In the mid 1970s when I moved to Manhattan the Upper East Side was still very much the art district. And Les Pleiades, a French restaurant on East 76th, notorious for the execrable paintings on its walls, was where the art world in which Leo Castelli and Ileana Sonnabend were totemic presences on daily display.

That was where European dealers would be likely to show their faces soon after they got in from JFK and for more casual cruising there was the Bemelmans Bar in the Carlyle or Three Guys, just across Madison, a diner that Warhol used often enough and liked well enough to put into his diary. It was an old school art world, deceptively genteel, steely fingers in soft gloves.

Then the earth moved. SoHo.

You will have noted that only dealers seem to have occupied that particular haute art continuum, not artists, the inevitable Andy aside.

With the rise of SoHo, though, a melt began, as the art world we know today was being born, and the most public birthing took place in hangouts.

Fanelli’s at 94 Prince was one of the first and deservedly so. Records show that a saloon had been on the spot in 1863. It became Fanelli’s in 1922 and its well-worn ambiance, which includes a wall of vintage boxing photos, commended it to the crowd who took over as the art boom took hold.

Other art-inflected eateries were budding, like One Fifth and Raoul’s.

Below SoHo in the raw, freshly named district, TriBeCa, were El Teddy’s, Magoo’s and Puffy’s Tavern on Harrison and Hudson.

Then in 1980 Keith and Brian McNally opened Odeon on West Broadway, along with Keith’s wife, Lynn Wagenknecht. I have written about the McNallys elsewhere, both shortly after the opening, and most recently in the Brit glossy, Tatler.

Odeon was also in TriBeCa. Max’s Kansas City had been the hub of the art world between the mid-’60s and the early ’70s when it was tiny, brilliant, intense, and Max’s could be feral.

Brawls were not unknown and some rambunctious artist could be thrown through a plate-glass window.

Not so at Odeon. The place was mellow. Just one year and some months after its opening it was the venue for a group photograph of Leo Castelli and 19 of his artists, including Robert Rauschenberg, Ed Ruscha, Richard Serra, Jasper Johns and, yes, Andy Warhol. And that was just the beginning.

The McNallys split up bitterly though. And what was then remarkable was that Keith and Brian would independently put together a sequence of joints, each wholly different in its conception and often in some unexplored part of Manhattan and each of which would infallibly become a hit.

It was Brian who started Indochine on Lafayette opposite the Public Theater, for instance. Yes, Downtown. The art world was there already, of course, but now the fashionistas and the party people were in stampede mode below 14th Street and Indochine would be where a gallerist’s dinner for an opening might be alongside a fashion week hoedown, some movie people would be in a banquette, and nobody saw any cause for surprise in what just a few years before would have been seen as a scenario of Worlds in Collision. Brian then went on to do 150 Wooster and 44 in the Royalton.

Florent was another gamechanger. It was opened in 1985 by Florent Morellet, the son of a French artist, on Gansevoort, a cobblestone street in the core of a then-utterly unfashionable chunk of Manhattan real estate, known to cognoscenti for its hardcore clubs and exotic sexlife.

Florent was a joint where Roy Lichtenstein, whose studio was nearby, had a regular table and where artworlders and fashion folk would eat and drink as raw sides of beef were trundled past the front window by aproned folk from the trade that gave the area its—now only metaphorically appropriate—name: The Meatpacking District.

It was Keith McNally who put up the dough that enabled Nell Campbell, an Australian fresh from London, to open Nell’s at 246 West 14th Street.

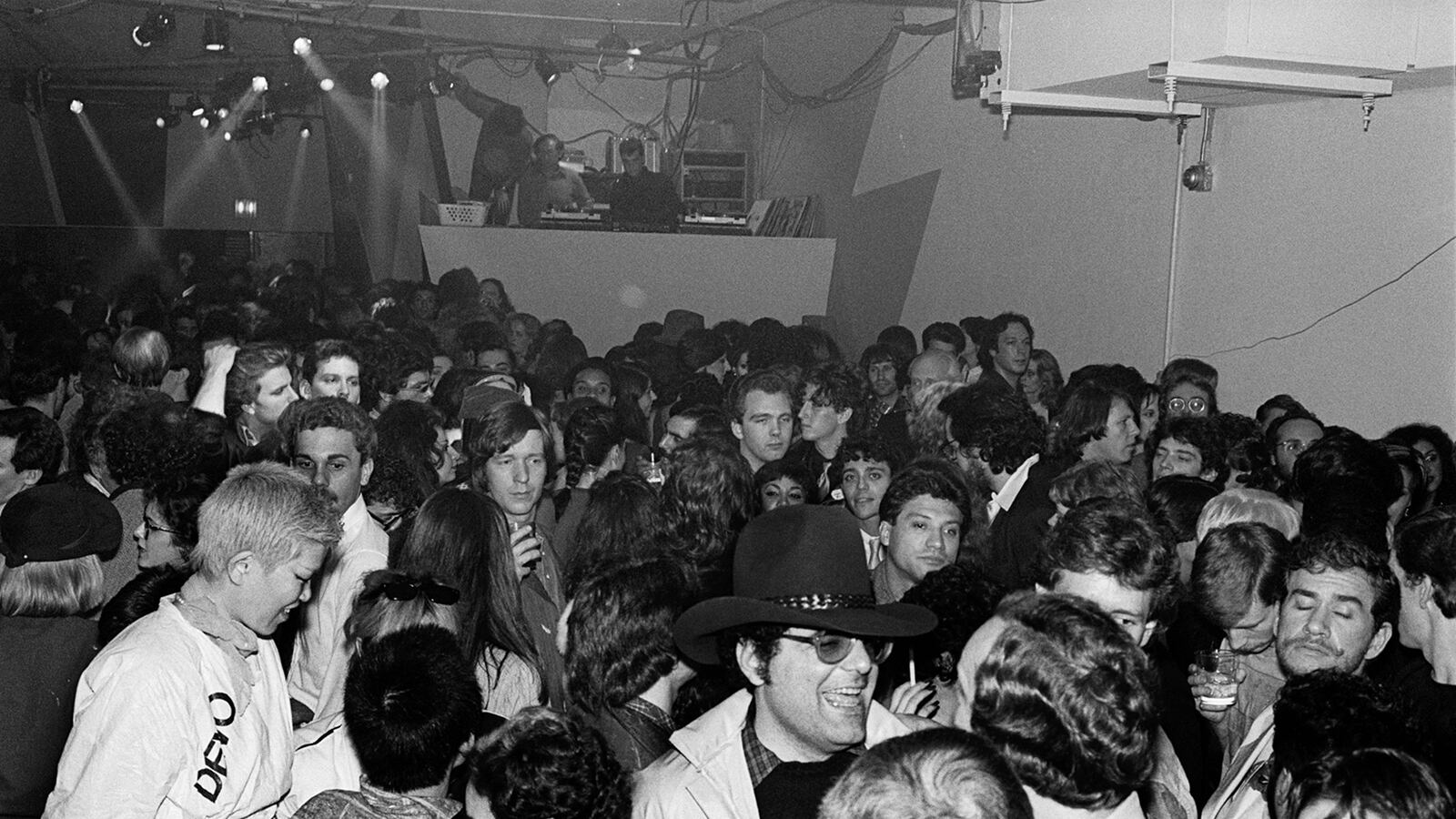

Nell’s opened in the fall of 1986. It was ripely furnished in the manner—or so I imagine—of a High Victorian brothel so it inevitably became The Place, and was duly referenced as such in Andy Warhol’s Diaries.

Well, Warhol was dead the following year, and certain other of the names you have spotted here have followed.

And New York’s nightworld? Despite sporadic obituaries, wails of loss, cries of finis and curtain calls, it continues. Max Fish opened at the top of Ludlow at the end of the ’80s. It closed, moved, and has reopened. New York changes, but continues. It is, after all, the world capital of not only change, but also reinvention.