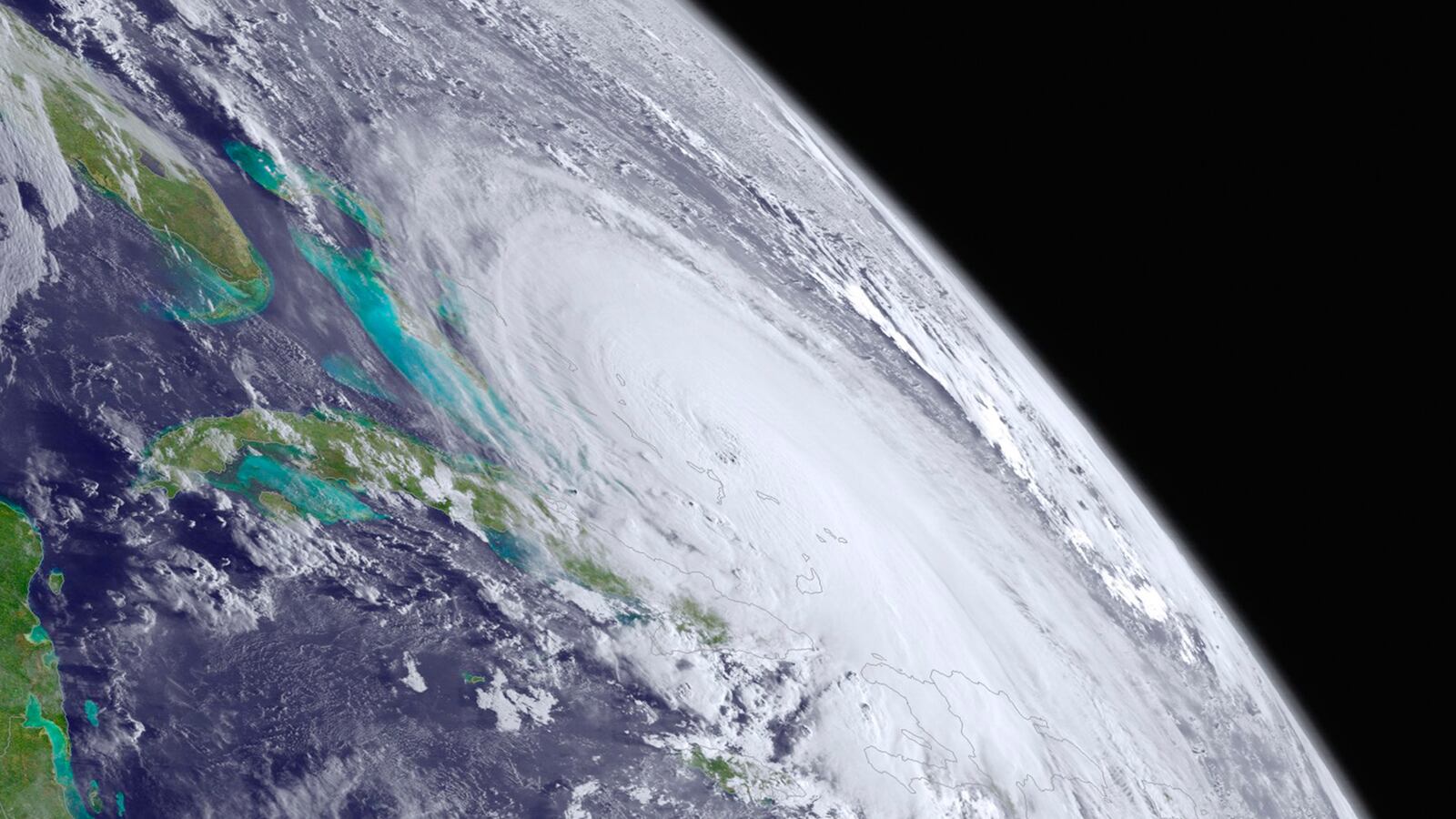

As of Friday morning, Hurricane Joaquin has slowed to a 3 mph crawl as it slams the Bahamas. The likelihood of Joaquin turning next to the U.S. coast diminished since Thursday as computer models converge on the storm heading out to sea. But regardless of the hurricane’s trajectory, the weekend will bring significant weather impacts up and down the Eastern coast of the U.S.

Forecasters cite two main sources of weather woes: heavy rainfall and a rare, prolonged wind event. The rainfall is from an area of low pressure—unrelated to Joaquin—churning its way across the deep South, pulling in tropical moisture as the weekend progresses. Forecasters predict the heaviest rains (5-8 inches) will fall in South Carolina, which has already experienced deadly flooding this week. Additional rainfall on top of already-saturated soils will likely lead to flooding conditions even more dangerous than that already seen this week.

While the wind is not expected to cause significant damage directly, it is expected to cause flooding in coastal areas. The wind is related to Joaquin—it’s the product of the pressure gradient between a strong high pressure system in eastern Canada and the low pressure system of Joaquin.

As Hal Needham, a storm surge scientist from Louisiana State University, wrote on Thursday, the wide-scale winds from this event will steadily push water toward the coast. Coastal flood and wind advisories have been issued from Florida to Maine, with some of the strongest warnings for the New Jersey coast, where there is potential for over 100 hours of 20+ mph winds coming onshore.

Beach erosion is one of the major expected impacts and has already been reported in Cape May. In areas that see a combination of both very heavy rains and a strong storm surge from wind, flooding could be exacerbated by rainfall failing to drain into rivers, bays, and the ocean due to the surging sea waters.

El Niño, the climate phenomenon that originates in the Pacific Ocean, influences the ocean and atmosphere in the Atlantic basin as well. El Niño events, such as the one underway, typically mean higher wind shear and fewer hurricanes in the Atlantic. Hurricanes need to stack vertically to produce the engine-like system that sustains them, and high wind shear, which is the changing of wind direction with height, makes it harder for them to stack. But the higher wind shear associated with El Niño isn’t uniform across the entire ocean, and variations bring opportunities for hurricanes to form.

“When Joaquin was first organizing, it had to fight some wind shear, but it was able to overcome that,” said Dennis Feltgen, spokesperson for the National Hurricane Center. “Then the wind shear disappeared completely as it approached the Bahamas, and it entered extremely warm water there that fueled its strengthening.”

Major Atlantic hurricanes (Category 3 or stronger) have occurred during El Niño, but in the stronger El Niño events they are rarer. This is the second major hurricane in the Atlantic so far this season, which is as many as the number of major hurricanes in the top three El Niño events since 1950 combined.

Wind shear is likely to still play a role in the fate of Joaquin; it doesn’t only suppress storm formation, it can also tear apart storms that already exist.

“When you have high wind shear, the bottom part of the storm goes in one direction and the top goes in another, and it just falls apart,” said Feltgen. The latest forecast from the National Hurricane Center indicates that Joaquin should start to weaken on Saturday as wind shear increases. This is what happened with Hurricane Danny earlier this year, he said. The storm became a major hurricane, then ran into a huge area of wind shear and collapsed.

It only takes one, however, as Suzana Camargo, a research professor at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, pointed out. “Case in point is Hurricane Andrew,” said Camargo. “One of the most destructive hurricanes in U.S. history did happen at the end of the 1991-92 El Niño event. Bottom line is, people need to be prepared for hurricanes even in years of low activity.”