AQUILA, Mexico — The vigilante attack squad is nervous now, waiting for the show to start.

Sitting in their trucks or slouched beside the vehicles in the midday heat, some of the men vent their adrenaline by restlessly clacking the safety switches back and forth on their assault rifles. Others chamber rounds and jack them back out again. They tap their wedding rings against their gun barrels, whisper bad jokes and friendly insults to each other in Spanish:

“Oye, Gordo, what do you need a bulletproof vest for with a gut like that?”

“I would rather be fat than ugly. Your smile alone could kill 20 narcos.”

“I’m going to use your gut for cover when the shooting starts, Gordo—because I know that belly would stop a bullet.”

It’s another hot and windless day in late August, in the southwestern state of Michoacan—one of the deadliest regions in all of Mexico—and more than 30 of the Aquila-based vigilantes are gathered in a clearing in the dry, upland forest of the Sierra Madre del Sur.

I’d been working at the computer in my air-conditioned, WiFi-equipped, and sissified hotel room when a vigilante patrol arrived to pick me up for this surprise operation. Now I’m in their world. After a kidney-bruising drive through the sweltering woods in the back of a pickup with the rest of the squad, we’re waiting for the chief’s order to assault the nearby ranch called Los Guaracheros—a base for the notorious cartel known as the Knights Templar (Caballeros Templarios).

A previous raid by this same group back in December had driven the cartel from the property. But the vigilantes’ power has waned of late, allowing a resurgence of criminal activity across Michoacan. According to a Guaracheros worker turned militia informant, the ranch is again home to an underground drug lab owned by the Templarios.

The men gathered in the clearing are heavily, but haphazardly, armed. Most carry AR15s or AK47s, but there are several pump-action shotguns, a few Uzis, even a handful of old M1 carbines that date to World War II.

Their clothes and equipment are just as motley. Some wear jeans and sneakers with their Kevlar vests, or pixelated camouflage sent down by relatives in the States. Others are dressed in the dark-blue uniforms of the Fuerzas Rurales (Rural Forces), a recently formed police unit with controversial ties to the government.

In fact, in the ranks of the Aquila vigilantes, the Rurales uniform is seen as just another poor joke.

“The shirt means nothing,” one man tells me, plucking at his navy polo, a Mexican flag emblazoned on the left sleeve. “This is just a disguise,” the vigilante says. “At heart we’re still autodefensas [self-defense groups].”

Up until about six months ago, large-scale anti-cartel operations by Michoacan’s storied autodefensas were as frequent as they were effective. Now they’re all but unheard of.

Starting in the early weeks of 2013, vigilante units made up of poor farmers enjoyed profound success driving out organized crime groups like the Knights Templar. But over the last two years factional infighting, cartel assassinations, criminal infiltration, and a harsh government crackdown have taken a great toll on the movement.

The Aquila squad is now one of the few still-active vigilante groups left in Mexico. As such, the men wear many hats in this rural municipality. In addition to being a potent, mafia-battling militia, they also serve as emergency first responders, ad hoc firemen, rescue workers, and the local highway patrol.

This afternoon’s raid on the Guaracheros ranch is supposed to be a joint effort involving a Federal Police task force. But the feds haven’t shown up yet. Finally the Aquila squad’s leader, Hector Zepeda, decides they can’t wait any longer without risking the element of surprise.

Zepeda whispers an order into his radio and the fighters spread out into three separate fire teams of about 10 men each. They start toward the ranch on foot, keeping plenty of space between them. All the pent-up anxiety is gone now and everyone looks glad to be on the move. Their rifles in ready position, they scale the foothills with farmboy ease, following Commander Zepeda up a narrow trail lined with spindly cedar and acacia.

“Watch for halcones [scouts] up on the hilltops,” Zepeda hisses into his radio. He stops to scan the peaks above the trail through a break in the trees. “This is a damned good place for an ambush,” he says.

And he ought to know. A few months ago, near the end of May, hit men from the Knights Templar tried to assassinate one of Zepeda’s co-commanders, opening fire on his truck as it passed through a wooded area near Aquila. Zepeda led the counterattack, which turned into a daylong running gun battle. The final standoff left four cartel gunmen and two of Zepeda’s vigilantes dead, along with several more wounded. But now the commander has learned his lesson: “Always clear the high ground first,” he says.

Once his men have secured the hills above the trail, Zepeda starts to climb again. But it’s clear he’s still worried that we might be walking into a trap. “It’s always like this with the government,” the vigilante leader says, lamenting the lack of reinforcements the federal police were expected to provide. “We take all the risk—and they take all the credit.”

When he comes to a barbed-wire cow fence that marks the edge of the ranch property, Zepeda orders radio silence. He flips a pair of wire-cutters from a chest pocket in his Kevlar vest and begins to clip through the strands. When the hole in the fence is big enough to crawl through, I expect Zepeda to order one of his men ahead of us, to take up the vulnerable point position. But instead, the vigilante leader slings his rifle and drops to his belly, sending a clear message to the squad: He’ll take point himself.

He’ll be the first man through the wire.

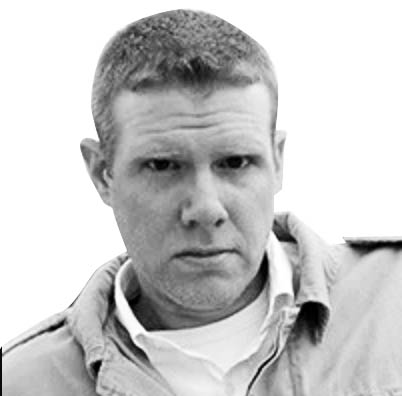

Zepeda, at 44, is lean and fit. He stands almost 6 feet tall, with jet-black hair and fine lines at the corners of alert, brown eyes. He’s soft-spoken yet dignified. But it’s the eyes that get you. His gaze is hawk-like, commanding, proud without being arrogant. The son of a grocery store owner in Aquila, Zepeda is not only one of the last of the vigilante chiefs still conducting operations—he was also one of the first.

In January of 2013, when his younger brother Julio was shot to death for failing to make extortion payments on his automotive repair shop to the Knights Templar, Zepeda and a close circle of friends armed themselves and went seeking justice.

“We lived like slaves under the rule of the Knights Templar,” Zepeda told me during our first meeting in his headquarters, a few days before the raid on the ranch. “Nobody would help us. So we had to defend ourselves.”

But defending themselves is harder than it used to be. Michoacan Governor Salvador Jara (who did not respond to interview requests for this article) has declared all-out war on the vigilante movement—forcibly disarming some groups, jailing leaders, and vowing to crush all resistance.

“The root of the problem is corruption, Zepeda said. “[State officials] have it in for the autodefensas for driving out the cartels—because they know they won’t get any bribe money from us.”

Due to the lethal shootout with the Templarios last May, Zepeda himself is now wanted by regional authorities. A federal judge has already overturned the evidence lodged against Zepeda and his Aquila-based co-commanders—and the vigilantes still conduct ops with the interstate police—but Governor Jara refuses to drop the charges.

Out at the Guaracheros ranch, once they’re through the barbed wire, Zepeda’s squad double times it up a steep brushy slope, using clumps of scrub juniper and ocotillo for cover.

As the forest gives way to rolling chaparral, the vigilantes employ basic but effective small-unit tactics to minimize exposure over open ground. The men take their cues from Zepeda, and all communication is done by hand signals in order to maintain radio silence.

But after several sweeps of the area, it appears the autodefensas have arrived too late. They’ve found what looks to be the ruins of a lab for processing crystal meth, including three deep holes in the earth where the cooking vats once sat. A smell of ammonia still rises from the pits, pipes and tubing snake through the brush—but the drugs and equipment used to make them seem to have vanished.

“They think we won’t know they were here,” Zepeda says, squinting to study the hill country spread out below us. “But we do know. There’s no way they could’ve moved everything out over the roads without our patrols seeing it.”

Then the vigilante chief notices a long line of upturned soil that runs like a scar across the flank of a nearby hillside—signs of fresh digging. He sends several of his men back to the trucks for shovels. When they return, it takes only a few minutes to hit paydirt, in the form of several barrels of anhydrous ammonia, used as a fixer in most meth labs. Once uncovered it gives off a reek like burning plastic.

The vigilantes next find a sealed vat of mercury, which smokes bluely when they crack it open. When the men turn up the first bag of methamphetamine hydrochloride, Zepeda cups a handful of the crystalline shards in his palm and thrusts it under my nose.

“This was just a temporary hiding place,” he explains. “They sealed everything up so they could come back for it later. The Templarios aren’t stupid,” he says. “They’re just waiting for the state to finish us off. Then, once again, they’ll be able to do as they like.”

The day after the initial raid, the autodefensas return with a backhoe to finish digging up the lab. As the massive, yellow excavator lifts yet another barrel from the growing trench in the hillside, someone taps me on the shoulder.

“Look there,” one of the vigilantes says, and points to the top of a broken rim rock on the other side of the valley that enfolds the ranch. “The Templarios are watching us.”

Through the telephoto lens of my camera I can just make out a tin-roofed cabin perched at the edge of a cliff, about a kilometer off to the west. The ridgeline there commands a view of the whole valley—an ideal observation point—and I can see several shadowy figures moving back and forth along the ledge, carrying what look to be automatic weapons.

“They don’t have the numbers to make a fight of it,” the vigilante tells me. “That’s why they’re staying up there out of range.”

And then, about 15 minutes later, half-a-dozen well-dressed women come roaring up out of the chaparral. They scream and wail and threaten the autodefensas, alternately pleading and raging, demanding that the digging be stopped. According to the vigilantes, these women are emissaries sent by the armed men up on the rim rock.

“Now you see what cowards these Templarios are,” Zepeda says to me. “They don’t have the guts to come down here themselves—so they send their women to fight for them.”

I approach the angry women with my hands up, waggling my tape recorder, hoping we really are out of range of their menfolk’s guns.

“What we do on our own property is our own business,” says Yolanda Lopez, 32, who claims the ranch belongs to her family. “These men aren’t real cops. They don’t have any authority. Who are they to go digging up our land?” says Lopez, who wears high-heeled espadrilles, a cropped shirt that shows off her midriff, and doesn’t look much like a rancher.

I’d like to ask Yolanda Lopez a few more questions, but now another stylishly-dressed Templario woman comes running over. “Go back to your own damned country,” she snarls, after viewing my credentials. She makes a sudden, violent grab for my camera, and that concludes the interview.

When the autodefensas refuse to shut down the backhoe, this same, camera-grabbing woman takes up a shovel and begins to swing it like a baseball bat. As the vigilantes duck out of her way, she screams threats of retribution, promises of cartel vengeance.

“Hector, you know who we are,” the woman says, shaking the shovel in Zepeda’s face. “And we know who you are. We know where you live. Where your wife lives. Your children. Do you really want to keep this up?”

“I’m sorry,” Zepeda says. “But it’s my job.”

“We have to make a living, Hector.”

“Yes,” says Zepeda, “but not like this,” and he nods over to the excavator, which is now pulling a bathtub-sized steel cauldron out of the ground.

Eventually, still spouting revenge oaths and death threats, Yolanda Lopez and the others start to back away from the still-smoking, meth-lab cache. As the women are leaving, a couple of his men ask Zepeda if he wants to have them followed, but he just shakes his head tiredly.

“We’ll let the Federales handle it,” he sighs. “Let them do something for a change.”

Later that same day, after the Templarios women have been gone for about an hour, several trucks full of federal troopers finally show up. According to police records, the vigilantes’ bust nets 200 liters of chemical precursors, 40 liters of pure acid, four 500-liter cooking vats, and several kilos of finished meth. They also tally gas masks, stoves, fuel tubes, and other production staples. And a marijuana packing station will be found, higher up in the hills, complete with a towering compression machine.

Despite the state warrant out for his arrest, Zepeda is greeted warmly by the federal officers.

“The autodefensas are our very good crime-fighting companions,” Inspector Carlos Carrion tells me. “We like to run operations with [the vigilantes], because they get better results. They know the terrain, and can go places we can’t,” says Carrion, 57, who is also the Federal Director for Public Security in Michoacán. “The secret to keeping peace is for the government to work closely with the autodefensas,” he says.

But when I ask Inspector Carrion if his report on the success of Zepeda’s latest raid could have any bearing on the warrant out for his arrest, or cause the regional D.A.’s office to go easy on him, the inspector adds a cryptic, ominous-sounding afterthought:

“In cases like this,” he says, “no one escapes the eyes of the state.”

After Zepeda turns control of the crime scene over to the feds, and we’ve started walking back to the trucks, I ask what he thinks the future holds for the autodefensas.

“Our biggest enemy used to be the Templarios,” he says, picking his way among the thorn bushes. “When they killed my brother, I didn’t think things could get any worse. But I was wrong,” says the vigilante commander, who is wanted now by both the cartels and the state.

“Como fuistes incorecto, señor?” says one of his men, with a note of genuine disbelief in his voice. What is it you were wrong about, sir? As if the idea of his revered leader being in error had never before crossed his mind.

“Now the enemy is our own government,” says Zepeda, and his hawk’s eyes are clouded by doubt for the first time since I’ve met him.

“And that’s a fight I don’t think we can win,” he says.