At Thursday’s Cannes press luncheon for Woody Allen’s new film Café Society, (which opened the festival on Wednesday), a journalist seated next to me asked the 80-year-old director what he thought of his son Ronan Farrow’s recent guest op-ed in The Hollywood Reporter.

A denunciation of the press’s “dangerous” blind eye to the continual accusations made by Farrow’s sister Dylan that Allen abused her, his own daughter, many years ago, Farrow’s article has become this week’s burning topic on the Croisette. An exasperated Allen replied: “I’ve said all I want to say about this in The New York Times. I’m so beyond all of this.” According to Variety, Allen’s curt response was an abbreviated version of a longer bout of exasperation prompted by a similar question at another table. “I never ever read anything,” Allen said. “I never read what you say about me or the reviews of my films. I made the decision I think five years ago never to read a review of my movie. Never read an interview. Never read anything, because you can easily become obsessed with yourself.”

And Laurent Lafitte, a French actor presiding as the master of ceremonies at the film’s premiere, quipped that it was nice that the guest of honor was making so many movies in Europe, “even though you are not being convicted for rape in the U.S.” Given that the joke is more cryptic innuendo than a bona fide knee-slapper, Allen proved rather gracious—a calculated move, from an optics standpoint—in defending Lafitte’s right to make any jokes he wishes.

Curiously enough, although these incidents have been characterized by some viewing the coverage online from the States as the “biggest story” so far at this year’s Cannes, many of the working critics at the festival have been inclined to shrug their shoulders. This apparently blasé stance has less to do with callous disregard of accusations of sexual misconduct than it does with a realistic, if seemingly cynical, assumption that film festivals, especially Cannes, should be categorized as what the late historian Daniel Boorstin termed “pseudo-events”—a peculiarly modern sort of feedback loop designed to generate publicity as well as manufacture “controversy.”

Cannes, albeit unofficially, does not view something like the Allen brouhaha as an embarrassment. On the contrary, the festival thrives on its ability to precipitate annual juicy scandals. One only has to glance back, although not perhaps wistfully, to 2011’s hyperbolic outrage after Danish director Lars von Trier made some gauche—although clearly tongue-in-cheek—comments about being supposedly “sympathetic” to Hitler. On that occasion, the festival definitely had its cake and gorged on it as well. They reaped the benefit of reams of free publicity while moralistically proclaiming von Trier “persona non grata.”

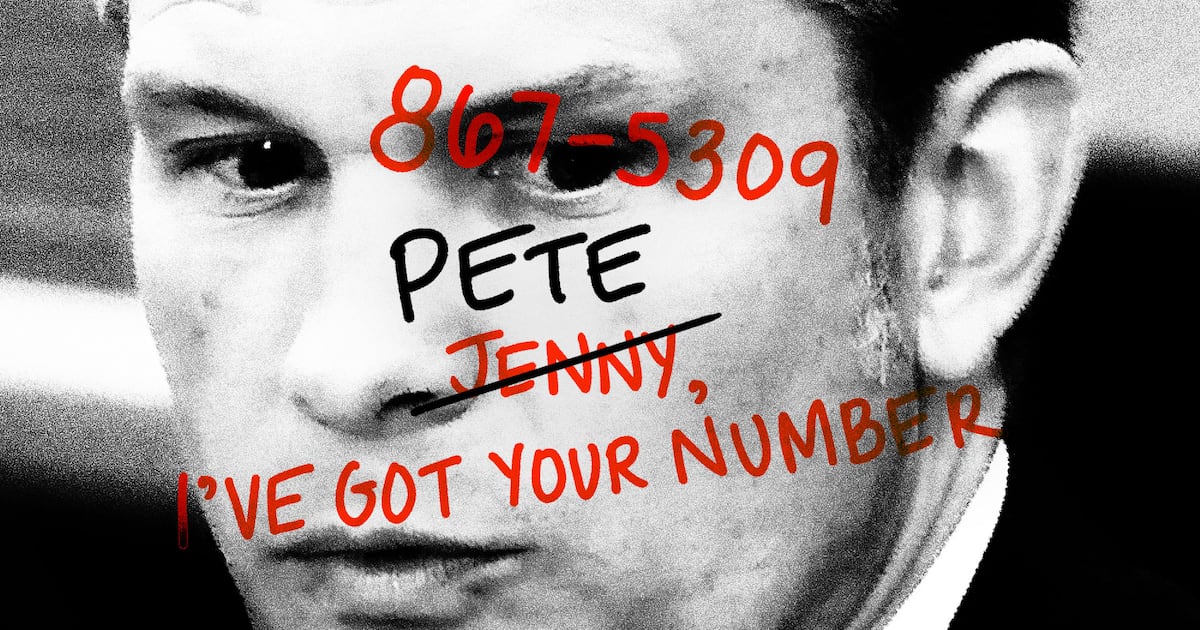

Within this framework, any attempts to discuss so-called ethical quandaries become subsumed by what has been called the “Cannes Effect”—an echo chamber in which the spectacle of scandal, and its guilty pleasures, can be enjoyed by one and all before we move on to the next outrage of the week. From this vantage point, the effort of RogerEbert.com’s Matt Zoller Seitz to pontificate about how his decision to “believe Dylan Farrow…contaminates” his previous reverence for Allen’s work comes off as merely banal. While it’s an unquestionably heartfelt piece, Seitz’s tortured reflections, as well as his choice to make a festival premiere the launching pad for them, ultimately capitulate to the lure of the Cannes Effect in which there is no such thing as wholly negative publicity and moral qualms become inseparable from salacious gossip.

And what about Café Society itself, the catalyst for all of these hyper-caffeinated rants? In truth, it’s a rather wan affair, an ambitious but ultimately failed tribute to classic Hollywood films of the ‘30s and, like other Woody Allen clinkers of recent vintage like Irrational Man and Magic in the Moonlight, a dispiriting exercise in recycling shopworn motifs from better films to little avail. Tried-and-true Allen themes such as May-December romances, Jewish neuroses and the threat of anti-Semitism, and the bicoastal rivalry of Los Angeles and New York are all regurgitated in a fashion that no doubt pleased the director’s many French fans. (Despite Lafitte’s barbed jokes, Allen was rapturously greeted with a standing ovation at the film’s premiere.) Even Bobby Dorfman, Jesse Eisenberg’s nebbishy protagonist, echoes Allen’s use of younger alter egos, ranging from Kenneth Branagh to Colin Firth, in equally weak ventures such as Celebrity and Magic in the Moonlight.

At the press luncheon, Corey Stoll, who plays a one-dimensional version of a Jewish gangster in the film, remarked that, when he was growing up in New York, Woody Allen and Philip Roth “reflected and defined” what could be termed an Upper West Side Jewish sensibility. It’s obviously nostalgia for the residue of this sensibility that allows many filmgoers to perpetually give Allen the benefit of the doubt, the mediocrity of his recent output notwithstanding.

To Allen’s credit, there are sparks of genuine ambition in Café Society. Instead of the awkward deployment of existentialist clichés in Irrational Man, Café Society, which takes place in Depression-era America, occasionally hints at a structure that resembles classic screwball comedy. Unfortunately, tired plot contrivances and anemic one-liners undermine hopes for a modern version of a Howard Hawks or Ernst Lubitsch comedy.

Essentially a coming-of-age story, Café Society pits Eisenberg’s naïve New Yorker Bobby against his uncle Phil (Steve Carell), a reptilian, name-dropping Hollywood agent who is on the verge of sabotaging his happy marriage by running off with Vonnie (Kristen Stewart), his beautiful secretary. In the meantime, Bobby, who works performing menial tasks in his uncle’s office, becomes infatuated with Vonnie and manages to successfully woo her despite her obvious fondness for Phil’s power and wealth. What little wit the film possesses is bound up with the protagonists’ mutual obsession with the charms of an elusive gentile goddess. When the impulsive, but practical, Vonnie spurns Bobby, this upwardly mobile macher returns to New York and makes a killing by operating an El Morocco-like nightclub with the help of his thuggish brother Ben (Corey Stoll). It’s difficult to care about the irony of Bobby ending up in a marriage to a blander, blonder version of Vonnie, another shiksa named Veronica played by the willowy Blake Lively.

Of course, as a filmmaker with 47 features to his name, Allen knows where to place the camera (it helps that the cinematographer is the legendary Vittorio Storaro, who captures both Hollywood Thirties glamour and the more humble environs of the Bronx with luminous virtuosity) and possesses consummate skill while directing actors. Most notably, a restrained Kristen Stewart, who is becoming an increasingly assured actress with each film, oscillates beautifully between surface vulnerability and self-confident pragmatism.

In the final analysis, however, Café Society is a supremely inconsequential film whose inflated importance at Cannes derives solely from its director’s celebrity. For some critics, the Romanian director Cristi Puiu’s Sierranevada, a competition entry that premiered on Thursday, is vastly more compelling than the trite Café Society. But, given the impact of the Cannes Effect on the international media, Puiu’s absorbing, three-hour talkathon is doomed to languish in the art house ghetto while Allen’s bauble will continue to bask in the glow of its director’s ongoing fame, even if that fame constantly threatens to congeal into notoriety.