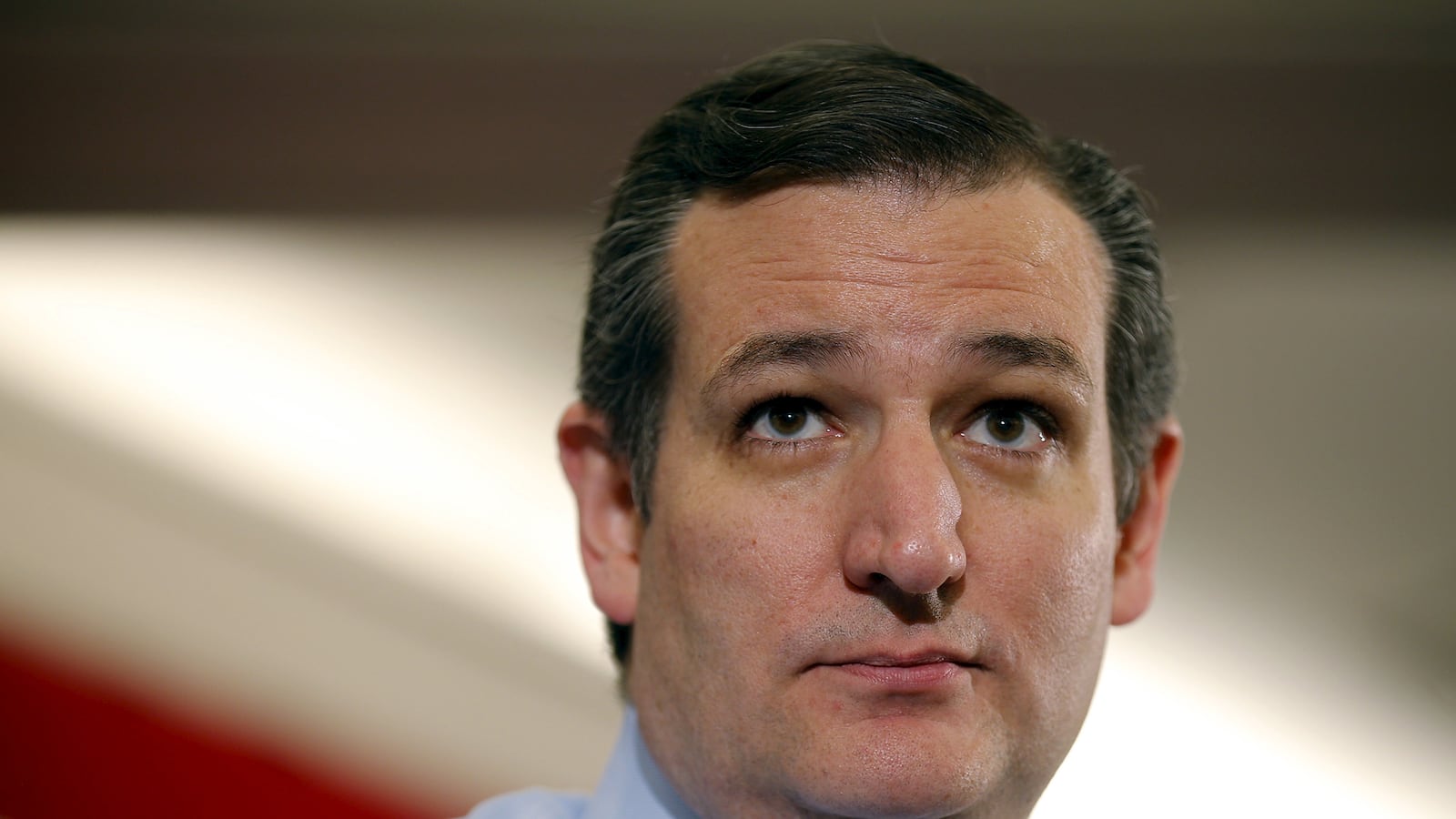

Presidential candidate Sen. Ted Cruz voted against a bipartisan effort to reduce mandatory minimums, citing a “growing crime wave” that criminologists are skeptical of and surprising criminal justice reform advocates who thought he stood with them on the issue.

To justify his stance, Cruz pointed to fear of a violent crime wave that’s sweeping the nation. But there’s a problem with the senator’s justification: Experts say it’s baseless.

The bill reduces mandatory minimums for non-violent drug offenses, which Cruz supports, but the Texas Republican broke with 15 other members of the Senate Judiciary Committee to join with four other senators because of provisions that loosened mandatory minimums for gun-possession offenses.

Cruz, who is polling third in Iowa, entered the presidential campaign with a strategy to position himself just to the right of Sen. Rand Paul, the GOP presidential candidate who has spoken at length about the need for serious criminal justice reform in America. But Paul’s libertarian-leaning philosophy has faltered on the campaign trail, creating an environment which gives Cruz more political flexibility on the issue of mandatory minimums.

The Texas Republican said that a spike in crime across the country should give lawmakers pause before loosening penalties for criminals.

“When police officers across this country are under assault right now, are being vilified right now, and when we’re seeing violent crime spiking in our cities across the country,” Cruz said, “I think it would be a serious mistake for the Senate to pass legislation providing for 7,082 convicted criminals potentially to be released early, a substantial portion of those criminals will be illegal aliens with criminal convictions.”

But criminologists say it is too soon to make the claim of a dangerous uptick in violent crime.

The best source of data on national crime trends comes from the FBI, which releases its Uniform Crime Report every year. In explaining his newfound opposition to mandatory minimum sentencing reform, Cruz cited “the growing crime wave.” Unfortunately, the FBI hasn’t released any data about nationwide crime this year, and data for 2013 and 2014 indicated anything but a sweeping trend toward increased criminal activity.

Richard Rosenfeld, a professor of criminology at the University of Missouri-St. Louis and former head of the American Society of Criminology, said Cruz’s crime-wave assertion doesn’t make sense.

“Ted Cruz’s presumption of a crime wave…that’s groundless,” he said. “It’s possible; we simply don’t know.”

Cruz’s offices pointed to a number of news reports that referred to growing crime in the country, and also pointed out that the FBI director has speculated that public criticism of law enforcement due to controversial incidents of police brutality may be related to a rise in violent crime.

A spokesman also clarified that Cruz was not referring literally to an uptick in assaults on police, but rather an increase in criticism.

“When Sen. Cruz spoke about the assault on police, he was referring to the additional criticism and scrutiny of police officers, not necessarily more physical assaults on police, though the recent killings of police officers who have been targeted for merely being police officers is nonetheless still extremely concerning,” a Cruz spokesman said.

While there has been an increase in homicides in some U.S. cities this year over last year, headlines have given a misleading and exaggerated picture, according to analysis at FiveThirtyEight. They looked at numbers for the 60 most populous U.S. cities and found that overall, homicides were up 16 percent over 2014. But the changing number of homicides varied widely from one city to the next; while homicide is up 81 percent in Tulsa and up 20 percent in Chicago, it’s gone down by 44 percent in Riverside, Calif., and 43 percent in Boston.

So while Cruz can intimate that a surge of violent crime sweeping the nation gives him a good reason to vote against a bill that lowers mandatory minimums for non-violent offenses, there isn’t broad empirical evidence to undergird his assertion.

This isn’t the first time the Texan has made faulty claims about crime in America. In September, he suggested that President Obama was responsible for an uptick in violent attacks on police officers.

“Cops across this country are feeling the assault,” Cruz said after a New Hampshire campaign stop, according to MSNBC. “They’re feeling the assault from the president, from the top on down as we see, whether it’s in Ferguson or Baltimore, the response of senior officials of the president, of the attorney general, is to vilify law enforcement. That is fundamentally wrong, and it is endangering the safety and security of us all.”

But as Radley Balko explained at The Washington Post, this year is on pace to have an exceptionally low number of cop killings. The rate of cops killed per 100,000 is also low and getting lower. And the rate of violent assaults on officers is going down, too. The conservative American Enterprise Institute think tank concluded that this year “will likely be one of the safest years in history for police.”

Criminal justice reform advocates who have worked with him were surprised by Cruz’s change of heart.

Explaining his opposition to the bill last week, Cruz said he would vote against it because “it extends beyond the terrain of nonviolent drug offenders to sweep in violent criminals, to sweep in criminals who have used a firearm in the commission of a crime,” and that making its new mandatory minimums retroactive could make thousands of prisoners eligible for release.

Cruz has historically supported reducing mandatory minimums for non-violent crimes, while still advocating for harsher sentences for violent crimes. This bill could have provided him some cover on this front, given that it created a new mandatory minimum for domestic violence crimes and for providing weapons to terrorists.

But advocates on the issue argue that the argument for loosening mandatory minimums applies regardless of what crime is concerned.

“I was a bit perplexed,” said Molly Gill, government affairs counsel for Families Against Mandatory Minimums. “Mandatory minimums [for violent crimes] are like all mandatory minimums: they can produce unjust results, punishments that don’t fit the crime, and can give prosecutors too much power in the sentencing process… They’re also extremely expensive, and because you’re applying them indiscriminately to a wide group of people, you are not necessarily getting more safety simply for locking people up for 5, 10, 20 years.”

“He didn’t seem to connect those same principles with the gun context,” she added.