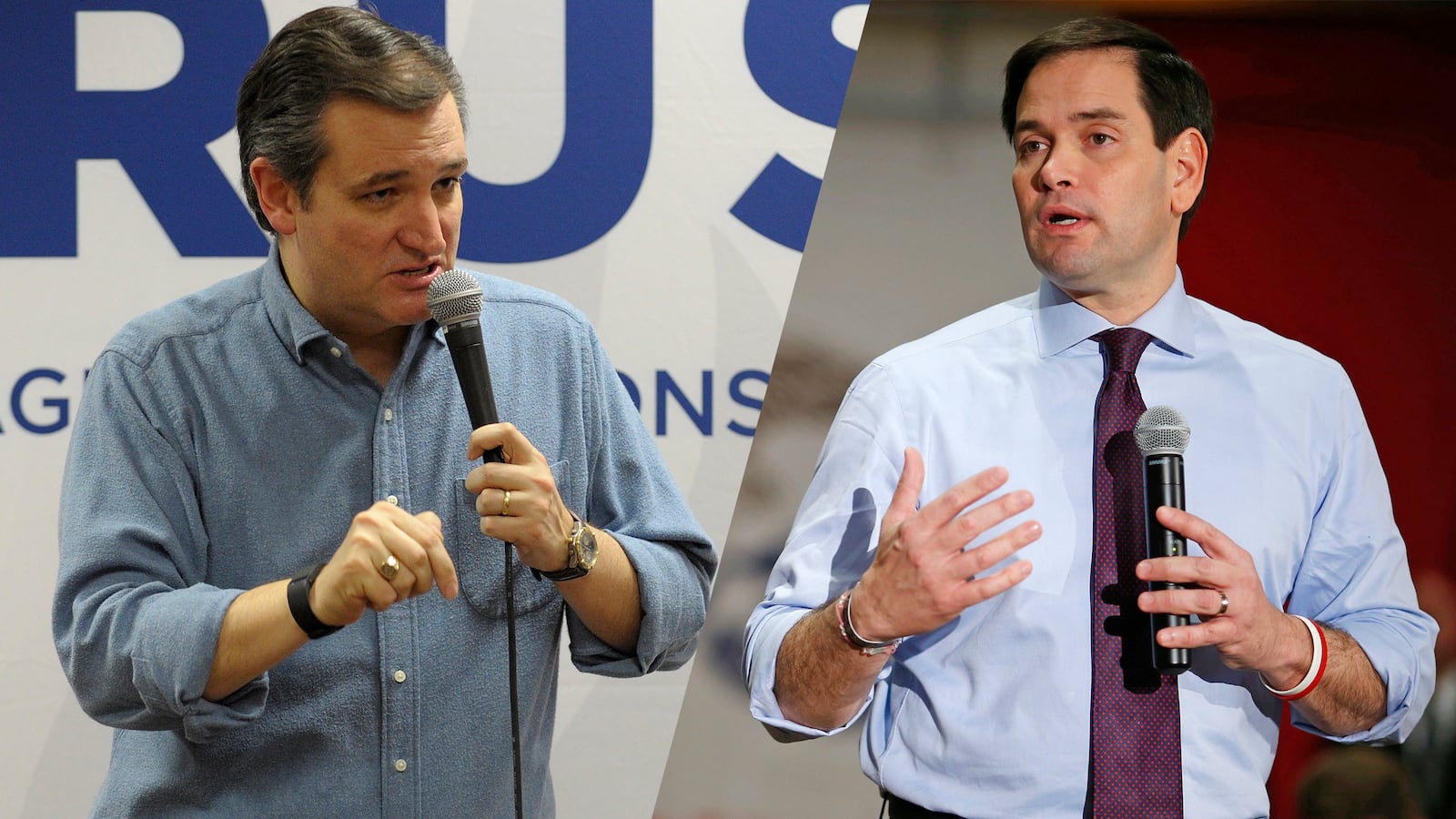

If Broadway producers do a remake of West Side Story with an all Cuban-American cast, they ought to cast Ted Cruz and Marco Rubio as rival warlords of the Sharks and Jets.

Clearly, the Republican Party’s Cuban-American superstars are ready to rumble—with each other. Rubio said last week on the Hugh Hewitt radio show that Cruz is his friend and that “we’ll be friends after this campaign.”

I’m not so sure. This is no friendly difference of opinion. This is blood sport.

These two GOP presidential hopefuls have a lot in common. Both are children of immigrants and about the same age (Cruz is 45, Rubio is 44). Both are first-term senators who were elected on the steam of the Tea Party. Both are smart lawyers and gifted communicators. And they’re both running not just for the GOP nomination, but for support from Latino Republicans all over America.

Perhaps this is why the rhetorical skirmishes that erupt every time they’re in the same room aren’t just politics as usual. They seem personal. They’re not about differences in what each man believes. Indeed, there is not much daylight there. It’s about what kind of man each thinks the other is.

Rubio thinks Cruz is a liar. He made that clear in Thursday night’s debate after Rand Paul went after Cruz for changing his view on whether the undocumented should be given an earned path to citizenship.

“This is the lie that Ted’s campaign is built on, and Rand touched upon it—that he’s the most conservative guy, and everyone else is a—you know, everyone else is a RINO,” Rubio said. “The truth is, Ted, throughout this campaign, you’ve been willing to say or do anything in order to get votes.

Cruz thinks that Rubio is a phony. So he responded:

“You know, I like Marco. He’s very charming. He’s very smooth. But the facts are simple. When he ran for election in the state of Florida, he told the people of Florida, “If you elect me, I will lead the fight against amnesty…Marco made the choice to go the direction of the major donors—to support amnesty because he thought it was politically advantageous.”

This telenovela has been going on for a while.

During an appearance a few weeks ago on NBC’s Meet the Press, Rubio jabbed at Cruz for decrying Donald Trump’s “New York values”—which Cruz describes as “socially liberal, pro-gay marriage, pro-abortion, focused on money and the media”—while continuing to collect money from New York donors and taking out a seven-figure loan from Wall Street investment and banking firm Goldman Sachs.

But Cruz also has a story to tell, and he doesn’t have any more respect for Rubio than the Florida senator has for him. It’s obvious that Cruz thinks Rubio is too close to liberals, too willing to work with Senate Democrats, and too wedded to the Republican establishment.

At some point, this Cuban-American standoff will have to be resolved. Of course, the conventional way of doing that is to go state by state, and let Republican voters choose their nominee.

But there is another “primary” between these two—the one for bragging rights over who wins the lion’s share of support from Latino Republicans, a group that represents about 20 percent of the Latino electorate.

There, things get complicated in a hurry.

For one thing, there is the age factor. So-called YUCA’s (Young Urban Cuban Americans) have been subtly declaring their independence over the years and shown a willingness to break with the right-wing views of their parents and grandparents. Often, they simply vote for the person they like best. Politically, they’re fluid. In fact, I know a lot of young Cuban-American Republicans who voted for Barack Obama in 2008.

Also, the Cold War is a historical footnote. If you mention “The Castro Brothers” to this group, they’re likely to think you’re talking about Joaquin and Julian, the Democratic rock stars from San Antonio. Indeed, surveys from Florida International University indicate that younger Cubans are much less hawkish, particularly when it comes to our dealings with Havana, than their elders. In any case, both Cruz and Rubio opposed the lifting of the Cuban embargo by the Obama administration. So this won’t be an issue one way or another—either for younger voters, or older counterparts. It’s a wash.

Then there is ideology. If the Latino Republican vote comes down to who is the more dependable conservative, the nod will go to Cruz. But if this group cares more about which candidate identifies more with his culture and will probably do more for Latinos in the long run, it’ll be advantage Rubio.

And then comes values. As I’ve written, Cruz thinks America is about freedom, while Rubio believes the nation represents opportunity. If Latino Republicans feel committed to the first principle, they’ll be drawn to Cruz. If they’re inspired by the second, they might well support Rubio.

Finally, there is geography. Latinos on the East Coast—in New York, New Jersey, Virginia, Georgia, Florida—are likely to identify with Rubio. Cruz will probably have a strong turnout among Latino Republicans in Texas. But it’s hard to see where he could expand that support beyond the Lone Star State.

In the final analysis, you’d have to give Rubio a slight edge overall in appealing to Latino Republicans. He’s likely to beat Cruz by as much as 2-1 with that group. But Cruz will return the favor by outdoing Rubio with white voters, who are not exactly in short supply in the Republican primary.

It’s not unlike another famous standoff in American history that has been brought to life and modernized by playwright Lin-Manuel Miranda in the new hit Broadway musical, Hamilton. In July 1804, after years of butting heads and thwarting one another’s ambitions, former Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton and Vice President Aaron Burr met on the dueling grounds at Weehawken, New Jersey, to settle the matter once and for all.

In the modern vernacular, you could say that Hamilton and Burr came together to see who was el mas macho.

As Miranda told CBS’ Charlie Rose recently, Burr had always envisioned the story would end in such a fashion. Miranda recalled that Burr had, before the duel, written in a letter: “There was no way this could have been avoided. We have been circling each other for a while. It was always going to come to this.”

These days, in the era of Cruz and Rubio, when differences need to be resolved, there are no more duels. There is only politics. A less humane alternative, to be sure.