Those who have passed through the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s classical collection may recall some of the vases on display—the ones that feature naked women toweling off after a bath, pre- or post-coitus, or cozying up to some Adonis. A little porno-lite from ancient Greece as an aperitif to the Roman nudes.

One expects to see plenty of nudes at the Met, but few know that the museum is overrun by classy escorts. Indeed, the naked ladies decorating those ancient Greek vases were essentially upscale sex workers, known as hetaerae. They chose their male customers and were paid in gifts instead of money—the ancient equivalent of today’s sugar babies.

“They are the original courtesans,” art historian and professor Andrew Lear tells me during a preview of his “Shady Ladies of the Met” tour, an offshoot of the gay-themed Oscar Wilde Tours company he launched last year.

Lear’s private, two-hour tour takes guests from ancient Greece to 19th century America. His wealth of knowledge about the Met’s racier works—and memory map of the place—is well worth the $49 ticket price (fees vary for private group tours).

For a gay historian with a long background in the tour industry, showing people the Met’s hidden homoerotic art was an ideal gig. Then other themes caught his eye, like the images of women who were famous courtesans or royal mistresses.

The most famous ones were sexy and smart. They were beautiful, educated, wealthy, and upwardly mobile fixtures among the politically and culturally elite. As such, they were irresistible to kings, patrons, artists, and even philosophers. Pericles’s concubine Astasia is thought to have contributed to the teachings of Aristotle and Socrates.

After ancient Greece, Lear introduces me to one of Titian’s courtegiana: the Venus in his “Venus and the Lute Player.” In mid-17th century Italy, music was associated with upper class women and courtesans. In Titian’s painting, a nude Venus reclines on a sofa-bed with a flute in her hand—a clear giveaway that the woman depicted was a courtegiana.

“Respectable, upper-class women certainly didn’t play the flute in the nude,” Lear says with a suggestive smile. “We know Titian had a great relationship to the courtesan culture—that he dined with famous courtesans and that they addressed poems to him,” he adds. “But he probably didn’t have sex with them because they weren’t rich enough.”

Lear occasionally strays from “Shady Ladies” to point out a few of the museum’s “Sexy Secrets” (he offers a separate tour of these outliers in the Met’s staid collections), like Chiari’s “Bathsheba at Her Bath.”

Artists in Christian societies needed a religious excuse to paint vaguely erotic images. The biblical story of Bathsheba was frequently evoked, though “Bathsheba was not as important as art would suggest,” Lear says. In Chiari’s painting, Bathsheba is nude and her maid’s left breast is inexplicably exposed.

Later, in 18th century France, we see a portrait of Madame de Pompadour, mistress of Louis XIV, in François Boucher’s “The Toilette of Venus.” De Pompadour commissioned several paintings by Boucher and other major artists. (Lear believes she was likely the largest art patron in France at the time.)

We also see a late 18th century portrait of the English courtesan Mrs. Grace Dalrymple Elliot, commissioned by her aristocratic lover, and one of actress Elizabeth Farren.

“The distance between actress and prostitute was not that great in 18th century England,” says Lear. But Farren did eventually marry well (she became a countess), which wasn’t uncommon for courtesans. While ballet dancers weren’t exactly courtesans, they still had wealthy patrons (one lurks in the shadows of Degas’s “Dancers, Green and Pink”).

Courtesans in 19th century art were more overtly sexual, as with Courbet’s “Woman with a Parrot.” Her airbrushed body made her less scandalous than Courbet’s more realistic nude bathers, which were deemed unacceptable by the academy.

More scandalous was a portrait of a married woman with the strap of her dress hanging down around her arm: Sargent’s “Madame X.”

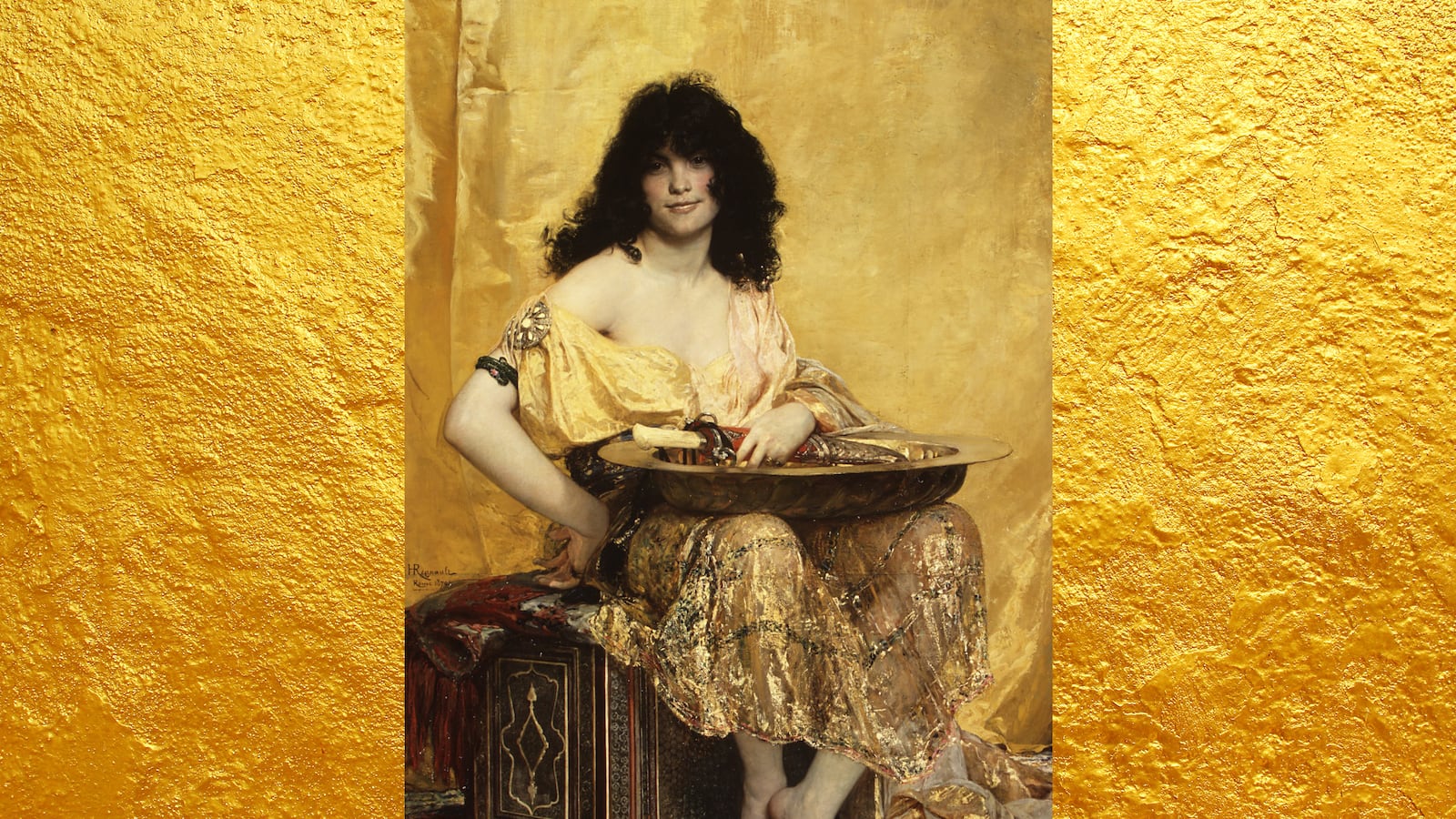

We finish with Henri Regnault’s “Salomé,” an exotic-looking woman whose hair is suggestively tousled, her breasts spilling out of her shirt.

“And then there’s that bizarre smile,” Lear says, before leaving to greet his next client: Dr. Ruth. “I’m not sure what it means,” he adds, “but it’s certainly not anything a nice girl ever thought.”

Sign up for the “Shady Ladies of the Met” tour on Fridays, Saturdays, and Sundays.