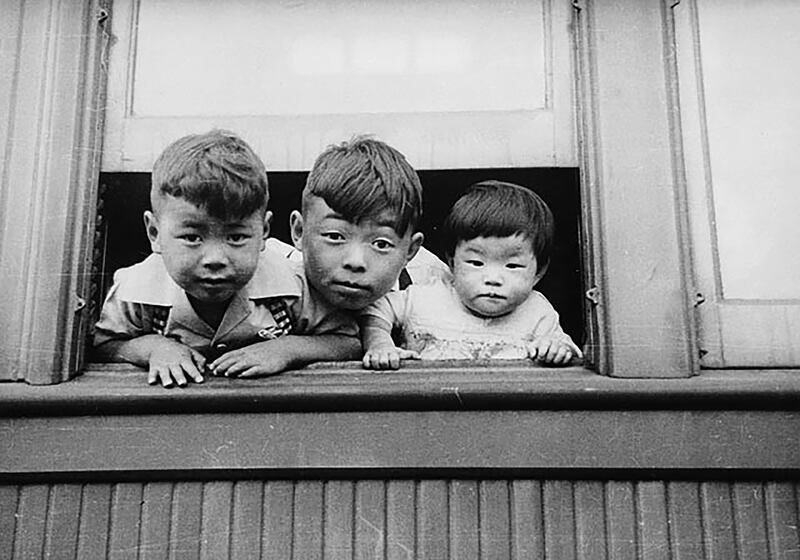

On the cover of Ken Adachi’s The Enemy That Never Was, the first book written about the Japanese Canadians and the wartime internment, is a close-up of a little girl’s face. She is only 5 or 6 years old, I would guess, maybe seven at the most. She is leaning forward and biting her lip, her intent gaze focused not on the camera but on something in the distance that we cannot see. I have always been captured by her expression: an ambiguous mix of anxiety and anticipation, uncertainty and curiosity. It’s a child’s face, full of innocence and sweetness, but darker shadows seem to hover around the edges of her mouth, as if the worried look of a much older person has begun to etch its traces onto her young face.

Although I don’t know who the girl is, I will confess I have been haunted by her image for a very long time. In the years leading up to the redress movement, I bought and read The Enemy That Never Was, and the book has been in my possession ever since. Every time I packed my belongings to move, every time I reorganized the books on my shelves, every time I touched this book, I would inevitably look at the cover and stare at the girl.

The full photograph from which the close-up is taken appears later in the book. It shows the girl surrounded by a crowd of Japanese Canadians who are waiting at a train station. Suitcases and boxes sit on the ground in front of them. The girl is leaning forward as far as she can, straining to look down the tracks, one imagines. Wanting to be the first to catch a glimpse of the train.

Without reading the caption, the contents of this picture seem obvious. In the aftermath of Pearl Harbor, Japanese Canadians were subject to mass uprooting and expulsion just like their Japanese American counterparts. They were forcibly removed from their homes on the Pacific coast and interned in remote detention camps in the rugged mountains of the British Columbia interior. Looking at this photograph you would naturally assume it shows a group of Japanese Canadians on their way to the internment camps in 1942.

But it is not.

For this is a photograph of the second uprooting, which took place after the war in 1946 when nearly 4,000 Japanese Canadians—close to one-fifth of the total population—were “repatriated” or deported to an impoverished and war-devastated Japan.

How did this happen?

In the spring of 1945, at a time when Japanese Americans were being released from the camps and allowed to return to the West Coast, Japanese Canadians were facing a very different fate. Racist politicians, who had long been calling for the deportation of all Japanese Canadians, increased pressure for a solution to “the Japanese problem.” Especially in British Columbia, where they were determined to purge their own province of the Japanese presence forever, they must have panicked upon hearing the U.S. Supreme Court ruling in December 1944 which effectively closed the camps and returned the right of freedom of movement to Japanese Americans. Canada and the United States may be two different countries, but they have always watched each other closely.

And so government officials devised the Canadian version of a “loyalty” questionnaire, otherwise known as the “repatriation” survey, which forced people to choose between only two options: move East of the Rockies and disperse, or go to Japan. Those who agreed to move East immediately and cooperate with the government policy of dispersal would be considered loyal and could stay in Canada. Those who signed an application for repatriation were labeled disloyal and would be deported when the war ended.

The option of returning home to the West Coast was not available. In fact, Japanese Canadians would not be allowed within 100 miles of the Pacific coast until April 1949, four years after the end of the war.

The harsh ultimatum was terrifying, and the camps quickly filled with panic, anger, confusion, and rumor. At the time of the survey, the war was still on, and no one knew when it would end. Some diehards fervently believed that Japan would win. Others feared that racism elsewhere in Canada would be even worse than what they had already encountered. All too often Canadian-born children found themselves torn between wanting to stay and being obligated to accompany parents who, for reasons of old age or poor health or sheer bitterness at having lost everything, wanted to repatriate. For many families who had been split up during the relocation, face-to-face discussion was impossible.

The survey was conducted with fierce efficiency and officials swept through the camps in only one month, forcing people to decide without adequate time or information and under enormous duress.

As if the prospect of moving to a distant, unknown locale were not intimidating enough, even worse was the insidious policy of dispersal. Japanese Canadians had to accept being scattered across the country. To refuse whatever jobs were offered, as one official notice bluntly stated, “may be regarded at a later date as a lack of co-operation with the Canadian government in carrying out the policy of dispersal.” They were warned never to form a community again as they had in pre-war Vancouver. For all the hardship entailed in living in the camps, at least people had always had each other for support. Moving east would change that. On the other hand, the government offered incentives to make repatriation an attractive and logical choice: free tickets for as many family members as necessary and no limits on the amount of baggage or cargo that could be taken.

Between May and December of 1946, five American transport ships set sail from Vancouver harbor carrying the deportees to Occupied Japan. Over half were Canadian citizens born in Canada, and of this group, one-third were dependent children under the age of 16. Could it really be said they were re-patriating if they were going to a country they had never set foot in before? Some spoke good Japanese, others barely a word. Almost all would have endured starvation conditions and painful discrimination as outsiders.

That was 70 years ago, and yet once again in some quarters we hear the ugly, irrational invocation of the word deportation, this time directed at other groups. It was wrong back then to target an entire people on the basis of ethnic identity. It is just as wrong today.

I look at the little girl’s face. She’s a stranger and yet she could so easily have been somebody one of my relatives might have known in the camps. I look at her face and I realize this: Had I been born earlier, she could have been me.

She could have been me.

She could be anyone of us.

A third-generation Japanese Canadian, Lynne Kutsukake worked for many years as a librarian at the University of Toronto, specializing in Japanese materials. Her short fiction has appeared in The Dalhousie Review, Grain, The Windsor Review, Ricepaper, and Prairie Fire. The Translation of Love, out now from Doubleday, is her first novel.