With racial tension dominating conversations on college campuses and media coverage making it seem as though our country is on the brink of another civil war, it is understandable that some Americans may feel a sense of hopelessness. But it might come as a surprise to some to learn which Americans are less likely to feel this way. According to two recent reports, poor black Americans are the most optimistic Americans.

While these research studies were completed before the recent unrest at the University of Missouri and Yale, they were both completed after the racially charged death of Trayvon Martin. One was completed after the deaths of Michael Brown, Walter Scott, and Freddie Gray, and days after the tragedy in Charleston, South Carolina. The shooting deaths of black churchgoers there was arguably one of the darkest days in black America, and frankly all of America, since the height of the civil rights movement decades before.

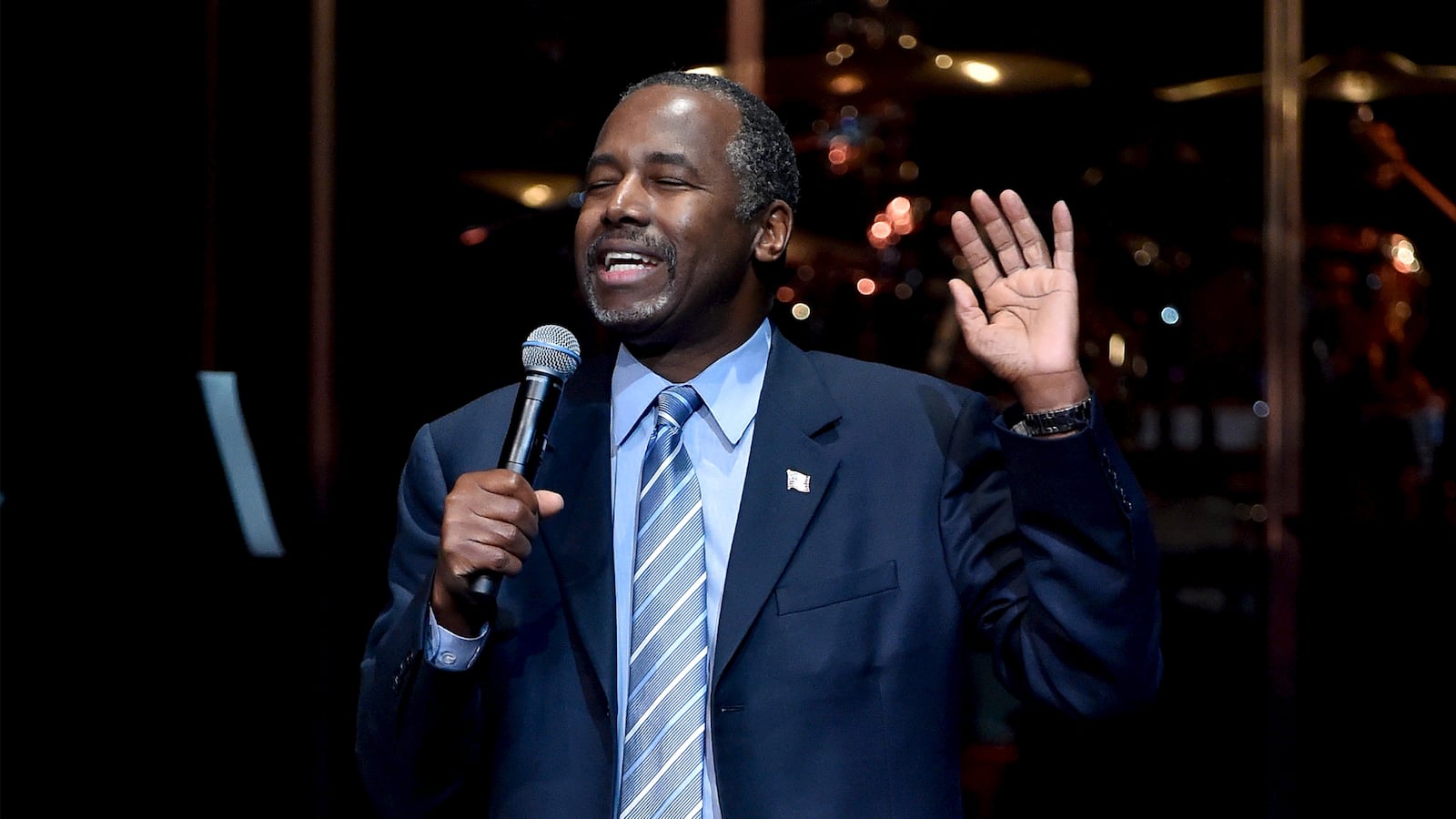

So what explains the optimism of black Americans, and what does it mean for the 2016 presidential election? Well, for starters it means that despite the disdain of media elites, and Donald Trump, Ben Carson’s star will continue to rise.

According to a recent analysis of the Gallup Healthways report recently completed by the Brookings Institution, historically happiness and optimism have been tied to some pretty reliable predictive factors. Despite the mantra “money can’t buy happiness,” traditionally the rich tend to be happier and wealthy, and more-educated people tend to be more positive. Anyone who reads the news knows that black Americans are not overrepresented among America’s wealthy. The net worth of African-American households is on average less than one-tenth of the worth of white households. And yet Brookings stumbled upon a surprising finding. According to Research Fellow Carol Graham, “black Americans are by far the most optimistic racial group. Most optimistic of all poor groups are blacks in poverty. Poor blacks are in fact more optimistic about the future than the sample as a whole.”

This gibes with recently published data by the Aspen Institute which found that black Americans are more optimistic and more likely than white Americans to say the American Dream is alive and within reach for those willing to work for it.

So why are black Americans—who by most significant measures, such as health, education, and finances, have reason to be pessimists—able to see America as a place in which the glass is half full instead of half empty?

For starters, when you’ve really known pain, you have an easier time appreciating when wounds begin to heal. Even if you’re not 100 percent healthy yet, you will have an easier time believing that getting well is possible. In other words, someone who’s battled a terminal illness and survived is going to be less likely to complain about a cold than someone who’s never so much as sneezed. For black Americans like my grandparents and parents who endured segregation, toiled on farms picking cotton, and cleaned houses for a living, the America of today remains imperfect, but it also represents proof that things can get better. Maybe not perfect, but certainly better. That’s what optimism is about.

But of course optimism is ultimately rooted in faith. Optimism in the American Dream is the belief that you can obtain the American Dream, even if no one you know personally has yet. Therefore it’s not a coincidence that optimism is more pronounced among black Americans since religious faith is more pronounced among black Americans. The Gallup data revealed that while fewer than 70 percent of white Americans identify religious faith as important to their lives, nearly 90 percent of black Americans do.

Studies have consistently found a connection between church attendance and happiness. Which brings me to the current presidential election.

The reason Ben Carson continues to surpass the expectations of the pundit class is that while they were busy ridiculing the religious-themed artwork that decorates his home and playing “gotcha” with his biography, he continued to play against type. Instead of becoming the combative angry black man who is one of America’s most enduring and inaccurate stereotypes, he has maintained a Mr. Rogers-like aura of calm. While The Donald stays on the attack, Carson says he’ll pray for him.

What media and Republican establishment figures don’t get about Carson is that part of the reason attacks on his biography haven’t landed is that Americans like redemption stories, and like people who instead of blaming the world for their circumstances, set out to change them—and succeed.

Unlike Trump, who was born into the American Dream—and yet is still angry—Carson was born into an American nightmare, but his optimism and faith got him where he is today, with a life that epitomizes the American Dream.

While they may have little in common in terms of policy, Carson’s less than ideal childhood, and the optimism necessary to overcome it, echoes another previous candidate. President Obama didn’t come from privilege like his presidential opponents Sen. John McCain and Gov. Mitt Romney. So he had to have faith in the American Dream to ascend to the halls of power predominated by sons (and daughters) of privilege.

Maybe the rise of Ben Carson is simply proof that despite Trump-mania Americans don’t want to be believe in the politics of pessimism. We want to believe in our country’s greatness and possibilities. We want to be optimistic.