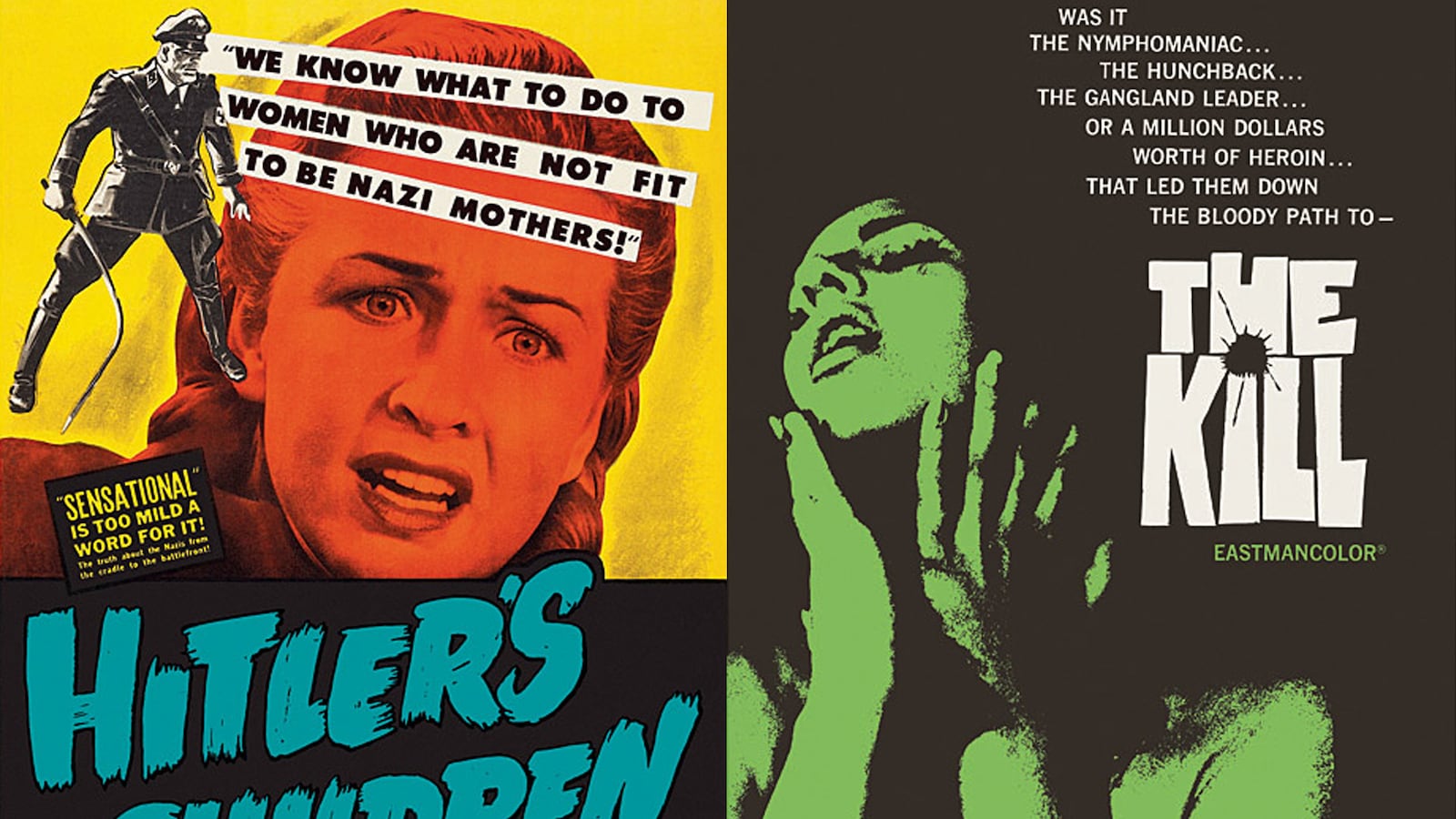

Spiked Heels and Black Nylons. The Twisted Sex. Torture Me Kiss Me.

There’s nothing quite like the lurid pull of a movie poster that screams out to your basest desires, as Drive and Only God Forgives director Nicolas Winding Refn proves with Nicolas Winding Refn: The Act of Seeing, a new cult-art book showcasing stunningly salacious exploitation cinema one-sheets from the 1960s and ‘70s.

“They had to be shameless because they were basically just catering to sin,” Refn offered via phone from his home in Copenhagen, days before flying to Austin’s Fantastic Fest to unveil the book. “Presenting these posters for films that were considered trash when they came out, if you present them again in a higher way, it almost becomes like the Warhol trick. Suddenly there’s art in soup cans. There’s art in trashy movies.”

Culled from Refn’s personal collection of over a thousand meticulously preserved vintage posters and curated by the director himself, The Act of Seeing is tailor-made for cult cineastes. Refn describes it as a time travel machine to the heyday of the kind of tawdry B-movies he was never allowed to indulge in as a kid, when his family moved to New York City in 1978.

“A lot of these films were made during repressed times,” he said. “So the posters work on the assumption that you might see a naked breast or whatever desire you wanted to see… but there seems to be a lot of whipping and a lot of naked women through the entire book.”

Back then, the eight-year-old future auteur wasn’t allowed to patronize the trash cinema wonderlands that dotted NYC’s Times Square, the 42nd Street grindhouses that inspired the Tarantino generation.

“It was like getting in a TARDIS from Doctor Who and being brought back to an era that, in a way, I romanticized,” he said. “To experience the heyday of not so much exploitation, but the idea that there were cinemas next to cinemas all promising to fulfill every desire you ever wanted to see. It was almost like I wanted to try to relive something I will never be a part of, because I was too young.”

Presented in vivid color, the posters hand-picked and curated by Refn (and contextualized in glorious detail by film scholar Alan Jones) run the gamut from every kind of exploitation cinema known to man: Blaxploitation, nunsploitation, Nazisploitation, nudies, mondo, you name it.

Some, like 1971’s infamous Italian faux-documentary Farewell Uncle Tom, about an Italian film crew going back in time to the Antebellum South to film the brutalities of slavery. That film inspired Refn so much he referenced it in Drive, using Riz Ortolani’s beautiful theme song “Oh My Love” as the soundtrack to Ryan Gosling’s brutal descent into violence.

“I always liked the mondo movies from the ‘60s a lot, especially the soundtracks and the ones by Jacopetti and Prosperi, who made the first Mondo Cane,” said Refn, who will present a rare screening of Farewell Uncle Tom this week at Fantastic Fest—with fair warning to the audience.

“It’s an extremely sleazy movie by the nature of how in your face it is. It’s an incredible mix of fake documentary and fictionalized storytelling—all in, I guess, bad taste,” laughed Refn, who is currently in post-production for his next film Neon Demon, the female-led horror thriller he shot earlier this year in Los Angeles.

“At the same time, it’s very hypnotic and it’s quite an extraordinary film. I don’t know if it’s good… but it’s extraordinary. And it’s very extreme, so extreme that you could probably never make a film like that anymore, and that’s also what I like about it.”