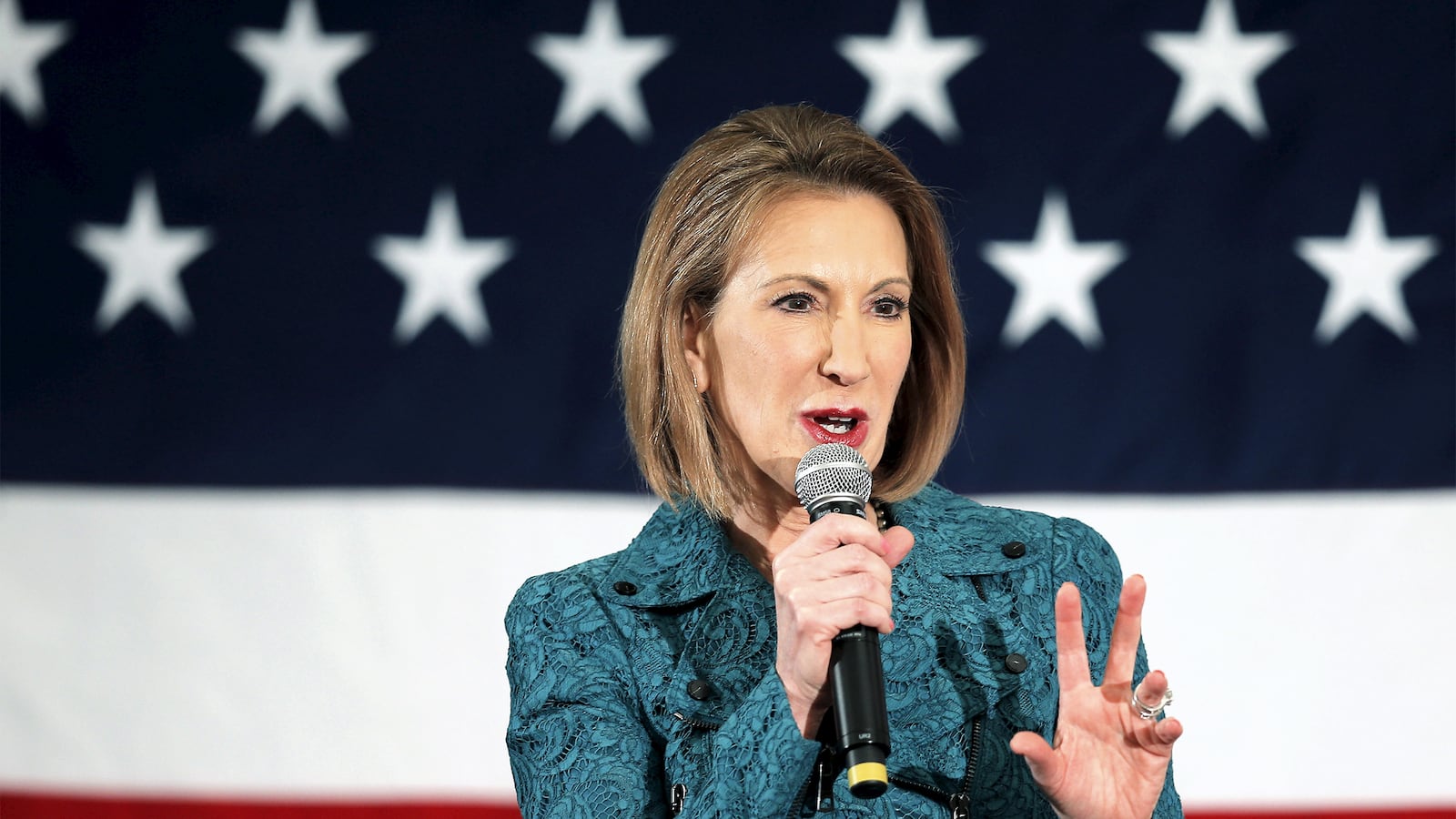

Carly Fiorina has a Mitt Romney problem.

Fiorina, like Romney, is a wealthy former CEO from an affluent Republican family. Like Romney, she entered the Republican presidential contest assuming that her record running a large company would be one of her greatest assets. But she may be about to learn that her opponents have little trouble turning that record into her greatest liability.

Like Romney’s tenure at Bain Capital, the private equity firm at which he oversaw the dismantling of numerous companies purchased by Bain, Fiorina’s record at Hewlett-Packard was notable for the number of workers fired on her watch. Romney’s Republican primary opponents, as well as the Obama campaign, attacked Romney’s record at Bain so aggressively that by the end of the 2012 campaign some people were using Bain as a verb: to destroy a wealthy candidate’s public image by attacking their business record.

Fiorina is about to get Bained. And if history is any guide, it’s an assault she may not be able to withstand.

“When you rise as fast as Fiorina has in the last couple weeks, all your opponents, plus the news media, are gonna pay attention to you,” Newt Gingrich, who ran for the Republican nomination in 2012 and acted as one of Romney’s most prolific critics, told me.

“The upside,” he said, “is now you’re more famous. But when you’re more famous, they come after you.”

Fiorina’s opponents have a lot to work with. Like most politicians, she likes to self-mythologize. Born in Texas in 1954, she says she is from “a modest, middle-class family.” She tends to leave out that her father, Joseph Tyree Sneed III, worked at the Justice Department, including as a deputy attorney general, before President Richard Nixon appointed him to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals in 1973.

Fiorina frequently tells of how she rose “from secretary to CEO” in a way that “is only possible in this nation” because it “proves that every one of us has potential.” In fact, she took the secretary job in between dropping out of law school and moving to Italy with her first husband, who last week emerged from obscurity to brand her as cold and calculating. She later went to business school, and after stints at AT&T and Lucent, in 1999 Fiorina became the CEO of Hewlett-Packard, the iconic technology company. She was the first woman in American history to lead a Fortune 100 company.

Her time running Hewlett-Packard was highly controversial. Fiorina deflects criticism of her 5½ years at the helm by noting that the company’s revenue doubled during that time. But, as Bloomberg View’s Justin Fox notes, “that was mainly because she made a gigantic and controversial acquisition.” Fiorina acquired Compaq, a computer manufacturer, for $19 billion in 2002—a move largely received by those within (PDF) and observing HP as unwise. Dell Computer’s Michael Dell called it the “dumbest deal of the decade.” By the time Fiorina was pushed out of HP three years after the Compaq deal, and given a $21 million severance package, HP had laid off 30,000 workers.

Four years later, in the midst of the Great Recession, Fiorina ran for a Senate seat from California. Barbara Boxer, her Democratic opponent, used the HP layoffs and Fiorina’s enormous severance to pillory the former CEO. During a September 2010 debate, Boxer asked if voters really “want to elect someone who made her name as a CEO at Hewlett-Packard, laying thousands and thousands of workers off, shipping their jobs overseas, making no sacrifice while she was doing it, taking $100 million. I don’t think we need those Wall Street values right now.”

Fiorina replied that “when you lead a business, whether it’s a nine-person business or 150,000 people, you sometimes have to make the agonizing choice to lose some jobs to save more.”

Later in the debate, a retired Hewlett-Packard employee named Tom Watson was allowed to ask Fiorina a question. “In a keynote speech in 2004, you said, ‘There’s no job that is America’s God-given right anymore.’ Do you still feel that way? What are your plans to create jobs in California?”

Fiorina didn’t answer directly. She said the loss of American jobs was the fault of the federal government for not incentivizing companies the way that China does with tax holidays and help cutting through regulations. In other words, those 30,000 people were laid off because of Washington, not because of Carly Fiorina.

It didn’t end there. The debate’s host noted that Fiorina had suggested teachers be paid in accordance with their performance. Why then, did Fiorina accept a $21,000,000 severance payment when she was fired from HP? Fiorina’s response wasn’t exactly steely. That was, she explained, what the HP board decided she should get paid.

Boxer needled Fiorina further. “My opponent—we know that she shipped jobs overseas, thousands of them,” she said, “we know that she fired workers, tens of thousands of them.”

Fiorina seemed at a loss for how to defend herself. “I think it’s absolutely a shame that Barbara Boxer would use Hewlett-Packard, a treasure of California, one of the great companies in the world, whose employees work very hard and whose shareholders have benefited greatly from both my time as CEO and all the hard work of the employees, that I had the privilege to lead, I think it’s a shame that she would use that company as a political football,” she said.

A few weeks after the debate, Boxer released an ad titled “Outsourcing,” which slammed Fiorina for the HP layoffs, for “tripling her salary,” buying “a million-dollar yacht” (she has two) for herself and “five corporate jets” for HP. Fiorina’s poll numbers immediately plummeted. In the Democratic wipeout year of 2010, Boxer managed to defeat Fiorina by 10 points.

Fiorina knows similar attacks are coming as she makes a run at the presidency. You could almost see the impending sense of doom on her face during Wednesday night’s Republican debate.

“Ms. Fiorina, you were CEO of Hewlett-Packard,” CNN host Jake Tapper said. “Donald Trump says you, quote, ‘ran HP into the ground,’ you laid off tens of thousands of people, you got viciously fired. For voters looking to somebody with private-sector experience to create American jobs, why should they pick you and not Donald Trump?”

Fiorina’s reply felt lived-in, like she had long ago decided on the proper delivery—almost Carlin-esque, fast-paced and melodic—for such a message. She looked as though she had practiced every syllable and plotted out every point at which she would pause to take a breath.

“I led Hewlett-Packard through a very difficult time,” she said, “the worst technology recession in 25 years.” Despite the circumstances, she said, she led the company to success. She rattled off her supposed accomplishments: “We doubled the size of the company, we quadrupled its top-line growth rate, we quadrupled its cash flow, we tripled its rate of innovation.”

Donald Trump looked on, smirking and rolling his eyes with meme-worthy animation.

“Yes, we had to make tough choices,” she said. But, she said, firing thousands of people actually “saved 80,000 jobs,” which led to the growth of “160,000 jobs.” And how dare Trump of all people make such a criticism, Fiorina said, since “you ran up mountains of debt, as well as losses, using other people’s money and you were forced to file for bankruptcy not once, not twice, four times. A record four times. Why should we trust you to manage the finances of this nation any differently than you managed the finances of your casinos?”

Fiorina’s defense of her time at HP was a minor blip in her debate performance, which saw her bash Trump for his recent attack on her looks and open up about losing her stepdaughter to drug addiction.

She received rave reviews from the media and vaulted up in the polls from 3 percent at the beginning of the month to 14 percent in a CNN/ORC poll released Sunday. Fiorina’s rise coincides with the first signs of Trump’s decline. Though still in the lead, Trump fell from 32 percent to 24 percent in the CNN poll.

Fiorina is, understandably, feeling optimistic. Asked if she would like to speak with me for this story, Fiorina’s deputy campaign manager, Sarah Isgur Flores, emailed, “I’m swamped today. But I’m sure it’ll be good without me :)”

As the emerging candidate of the moment, Fiorina should expect the coming Bain-like attacks on her record will intensify perhaps beyond even what she experienced in 2010. In The Gamble, a data-driven analysis of the 2012 election, political scientists John Sides and Lynn Vavreck argue that although “the polls seemed almost random” in the Republican primary, “there was an underlying logic at work.” That logic, according to Sides and Vavreck, can be described as “discovery, scrutiny, and decline.”

When a candidate does something to capture the public’s attention—getting into the race at all, in the case for Trump, or delivering a breakout debate performance, for Fiorina—the “discovery” of the candidate results in an increase in media attention, which in turn results in a surge in the polls. But with increased attention comes increased scrutiny from both the media and primary opponents and the barrage of negative information reliably results in an “irreversible decline in both news coverage and poll numbers.”

Sides told me that “Fiorina is a textbook case of discovery. For months, her candidacy received limited media attention. Then, thanks to Trump’s comments and last week’s debate, she received much more coverage, and her poll numbers responded accordingly.”

Rick Perry, Herman Cain, Michele Bachmann, and Newt Gingrich all experienced these cycles in 2012. Only Romney survived. Sides and Vavreck write that Romney had the advantage of a well-run organization and fundraising operation, more support from Republican leaders than other candidates, and the good fortune of being “the most popular candidate among the largest factions in the party, which tend not to be the most conservative factions.”

But the anti-Bain attacks, launched by Gingrich and others during the primary, left Romney vulnerable in the general election. There was an incessant drip-drip of negative information about Romney’s immense personal wealth and his time at Bain Capital released by his Republican rivals that enabled Democrats to latch onto the narrative of Mitt-the-jobs-destroyer so easily.

The most memorable of these assaults came from Winning Our Future, an “independent expenditure-only committee” supporting Gingrich’s campaign that distributed When Mitt Romney Came to Town, a 28-minute attack documentary that felt like a cross between an episode of American Greed and a Michael Moore documentary. The movie accused Romney of everything from “stripping American businesses of assets, selling everything to the highest bidder and often killing jobs for big financial rewards” to “contributing to the greatest American job loss since World War II.” Devastatingly, it featured interviews with real people (some of whom had no idea they were being interviewed for an attack ad against Romney) who described in painstaking detail the misery of losing their jobs as a result of Bain Capital’s actions.

“We thought that it was a legitimate question to raise and also that it was something that Barack Obama was going to raise, which of course he did,” Gingrich told The Daily Beast. “I think it’s the same thing as attacking me for my record as speaker,” he said. Which is to say, Gingrich thinks any candidate’s history is fair game.

“Anybody at this point is going to have a record in their career or they wouldn’t have gotten here. So, it’s fair to go after Trump for his business record. It’s fair to go after Carly for hers. It’s fair to go after Jeb for his governor’s record. If you’re gonna run for president you’d better expect that you’re gonna be thoroughly challenged—and you should be! We give presidents of the United States an enormous amount of power and whoever wins that office should be thoroughly tested.”

Asked how he would run against Fiorina were he in this Republican primary, Gingrich said, “I have no idea. I have been so confused by this primary season so far.”

When it came time for the general election, branding Romney as an out-of-touch, car-elevator-riding bully-of-the-working-class proved an easy task for Democrats. All the work had already been done for them by Gingrich & Co.

Will Fiorina ever make it that far? It’s at best a longshot.

She has all of the downside of being a wealthy and controversial former CEO like Romney, but none of the benefit—the establishment support, the fundraising operation, the organization, or the four years as governor of Massachusetts—that insulated him against the “discovery, scrutiny and decline” pinball machine and helped him win the primary.

“She’s smart, Fiorina knows this is coming and she knows exactly what it’s gonna be like, because she’s already lived through it once,” Gingrich said. “My guess is that she must believe that she has a stronger, more convincing answer than she had in the Senate race in 2010.”

It’s true that Fiorina may now be a better prepared and more polished candidate than she was when she last ran for office, but the substance of her answers to questions about HP hasn’t changed much at all.

But to hear Gingrich tell it, when you’re the longshot who is suddenly surging, that doesn’t really matter. “I’m sure it’s more fun to be one of the top two or three candidates and have to defend yourself than to be in the bottom tier and and have nobody paying any attention to you,” he told me.

And isn’t that what a presidential campaign is really about?