This year Juneteenth—the annual June 19 commemoration of the end of slavery in America—comes at a time when the country’s racial tensions are once again headline news. How long they will remain headline news is unclear, but a new exhibit at the Art Institute of Chicago, “Invisible Man: Gordon Parks and Ralph Ellison in Harlem,” puts our present racial divisions in historic perspective.

The Art Institute of Chicago exhibit, which runs through August 28, combines the photography of Parks, who got his artistic start as a photographer for the Depression-era Farm Security Administration photo-documentary project and later gained added fame in the ’70s as a Hollywood movie director, and the writing of Ellison to offer a portrait of Harlem in the post-World War II years.

The exhibit, which comes with a catalog edited by its curator, Michal Raz-Russo, features two collaborations by Parks and Ellison. The first collaboration was a 1948 photo essay, “Harlem is Nowhere,” that was done for ’48: The Magazine of the Year and focused on the Lafargue Mental Hygiene Clinic in Harlem.

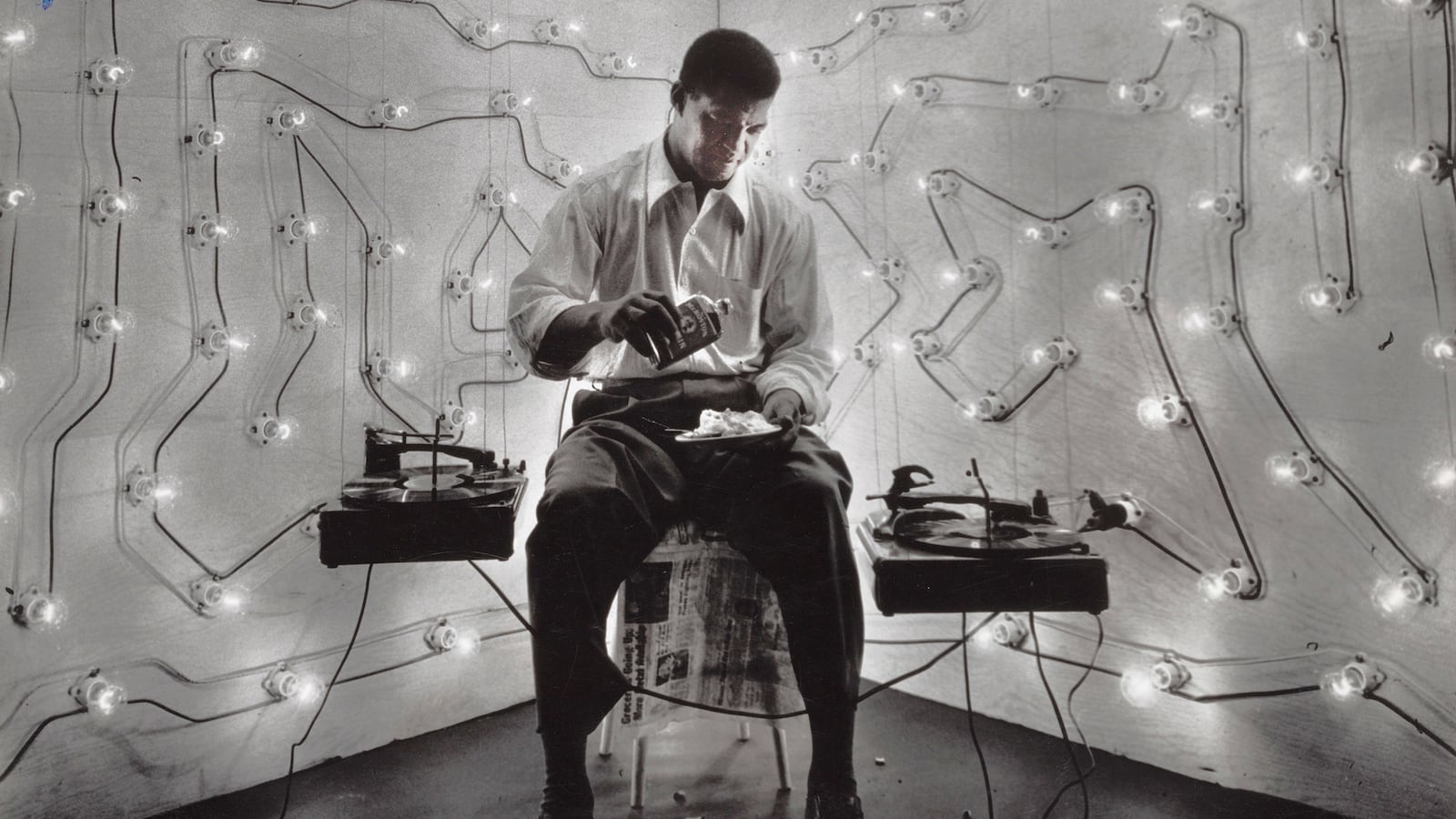

The second collaboration, a photo essay titled, “A Man Becomes Invisible,” was done for Life, where Parks became a staff photographer, and was based on recreating scenes from Ellison’s 1952 National Book Award-winning novel, Invisible Man.

“Harlem Is Nowhere” was never seen in 1948. The Magazine of the Year filed for bankruptcy and went out of business before the photo essay could be published. Ellison’s essay did not reach readers until 1964, when he added it to his 1964 essay collection, Shadow and Act, and Harper’s published an edited version of what Ellison had written.

“A Man Becomes Invisible” did, on the other hand, quickly gain an audience as a result of its appearance in the August 25, 1952, issue of Life, but “A Man Becomes Invisible” has long since been forgotten. Museumgoers will rightly feel that the Art Institute of Chicago has breathed new life into two neglected past projects by combining them in a single show.

Parks’s “A Man Becomes Invisible” photos, which include a picture of a young black man rising from a half-open manhole, are designed to capture the surreal aspects of the life of the hero of Ellison’s novel, an alienated African American living in Harlem. These photos show Parks operating at his most imaginative, and in the case of his manhole photos, they show him posing his subject.

By contrast, the haunting photos of “Harlem is Nowhere” are reality-based from start to finish. The Lafargue Clinic, which opened on March 8, 1946, in a church basement, was the first mental hygiene clinic in Harlem and was as much a reflection of social protest as it was a pioneering medical facility. In a New York City in which racial discrimination was rampant, the clinic offered the city’s black residents a unique chance for psychiatric care at a nominal fee (25 cents if they could afford it).

The clinic had come into being as a result of the collaboration of the novelist Richard Wright, the Reverend Shelton Hale Bishop, and the psychiatrist Dr. Frederic Wertham, who also became clinic director. At a time when there were only eight African-American psychiatrists in the United States, the clinic’s staff worked without pay.

Ellison’s text for “Harlem is Nowhere” captures the thinking behind the formation of the Lafargue Clinic. The focus of his text is on how the social conditions of Harlem are the source of many of its residents’ mental ills.

In a letter to the novelist Richard Wright, Ellison explained his thinking. “I am working on a piece describing the social conditions of Harlem which make the clinic a necessity,” he wrote. “I’ve worked out a scheme to do it with photographs which should make for something new in photo-journalism—if Gordon Parks is able to capture those aspects of Harlem reality which are so clear to me.”

“The phrase, ‘I’m nowhere,’” Ellison writes in his essay, “expresses the feeling borne in upon many Negroes that they have no stable, recognized place in society.” They are, he explains, caught up in a process of “chaotic change,” and the aim of the Lafargue Clinic is to help them come to terms with this change.

The Lafargue Clinic understands, Ellison goes on to say, that the personality damage so many in Harlem experience “represents not the disintegration of a people’s fiber, but the failure of a way of life.” As such, the Lafargue Clinic does not content itself with just offering its patients psychotherapy. It aims instead to give each “an insight into the relation between his problems and his environment, and out of this understanding to reforge the will to endure in a hostile world.”

Parks’s photos and the captions Ellison supplies for them emphasize this link between social disintegration and personal breakdown. Parks’s cityscapes show garbage burning in the street, people sleeping in doorways, a man lying unattended in the street after being struck by a car. Ellison comments on these scenes in unambiguous prose, observing at one point of the pain they cause, “To protect oneself from casual violence and to assert one’s individuality, one learns to turn one’s head.”

Even the photos of hope that Parks and Ellison offer are typically hedged with caution. One of the most revealing of Parks’s pictures shows a patient at the Larfargue Clinic holding his head in his hands with a caption below him that reads, “The Lafargue Clinic aims to transfer despair, not into hope but into determination.”

Today we are a long way from the Harlem that Parks and Ellison depicted in the post-World War II years or that the Metropolitan Museum of Art, under the direction of Thomas Hoving, sought to capture in a 1969 photo exhibit, “Harlem on My Mind,” which erupted in controversy because of the anti-Semitic comments contained in one of the essays from its catalog.

The current Harlem doesn’t suffer from the traditional neglect of the past. High-end housing is being built, new restaurants are moving in, 125th Street is thriving, and so is Harlem’s southern border, 110th Street, which fronts the northern end of Central Park. But the new gentrification of Harlem has brought with it its own set of problems.

As Harlem in the 21st century turns increasingly white and middle class, many of its black residents are finding they can’t afford to live there and that the city, even under an avowedly liberal mayor, is not providing them with sufficient help. They are becoming part of a Harlem diaspora, a fate that Parks and Ellison never imagined for themselves when they first moved to Harlem.

Nicolaus Mills is professor of American studies at Sarah Lawrence College and author of Like a Holy Crusade: Mississippi 1964—The Turning of the Civil Rights Movement in America.