein Obama’s father’s hometown on the shore of Lake Victoria, boy babies born over the weekend were named “Air Force One” and “POTUS.”

All part of the long kwaheri, Swahili for “good-bye,” as Obama leaves Africa.

In Kenya, when he walked onstage at the Kasarani stadium to deliver his final speech, the crowd of 5,000 cheered the president as if he were a rock star. As the helicopter known as Marine One delivered the president to Jomo Kenyatta International Airport for his departure to Ethiopia, photos appeared on Facebook of grown Kenyan men in tears.

While in Nairobi, the President got and gave a lot of love—some of it of the tough variety delivered to his Kenyan counterpart, Uhuru Kenyatta. Obama pressed the Kenyan leader on such sensitive issues as gay rights, which Kenyatta called a “non-issue,” and corruption, about which he made no comment.

The top item on their agenda was Kenya’s fight against Al Shabaab, the Somali-bred Islamist group that has, in recent years, come of age with attacks inside Kenya. After warming up with the kidnapping and murder of tourists, al-Shabaab advanced to devastating acts of violence at malls and universities. Since Kenya invaded Somalia, in 2011, the Somali faction’s retaliation against soft targets on Kenyan soil has left more than 600 dead. And that figure doesn’t include those hundreds who perished when al Qaeda bombed the U.S. Embassy in 1998.

Saturday, in a joint press conference held at the statehouse here, Obama announced that the United States is providing Kenyan security forces additional funding and assistance to deal with terrorism and to make sure that the efforts made to root out terrorist threats do not create more problems than they solve.

The question left unspoken, however, is one that’s been weighing heavily on the minds of analysts, policy makers, and rights groups: What to do with Somali refugees at the Dadaab camp in Kenya’s northeast province, near the Somali border, which allegedly is used as a prime staging ground for al-Shabaab’s attacks.

Kenya’s refugee problems are not new, dating from the ’90s when Somalis fleeing the brutal dictatorship of Muhammad Siad-Barre put down roots in an area of Nairobi now called Eastleigh. It is home to over 50,000 refugees and asylum seekers, yet over time has become an important East African trade hub for the Somali diaspora in Nairobi.

Dadaab, now in operation 23 years, has grown from a tented village to become a small city that houses over 300,000 stateless people. According to Human Rights Watch, Kenyan security forces deployed to Dadaab since the 2011 invasion of Somalia have committed abuses and human-rights violations against refugees.

Shortly after April’s al-Shabaab assault on Garissa University, which left at least 147 dead, Médecins Sans Frontières took the precautionary measure of evacuating 42 members of its staff from Dadaab. The withdrawal had an immediate impact on MSF’s ability to provide medical care to the camp’s mainly Somali residents.

Kenya has since demanded that the UN move the camp’s population back to Somalia, and given a three-month deadline to do it. Human-rights groups pointed out that the move is, under the 1951 United Nations Refugee Convention, illegal.

Kenya’s Christians and Muslims have historically coexisted peacefully. Since counter-terror efforts were ramped up under George W. Bush’s Global War on Terror, Muslim communities along the country’s Swahili coast see themselves as having been marginalized and made victims of state-sponsored terror.

In May, U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry visited Kenya and mediated talks between President Kenyatta and the UN on the issue of Dadaab. Afterwards, Kerry said that the refugee camp would remain open, pledging $45 million to the UN High Commission for Refugees and continued efforts for voluntary repatriation.

Obama’s final speech at Kasarani stadium amounted to his welcoming acceptance of the country’s embrace, as a son of Kenya. It was probably not lost on the American president, however, that last year police had rounded up thousands of Muslims—mainly women and children—and detained them for three weeks on a soccer pitch a few hundred meters from the stadium where Obama was speaking. The mass detention came in reaction to a series of explosions in Eastleigh that killed six and injured more than 20 people.

Rights groups reported that police extorted money from men in Eastleigh and sexually harassed female detainees. Kenyan Interior Cabinet Secretary Joseph Ole Lenku said in a press conference in Nairobi at the time that all undocumented Somali refugees in Eastleigh would be deported back to Somalia.

Over the weekend of Obama’s visit, the two countries’ leaders spoke of “deepening of ties” on the matter of counter-terror.

Kenyatta declared that the war on terror is an “existential fight” of a kind Kenya has not previously experienced. The Kenyan president’s point was that Nairobi must have partners like Washington.

In the absence of an efficient judicial system, a major question in Kenya remains whether security forces will continue to use the hard-line, abusive approach in dealing with terror threats. Since 9/11, the U.S. has applied at least $200 million in aid money, disbursed through various agencies, to East Africa’s counter-terror efforts. During his visit in May, Secretary Kerry committed an additional $100 million to Kenya, an increase from $38 million the previous year.

Over the weekend Obama and Kenyatta came up with a plan that will further increase financial aid for the military, police, and judiciary under the Peacekeeping Operations program through the Partnership for Regional East Africa Counterterrorism. It’s still unclear the amount of funding that Obama has promised to Kenya and what strategies will be promoted.

Following the big roundup that led to lengthy detention at Kasarani, The Daily Beast established contact in Eastleigh with Lul Isack, chair of Umma, a community organization that had created a safe house for dozens of female detainees who reported being sexually assaulted and abused by police. In Somali societies women who’ve been raped are typically unable to find a husband, and married women are abandoned. Umma provided victims psychological counseling and surgical care.

Asked now whether she is worried about how the Kenyan government plans to use monies donated by the United States to Kenya for counter-terror operations, Lul said she was pleased that Obama had announced that the U.S. pledges $1 billion to support women and youth entrepreneurs worldwide and increase technical and financial support for young women entrepreneurs in sub-Saharan Africa. “I believe this is where we as a civil society organization come in, and we women now have a platform and our voices will be heard,” she says. “Kenya has challenges, but Obama is president of the most powerful country in the world and we believe the Kenya government will listen to him.”

Kenyan police continue to extort money from Somali businesspeople, says Lul, but the women she cared for managed to return to Somalia via voluntary repatriation—towns and cities like Mogadishu, Kismayo, and Hargeisa in Somaliland—and have succeeded in opening businesses, such as beauty salons.

After departing Kenya, Obama made his first trip ever to Ethiopia. There, he met with officials of the government, the African Union (AU) and the Inter-Governmental Authority on Development (IGAD), to discuss trade, the political crisis in South Sudan and the ongoing battle against Al-Shabaab.

The new mantra in Kenya, as elsewhere, is “trade, not aid.” Obama’s visit to East Africa is said to demonstrate the U.S. government’s firm commitment to the battle against terrorism in the region, and to help Ethiopia develop from an aid-recipient nation to a partner in a mutually beneficial trade relationship.

The president drew fiery criticism over the astronomical costs of his traveling to a conflict zone, but throughout his African journey he has appeared to be his usual cool, unflappable self, and already he is talking about returning to Kenya as a private citizen, when he can have more freedom to connect with his extended family and have hands-on engagement with poor communities.

“I can guarantee you I will be back,” the president said. “And the next time I am back, I may not be wearing a suit.” He won’t be on Air Force One, either.