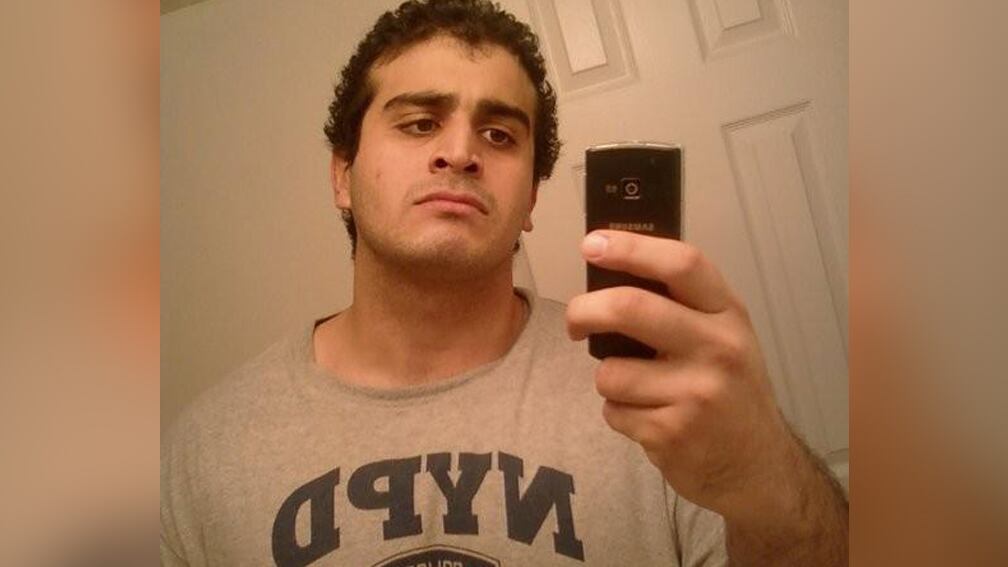

For nearly eight years before he embarked on a murderous rampage that claimed the lives of 49 people, Omar Mateen was employed as an armed guard by one of the world’s biggest private security companies, G4S. By some estimates, it’s the third-largest private sector employer in the world, with an armed force larger than some national militaries, operations in 120 countries, and more than 620,000 employees, some of whom are guarding U.S. embassies and consulates today.

And while no company that size could be expected to spot every problem worker, Mateen wasn’t the first G4S employee to act on his violent impulses with lethal results. Indeed, some employees’ violent histories, as well as the company’s own missteps on sensitive projects, had raised questions about G4S’s screening and hiring practices well before Mateen committed the worst mass-shooting in U.S. history.

G4S has contracts with the Homeland Security Department to provide guard services at U.S. government facilities. But its reputation among homeland security experts is mixed, said one former U.S. official who asked to remain anonymous in order to speak candidly about the company’s work.

“They have a reputation for doing work at the lowest price that’s still technically acceptable,” the former official said. “Think of it as a security version of McDonald’s. The feeling is that they’re cheap.”

G4S famously bungled a contract to provide thousands of guards for the London Olympics in 2012. Thousands of British Army troops had to be brought in to fill the gaps.

But that was only the most visible of G4S failures. According to numerous published reports, court documents, and government investigations, the company has employed security guards who abused children, murdered co-workers, and has relied on Afghan warlords to provide security for U.S. military personnel.

“Frankly, a lot of people have worried about both the quality of their employees and the clearability,” the former official said, meaning the ability of G4S personnel to pass background checks intended to discover past criminal behavior or potential future trouble.

A G4S spokesperson said in a statement late Sunday night that Mateen had twice been subjected to “screening and background checks,” first when he was recruited in 2007 and then again in 2013. The first check “revealed nothing of concern,” and the second check resulted in “no findings,” said Monica Lewman-Garcia, G4S’s director of communications.

And yet during that time, Mateen was twice visited by FBI agents who were investigating his potential ties to terrorists.

“In 2013, we learned that Mateen had been questioned by the FBI but that the inquiries were subsequently closed,” Lewman-Garcia said. “We were not made aware of any alleged connections between Mateen and terrorist activities, and were unaware of any further FBI investigations.” In 2014, Mateen was questioned again about his ties to an American man who joined ISIS in Syria, where he became a suicide bomber.

Mateen was listed on two U.S. government watchlists, one a classified list and another less sensitive one that’s maintained by the FBI. The store where Mateen bought the weapons used in the massacre at the Pulse gay club in Orlando was required by law to check his name against that second list, a U.S. official told The Daily Beast. However, Mateen’s name was removed from it in 2014, the official said, which means that the gun background check would have turned up no record of his being on an FBI watchlist.

Yet G4S had been aware for approximately three years by the time Mateen began his killing spree that he’d been on the FBI radar. Mateen also had a gun license by virtue of his work as a security guard.

The company hasn’t specified how they became aware of the FBI’s initial investigation, nor whether company personnel further questioned Mateen about why law enforcement had been speaking to him. The Guardian reported Monday that the FBI had interviewed Mateen after he said he knew the Boston Marathon bombers, a claim that the bureau later determined was false. But whether G4S knew that one of its guards was making wild and unfounded claims is unclear.

Lewman-Garcia didn’t respond to a request for comment about the FBI investigations and what steps, if any, G4S took when it learned of them.

G4S has a long history of working for the U.S. government. The company provides guards to the Homeland Security Department and the Federal Protective Service, the department’s police force. Within the past year, the company has won contracts totaling more than $61 million to provide guard services at U.S. embassies and diplomatic missions in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Singapore, Bangladesh, and Austria, according to federal contract records.

G4S also works with the Immigration and Customs Enforcement bureau to transport illegal immigrants in the U.S. The company boasts in an online brochure, “Annually, our G4S fortified buses log millions of miles and transport hundreds of thousands of illegal immigrants, while freeing up front line [Customs and Border Patrol] and ICE personnel for other essential services.”

The company says its other U.S. government customers include the Drug Enforcement Administration, the Justice Department, the Air Force, the Internal Revenue Service, and NASA.

G4S has also provided security for the U.S. military, but not without serious problems. In 2008, ArmorGroup, a subsidiary of G4S, provided security for a U.S. airbase in Afghanistan. Initially, the company drew its staff not from cleared U.S. employees, but largely from a “succession of warlords,” according to a 2010 investigation by the Senate Armed Services Committee, “and the guards affiliated with them [were] implicated in murder, revenge attacks, bribery, and anti-coalition activities.” ArmorGroup was paid $5.1 million per week for its work, the committee found.

While the vast majority of the company’s personnel seem to work without incident, some have acted out violently in ways alarmingly similar to Mateen.

In 2009, a G4S employee working in Baghdad sent an anonymous email to the company’s headquarters in London, warning about an employee named Daniel Fitzsimons, whom the informant claimed had been fired from a previous job after striking a client. “I am alarmed that he will shortly be allowed to handle a weapon and be exposed to members of the public. I am speaking out because I feel that people should not be put at risk,” the employee wrote, according to the BBC.

The anonymous employee sent subsequent emails which he said went unheeded by G4S. Fitzsimons later shot and killed two fellow employees and attacked an Iraqi. Fitzsimons was sentenced to 20 years in an Iraqi prison.

There have been other outbursts of violence by G4S employees. In Canada, a member of an armored car crew shot his fellow guards, killing three and making off with the money they had been transporting. (Protecting cash is one of G4S’s many lines of business, which also include performing background checks for other companies’ employees.)

A G4S guard in Scotland, who was working at a medical conference, beat a woman to death with a fire extinguisher after she reportedly complained about being asked to show her security pass.

And in Florida, where Mateen worked, two G4S employees have recently been implicated in crimes against children.

At the Palmetto Youth Academy in Manatee County, Leroy Bostic Jr. was arrested in 2014 on charges of sexually abusing two teenage boys.

At a facility in Tampa, Viviana Hernandez-Trejo was investigated for engaging in sex acts with a boy under her care.

An investigation in 2015 by Scripps Treasure Coast Newspapers found records documenting multiple assaults at youth-detention facilities G4S managed in Florida, both against the company’s employees as well as minors under its charge. G4S provides security for about 30 juvenile-detention centers in the state, according to the report.

“I’m amazed at the amount of violence that goes on over there, both against staff and other inmates,” Assistant State Attorney Vicki Nichols, Martin County’s juvenile prosecutor, told the newspaper, referring to a girls’ facility run by G4S that had a history of violent altercations among staff and children.

One of Mateen’s fellow guards said he had tried to raise alarms about the future-killer’s violent streak. Mateen was “unhinted and unstable. He talked of killing people,” Daniel Gilroy, who worked with him at a gated community, told Florida Today.

Gilroy added that he complained to G4S about Mateen’s odd, often bigoted, behavior—to no avail. Eventually, Mateen began stalking Gilroy, leaving him 30 or more text and phone messages per day, he said. Gilroy eventually quit.

(The Daily Beast contacted Gilroy but declined to interview him after he said he wanted to be paid for his information.)

While the vast majority of G4S employees appear to be low-level guards, the company also offers what it claims is a more sophisticated type of worker called a “Custom Protection Officer,” which it says are subjected to “psychological, background and criminal screening.”

It’s not clear what standards G4S used, and whether Mateen was screened using the ostensibly more stringent criteria that the company says it applies to its elite guards.

But Mateen moved around to different jobs, and by the time he was pulling his last stint as a guard in a private golf-course community, he was unarmed, the company spokesperson said.

G4S still hasn’t answered questions about what led to his transfer—and whether it was imposed on him or if requested the move—and why he was given a job without a weapon. According to the Orlando Sentinel, he had previously worked as a guard at the St. Lucie County Courthouse in 2013, the same year he was first investigated by the FBI.

Mateen’s has told reporters that was unstable and beat her, and that at the time of their marriage, from 2009-2011, he worked at a juvenile detention facility near their home.

A spokesperson with the Florida Department of Juvenile Justice declined to answer any questions about Mateen’s employment and referred all inquiries to G4S.