In an almost impossible turn of events for a film that opens with such macabre wish fulfillment—in the opening moments, Justin Bieber is brutally assassinated in a long, graphic scene—Zoolander 2, critics agree, is really, really ridiculously bad.

Of course, this is a sequel to Zoolander we’re talking about, a film that, back in 2001, satirized the fashion world and celebrity culture with all the subtlety of an Alexander McQueen leopard print trench coat. Absurdity was the film’s hottest accessory then, and it was flaunted with all the deranged confidence of a male model strutting the catwalk.

Perhaps, then, expectations should be managed.

But mixing and matching parody and satire is a precarious styling trick, one susceptible to garish clashing if not done with a careful eye for taste. In Zoolander 2, taste goes out the window. In addition to being largely unfunny and uninspired, as my colleague Jen Yamato wrote in her review, the film is also horribly offensive.

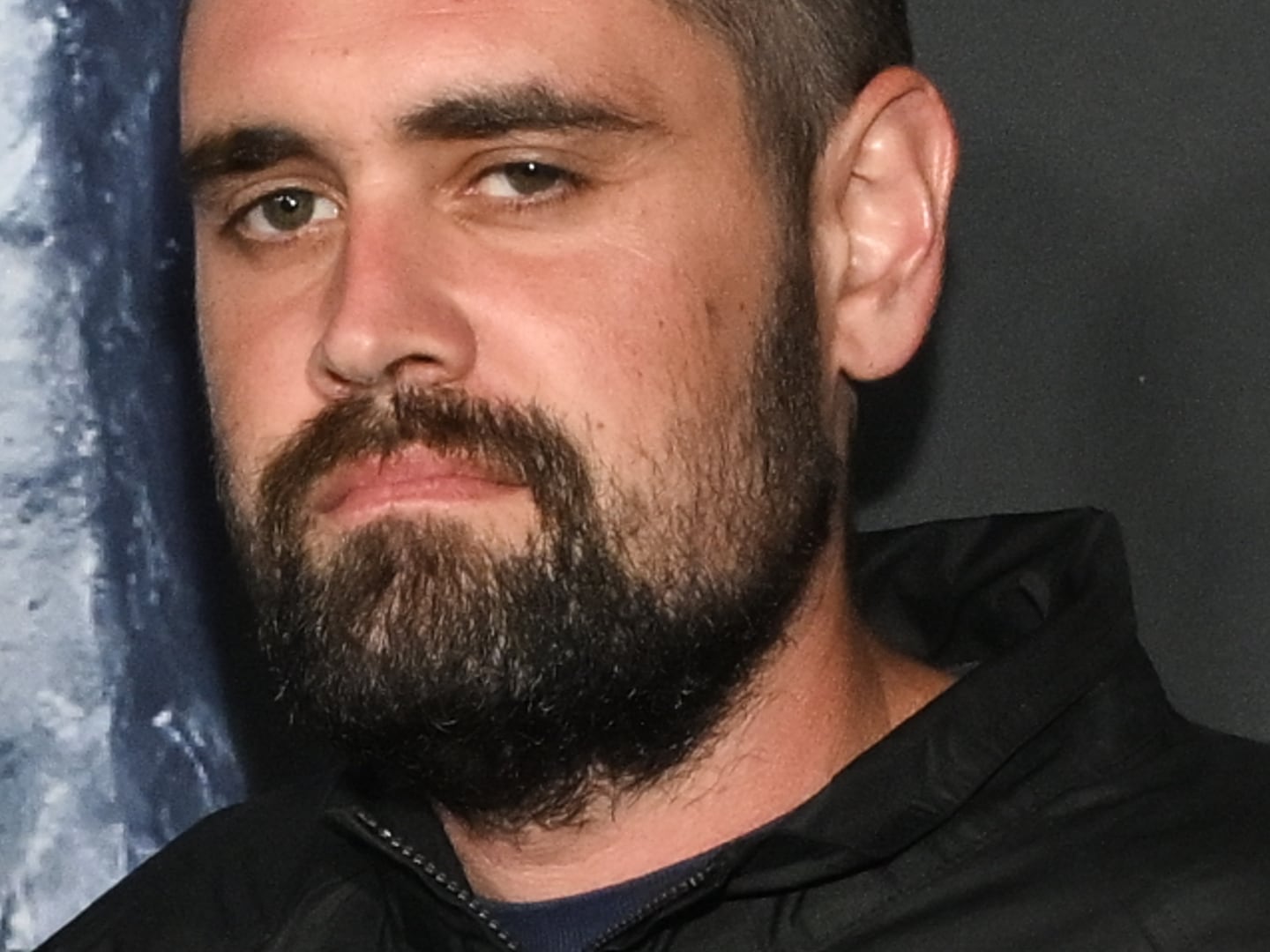

While making arguably sharp and perceptive observations about obsolescence, the farce of celebrity, and aging in the public eye—we’re being generous here—the film’s take on the LGBT community and, specifically, its handling of an apparently trans or androgynous character played by Benedict Cumberbatch is as clueless as our hero Derek Zoolander himself.

Concerns over Cumberbatch’s character, the industry’s hottest new model named “All,” first emerged when the film’s trailer was released, teasing jokes about the character as one of the film’s comedic highlights.

Presumably the character of All is a nod to the rise of androgyny in the fashion world, a transgressive and peculiar trend that has driven conversation in the culture-at-large.

Upon meeting All, Ben Stiller’s Derek Zoolander and Owen Wilson’s Hansel—who have spent over a decade away from the fashion world and apparently missed the evolution of trans and androgyne acceptance through various half-baked, high-concept plot conceits—are mystified.

“Are you, like, a male model or a female model?” Zoolander asks. “All is all,” All replies.

Hansel butts in: “I think what he’s asking is whether you’ve got a hot dog or a bun.”

It devolves from there. “Do you have a wiener or a vaginer?” A reference is made to All’s most recent sociopolitical act, marrying “hermself.” When the three models hit the catwalk, All is suspended from the sky like a terrifying gargoyle with wings and begins whipping Zoolander and Ansel. Cowering in fear, they shout, “Hot dog! Definitely a hot dog!”

All is dominant, so All must be a dude. Get it?!

When the scene was revealed, sans context, in the trailer, reactionary outrage dutifully exploded, the way our Internet culture of controversy encourages. A boycott of the film was called for, arguing that the “cartoonish mockery” of the trans, androgynous, non-binary community was “the modern equivalent of using blackface to represent a minority.”

The boycott was, and still is, as my colleague Tim Teeman wrote at the time, premature and arguably counterproductive.

The film had yet to be seen—final judgement should be reserved—and the policing of content and comedy is dangerous in its own right, especially considering the tradition of LGBT activism as a conduit for opening up discourse and debate about culture, particularly identity and our relationship to it.

Now that we’ve seen the film and reviewed the context of the scene, it’s safe to judge its merits and its values.

The crime here may not be overt transphobia (though we can’t fault anyone who finds danger in the debasing and ridicule of a population that continues to be threatened by violence fueled by a lack of acceptance and understanding).

In our eyes, though, the crime is excessive dumbness.

No malice is expressed toward All, but All's existence is the butt of jokes. Lazy jokes. Dated jokes. Really, frigging stupid jokes.

Giggling like schoolboys over whether a non-gender-conforming character has a penis or a vagina, employing such playground vocabulary as “hotdog or bun,” is exhaustingly retrograde.

Sure, no minority or population, particularly one at the center of a vibrant and essential cultural and political conversation, should be immune from comedy. Comedy is often the greatest catalyst for change and advancement. But we should be allowed to mandate that the comedy is intelligent or at least valuable.

Particularly in a farce set in the hotbed of ridiculousness that is the world of fashion, there is ripe opportunity for comedy as social commentary on the commoditization of trans and androgynous models.

Given how brilliantly the first Zoolander film both skewered and celebrated the self-seriousness and the relevance of fashion’s holier-than-thou players, it was even thrilling to think of how the sequel might lampoon the industry’s evolution in the last 15 years and the figures it now welcomes and, arguably, exploits.

What we got instead are cock jokes. (For what it’s worth, cock jokes that no one in my screening could muster the energy to laugh at.)

We’re not faulting Zoolander 2 for “going there.” We’re faulting it for wasting an opportunity. Expect activists to wield their pitchforks with cries of transphobia when the film hits theaters this weekend. And blame the film for not shielding itself from such accusations with comedy that has any redeemable value.

As a culture, we’ve become conditioned to take offense with every damn thing. It’s a discussion that set fire when Ricky Gervais was accused of transphobia for his Caitlyn Jenner jokes at the Golden Globes, and then attacked those who were offended by them.

Political correctness, perhaps once meant to be a safeguard against hateful speech, is now a weapon against free speech and the kind of conversation that moves a society forward.

Still, there’s a responsibility for being, well, responsible in the way we discuss things, particularly in the world of comedy. The trans community shouldn’t be immune. But we should demand the same quality control and, again, responsibility from these jokes as we would those about any population.

When you boil it down, all Zoolander 2 attempted to say was that the very act of being gender ambiguous—whether All was trans or androgynous or what have you—is funny. That curiosity over a trans person’s sexual organs is hilarious. Even if you set aside trans activists’ work to move the conversation away from such debasing things—which we would venture we shouldn’t do—the actual jokes in Zoolander 2 in that regard were just plain stupid.

Provocation is important. It causes discussion. But debate is best when it is intelligent. There was nothing intelligent about Zoolander 2’s trans jokes.

Are we putting too much importance on this? Maybe. But, hey, this is a film about the world of fashion. Putting too much importance on the fashion industry? Who’d ever heard of such a thing?