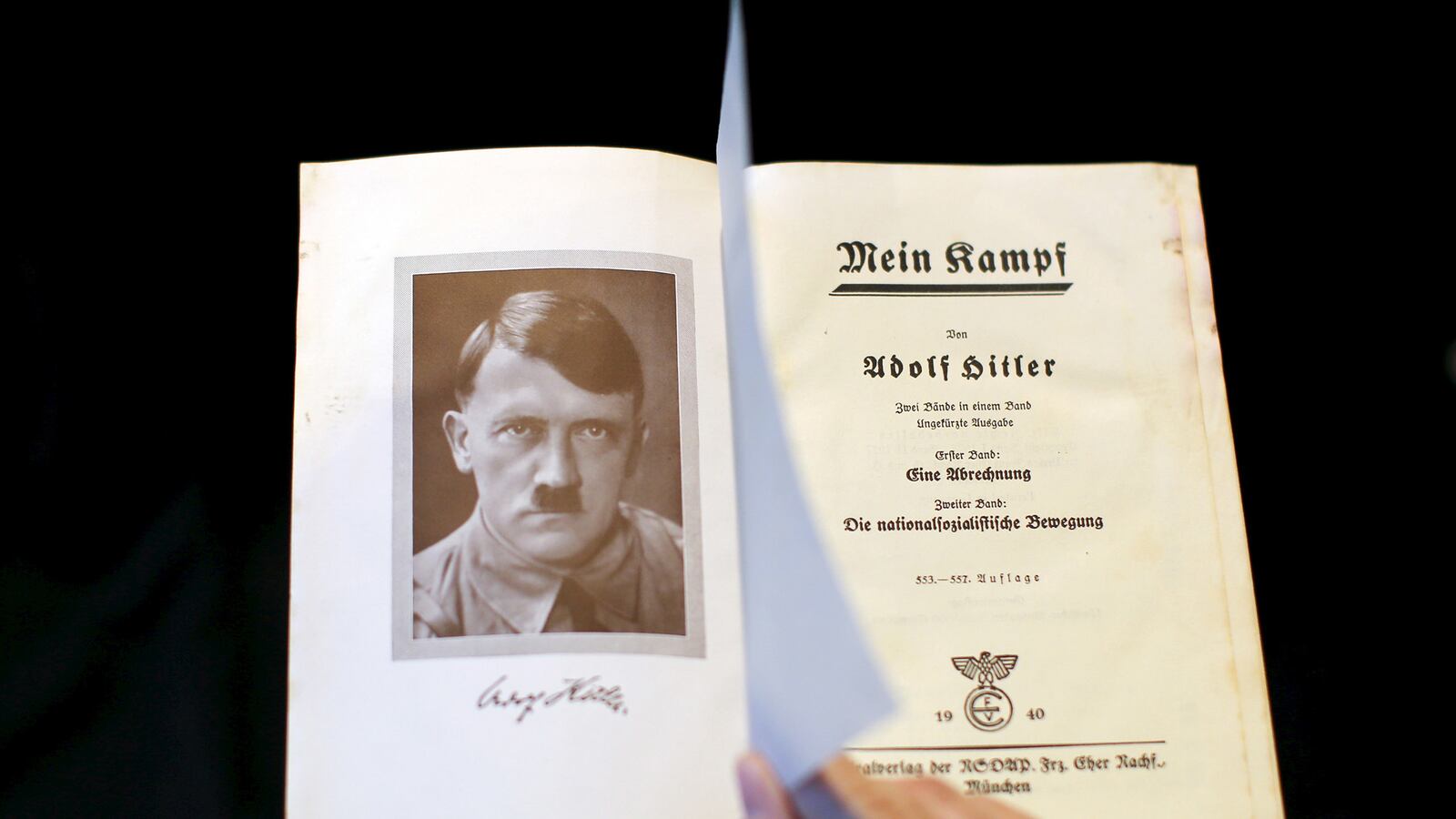

MUNICH — Who hasn’t heard of Mein Kampf, Adolf Hitler’s infamous Nazi screed? The book laid the foundation for his Nazi ideology and the roadmap to the Third Reich. Mein Kampf (My Struggle) was Hitler’s preamble to war; it’s where he preached what he would later practice.

But few alive today have actually read it, especially in its original language. Because in Germany, Hitler’s book was banned from the end of the Second World War until January 1 this year. Now Germany’s Institute of Contemporary History is republishing it, and while this scholarly version is the first edition to go back on sale in modern Germany, it may not be the last.

But will it sell? Market forces may have a part to play in this, and right now the market is, to say the least uncertain.

“Nobody read Mein Kampf when Hitler was in power.” says Niklas Frank, and he should know. His father was Hans Frank, confidante of Hitler and the high profile Nazi Governor of Poland, responsible for the death of millions.

As the child of a major war criminal, Niklas Frank has few good words for Hitler’s Nazi manifesto. “When you were married you got a copy of this bloody book, but nobody, really, was interested in it.”

The new German edition of Mein Kampf is hitting the stores just now, 90 years after the first printing in 1926. The Munich-based Institute of Contemporary History has pulled together an annotated version of Hitler’s megalomanic diatribe, adding no less than 1200 pages to the already very bulky 800-page read. If the original was boring, this one may be very heavy going indeed.

That this new edition, like the first one, is printed in Munich, is no coincidence. The German state of Bavaria, of which Munich is the capital, has held the copyright to Hitler’s book ever since the war ended.

Munich, you’ll recall, is the place where Nazism was born and flourished. In this city, young Austrian-born Adolph Schicklgruber settled in 1913 when he was 24, and recast himself with the punchier surname of Hitler. After their foiled 1923 coup, the so-called Bierstube (beer hall) Putsch, the Nazis proclaimed Munich the “capital of the movement.” Because Hitler only left Munich to take his parliamentary seat in Berlin as Chancellor in 1933, his official residency remained here. That is how Bavaria managed to get the rights to the book and prevent any German copies from being published until January the 1st of 2016. Copyright in Germany expires after 70 years.

Niklas Frank told The Daily Beast he first read Mein Kampf when he picked up a German-language copy as a journalist in Namibia, many years ago. “There you can buy it in every bookshop,” he said.

As for this reprint, he sees no danger in it. “Brilliant idea, it should have been done years ago. A big part of Mein Kampf is boring, sometimes it’s even a little funny,” Frank sniggers. “When he [Hitler] describes how he started the National Socialist party for instance. As the name of the book suggests, ‘my struggle,’ he is always pretending to do or fulfill something or other.”

Munich is wealthy and beautiful and many of its people today fit that description. Men are attired in smart casual wear and women dress in coats with fur trimmings. They slowly parade the quaint little squares and shiny boulevards that make up the center of town. It looks like a classic children’s picture book; nothing is out of place. In the shop windows dirndl dresses and lederhosen are sold next door to specialized stores selling only tea or herbs. The Bavarian capital has always been affluent, even between the two world wars. It’s always crowded at the local Bierstube Hofbrauhaus, a place where tourists can mingle with locals and taste the regional beers. The brass band plays traditional folkloric music in its domed basement as people sit down at its long tables. Before the war, the Munich Bierstube was the place where Nazis held their meetings. Hitler himself passed by. But on the eve of the Mein Kampf republication, Buck, Preston, Kevin and Lena are at a table here near the brass band. The trumpet player is a member of their own band, in fact. The group meets here twice a year. Buck: “My grandfather was fighting as a GI and Kevin’s grandfather was in the SS, they were mortal enemies, and here we are!”

The personal stories of this gathering give the impression everyone’s family here is linked somehow to the war. Most of them grew up in Munich, or around it. Buck is from Dachau. “So every time someone looks at my passport they react. But because I’ve got dark skin nobody bothers me about it.”

Buck and Preston’s family histories are entwined with the war, because their grandfathers were American GI’s. Preston’s grandfather married a German girl and only separated years after.

Preston: “My grandfather married a German girl, I was born in the US but raised as a true German, so I get a perspective from both sides, that’s great.” Buck still wants to look for his American relatives at some point. His father never met his grandfather, the GI Frank Wootz, who impregnated his grandmother then went back to the family he had already in the States.

At the press conference launching the book, Mein Kampf’s new edition was introduced by Dr. Andreas Wirsching, director of the Institute of Contemporary History. “It would be irresponsible to let this convoluted version of inhumanity roam free without critical reference,” he said, explaining the purpose of the voluminous annotations. By “contextualizing and deconstructing” the original work, the Institute hopes to inoculate its readers against Nazism. “We published the book ourselves, without commercial intentions,” said Wirsching. “The purpose is to add to the demystification, to present the deadly racism in a critical way.”

But, at the same time, the Institute insists the book was not made for the classroom. “Nazional Socialismus is not to be reduced to Hitler alone,” said Wirsching. “I wouldn’t propagate a school version of our edition…. The problem with Mein Kampf is that it is not just a book, it’s a symbol.”

I any case, there is not much chance of this printed beast roaming free. The expiration of copyright means Mein Kampf can be reprinted, yes, but only with commentary. Versions without it remain banned because of Germany’s hate speech laws. At the Institute, a team of historians from the center and outside worked on the new format for three years. “We have a scientific approach,” said Wirsching. “Our library holds 200.000 books. Our archive is five kilometers long.”

The selling of Mein Kampf is not a strictly German but an international problem, said Wirsching. He showed a photo from New Delhi where US President Barack Obama’s book cover is featured next to Hitler’s. They look shockingly similar. “We have to avoid the book becoming an article for export. We will come up with a strategy to prevent that from happening.” But that strategy may become a matter of urgency, now that the initial edition was already upped from 4000 to 15,000 copies because of the demand.

Niklas Frank is not worried: “Everybody should read this crap,” he says. “We all know what came of it: completely industrialized mass murder. You don’t believe what you read, because you know Hitler was a mass murderer and people like my father helped him do it.”

That may be so, but at the beer hall there is still something that bothers Buck about the reprint: “It’s is the idea that the book is sold again, and people are making money because of it that I don’t like. Anyway, what’s being taught in school is different from what you learn at home. My mother’s father told me he cried when Hitler died, it was all he knew.”

Some people believe the toxic proclamation is still too dangerous to read. After all, it was once used to propagate Nazism in preparation for the brave new world called the Third Reich. What if an educational scheme fails to demystify Nazism and in fact, inadvertently, finds a new audience for its racist ideals? Niklas Frank says he doesn’t believe that’s possible: “Mein Kampf is only of interest to people who want to know more about history, or people like me who were born into a family of a big shot Nazi criminal. But it’s not an issue for a great debate or for people in the street to have conversations about.” In an official statement Dr. Josef Schuster, president of the Central Council of Jews in Germany, hesitantly embraced the scientific edition. He started by saying the council “is convinced” that the book “must remain prohibited.” But, he went on, “Unfortunately, it can already be purchased via the Internet and abroad,” and “knowledge of Mein Kampf continues to be important in order to explain National Socialism and the Shoah. Therefore we do not object to a critical edition, contrasting Hitler’s racial theories with scientific findings, to be at the disposal of research and teaching.” When books are banned and gatherings are outlawed, ideology does not lose its appeal. The forbidden offers its own attractions, especially to the young.

At the Hofbrauhaus table of friends, Kevin said his grandfather, who served in the SS, always had “strange ideas” about the war. “When Hitler came to power he was only 13 and he was 25 when it ended. My grandfather owned a copy of Mein Kampf with gold inlay and a personal signature of Hitler. That book is now worth a fortune on the black market because Neo-Nazis love that rubbish. For them it’s like a Bible signed by Jesus.”

Angela Merkel’s ruling Christian Democratic Union government argues that giving Nazism a context and bringing it into the classroom would be a productive effort to nip the lure of Neo- Nazism in the bud.

Alexandra Senfft, an author and Middle East expert, became acutely aware of her own family history only later in life. “My family didn’t talk about the war. I knew my grandfather was the Third Reich envoy in Slovakia, so he was in an upper level of Nazi leadership. I later found out he was co-responsible for the deportation of 65.000 Slovakian Jews, most of whom died in the camps. In her book, Silence Hurts, she says, “I investigate the trans-generational consequences of guilt and the Holocaust and war though my grandmother, mother and me.”

Where does Hitler’s tome fit into that picture. “By all means look at Mein Kampf and contextualize it,” says Senfft. “It is part of our history. What I am kind of hesitant about is identifying Hitler as Nazism as such. I find it much more important to not only focus on leaders but on how people on an every day level, ordinary people, latch on to the ideology.” One must ask, she says, why “the majority of ordinary Germans became perpetrators.” But, she adds, “It helps to understand how words, publications and how you’re educated can actually prepare you.”

Giving Mein Kampf a well-founded historical context may be a well intentioned plan. But what happens if you lose that battle for the hearts and minds? What if, by introducing the book, you inadvertently introduce the seed of evil, and even help it to grow?

In the US, Adolf Hitler’s 800-page rant has been freely available since 1998. That hasn’t made Nazism more prevalent in America. OK. But according to the 2014 figures of the German Security Services, Germany harbors around 21.000 right wing extremists of whom 5,600 are Neo-Nazis. Will there be more now? How will reaction to the refugee crisis mix with Hitler’s bible of hate? Nobody has the answer yet.

And, in the meantime, how does one promote a book like that? “You don’t,” says the information clerk at a branch of the major German bookstore chain Hugendubel. In the shop there are no indications that the book is being sold at all. “We only sell them by pre-order,” he says. they’ve had quite a few requests so far, he says. “But you never know how long that will last. It was in the news yesterday, today people come asking, who knows what will happen tomorrow?”