As kids in the ’60s, my siblings and I invented a Father’s Day ritual. Early in the morning, we laid sheets of paper end-to-end on the floor of our home, making a winding path that led from one room to the next, the paper marked with clues: directional arrows and big hints (“Look in the closet”). When our father awoke, we instructed him to follow the path and watched with gleeful satisfaction as he stepped slowly, deliberately, pausing occasionally—“What a long path! Do I have the strength to continue?”— and finally made it to the end, where his present awaited. A razor and can of shaving cream? A tie? A handmade card signed by all of us children? I don’t remember the gifts. I remember the path.

A few days before Christmas 1973, my father took his own life. He was 44. I was 14. He left behind a wife and eight children and no note to explain himself. Still, his final act was not a complete surprise. He was a successful, hard-working CPA with a sharp and goofy Irish wit, but he was in the habit—like many men of his generation—of keeping his problems to himself. He did not speak of how, in his childhood, he had suffered a series of wrenching losses, beginning with the loss of his father, who abandoned the family and vanished before my father could walk. In his last years my father was increasingly unhealthy, both physically (he had diabetes and was not always diligent in treating it) and mentally. In his last few months, he was like a ghost in the house. I rarely saw or spoke to him.

As the decades passed and his death grew more distant, so did he. My father calcified into splinters of memory that I could not make cohere. He lay still within me, in shadows, the vague shape of a man I had known when I was 8 and 10 and 13—in other words, a man I had known hardly at all.

Then, as I entered my late forties, becoming older than my father had ever been, the fact of his absence began to nag in a new way. Who was he, anyway? How had he come to be the sort of man who could kill himself, leaving behind a wife and eight children? What happened—in the years, the decades, the century—before his death that set the stage for it? I decided to write a book about him, compelled by a desire to break the silence within which he lived and died and to make, perhaps, some peace with his absence. I set down words on paper, marking it with clues, laying down a path, page by page, that might lead me to an understanding of why my father made the final choice he did. Having finished the book, I do think I have a better understanding of that act, but the most powerful and gratifying consequence of my writing is this: in imagining my way into my father’s life, I have come to feel closer to him than I ever did when he was alive.

My project was about remembering, but it was first about discovering. I pored over census records and newspaper archives and my father’s high school yearbooks. I studied old family photographs and letters. I drove through Seattle in search of addresses where my father had lived as a child. I traveled from my home in Indianapolis to East St. Louis and Litchfield, Illinois, where earlier generations of my father’s Irish immigrant family had labored on the railroads. I interviewed my mother and siblings and distant relatives whose existence I learned of only through detective work.

Then I pieced together the facts I’d gathered, trying to tell my father’s story, the one he never told me. On sabbatical from my teaching job, I had the leisure to spend whole days at the keyboard, contemplating my father at a particular age, in a particular moment: at seven, on a sunny September day in Seattle, playing with his two brothers on a lake shore, realizing that one of them, 5-year-old Skippy, has disappeared, then learning, after the sheriff’s bloodhound has done its work, that Skippy slipped off the dock and drowned; or, at 11, after the funeral of his mother, standing on the sidewalk outside of the church and asking his grandparents what is going to become of him—asking who is going to care for him now; or, at 16, at a high school mixer, being bold enough to ask for a dance, then one more, then one more, with the cute 14-year-old brunette who will one day be my mother.

I might end a day’s writing session having produced only 300 words, but I would have spent hours imagining a moment in my father’s life and existing with him in it. I wrote his story chronologically and thus began to have the uncanny feeling, day by day, paragraph by paragraph, that he was moving through his life and I was moving through it with him. He was no longer the middle-age suicide; he was alive again as the teenager strolling home from school, bounding up the wooden steps of his front porch. He was the 18-year-old marine at Pearl Harbor, discovered on a bright August morning asleep at his post. He was the young man, still in college, getting a phone call from a stranger—his long-lost father—whom he meets that night for a reunion conversation and then decides never to see again. My father did not live to accompany me in my journey through life, but I was accompanying him through his.

I began to feel sorry for the guy and to identify with him. After all, I too had lost a father when I was young. I too had become 16 and 20 and 35 and 40. I understand now what I couldn’t have when my father was alive. I know what it feels like to have a wife and young children and a complicated job that demands long hours of attention. I know what it is like to return home weary from work to gleeful shrieks of “Daddy! Daddy’s home!” and to feel warmed by those sounds, then slightly annoyed as my two small boys leap upon me or follow at my heels yammering of some project they need help with before I have had a moment to slip off my jacket and collect my thoughts. What was it like for my father to return home not to two children but to five or six or seven? I know what it feels like to have one’s marriage come to a breaking point. My first wife and I separated for a year, and I recall well my tangle of feelings in that sudden solitude: the dizzy mix of liberty and loneliness. Is that what my father felt when, late in my parents’ marriage, he lived for almost two years in a nondescript apartment a few miles from our home?

I wouldn’t mind talking with him about these things—and I have sometimes felt as if I could. In writing my book, I experienced moments of almost forgetting he was dead. About some impossible question regarding his life, I considered just asking my father directly, only half-realizing that this would be impossible. He was becoming that real to me, that alive—not the fixed, distant father of memory but a yearning, imperfect, strange, and changing person, as anyone is. In writing a sentence, then another, then another, I was following a path into the past toward a gift I didn’t expect and will never give back: not a feeling for why he died but a feeling for how he lived.

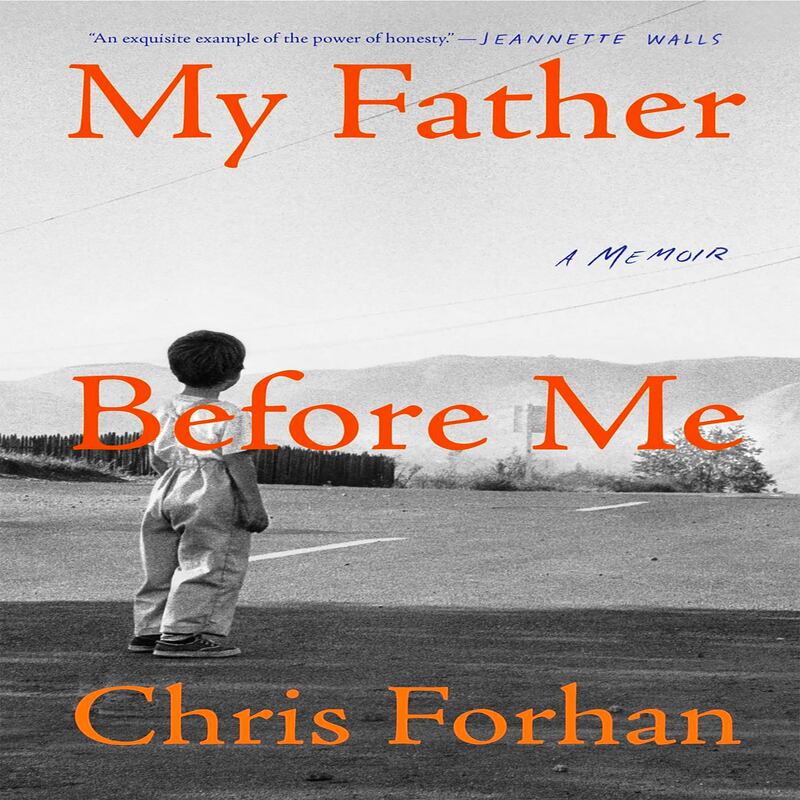

Chris Forhan’s memoir My Father Before Me will be published by Scribner on June 28.