According to conventional wisdom, Hillary Clinton’s VP pick, Senator Tim Kaine, is the boring, safe choice: uninspiring to progressives, a white dude, but a competent centrist from a swing state. Kaine said so himself on Meet the Press: “It’s true. I am boring.”

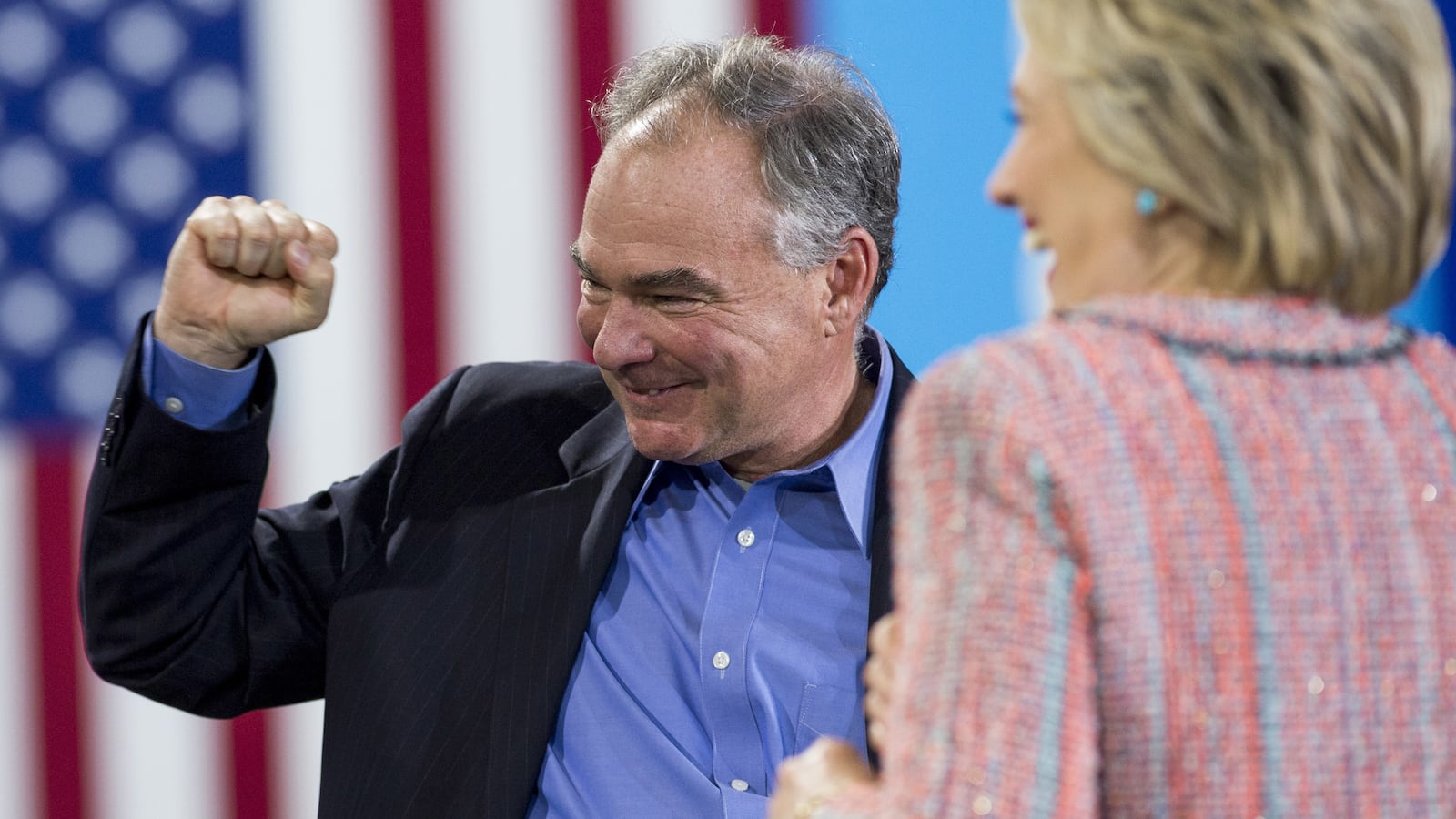

In a text message to her supporters just after 8 p.m. on Friday evening, Clinton wrote: “I’m thrilled to tell you this first: I’ve chosen Sen. Tim Kaine as my running mate. Welcome him to our team.”

Not quite. In fact, Kaine’s old-school, social-justice, Jesuit-trained Catholicism is a refreshing break from the usual association of religiosity with conservatism. As such, especially if Kaine does attract moderate Republicans disenchanted with the extremism of Donald Trump, he has the potential to be a transformative figure.

Like his potential predecessor, Joe Biden, Kaine reflects both the past and the future of the Catholic Church—but not the recent past. For a long time, mainstream Catholics emphasized the church’s social gospel: caring for the poor, opposing war and the death penalty, and so on. And with the series of reforms known as “Vatican II,” it seemed as though the church would keep pace with the times and moderate its doctrines on sexuality, gender, and birth control, while maintaining its basically liberal social justice outlook.

That didn’t happen. Instead, the sexual revolution caused the Catholic Church to turn rightward, retrenching on conservative teachings on sexuality and gender, and placing opposition to abortion at the top of the church’s American political agenda. Weirdly, Catholic teachings on life beginning at conception became adopted by American evangelicals (who had once bitterly opposed them) and the right-wing alliance between conservative Catholics and Protestants created the contemporary Christian right.

Not all Catholics went along, however. The Jesuit order, in particular, remained focused on service, justice, and issues of poverty, de-emphasizing (while not opposing) issues of sexual purity. Not surprisingly, Pope Francis, the first Jesuit pope, has followed this pattern, much to the chagrin of traditionalists. While not changing Catholic dogma, he has spoken of the need to apologize to gay people, and has washed the feet of poor people around the world.

That is Tim Kaine’s tradition, too. In particular, he has spoken often of the year he spent with Jesuit missionaries in Honduras, telling Charlie Rose in 2008 that “the transformative event in my life, next to being a husband and father, was this year that I spent as a missionary in Honduras, not only informing my views of our country, but giving me a sense of mission in life at a time when I lacked it. That was a powerful faith experience for me.”

Since then, Kaine also has been outspoken about his faith, sometimes rivaling his counterpart, Governor Mike Pence, in the number of times he invokes it. This has not been without controversy. For example, Kaine has said many times that he is personally pro-life but politically pro-choice—in other words, that he is anti-abortion himself, as a matter of conscience, but believes the government should not coerce that moral view on women.

Oddly, some have called this view a “predicament.” But, in fact, it is what a majority of Americans believe: that they personally may be against abortion, but that it’s not the state’s business to force those views on anyone, especially against women who should make such decisions for themselves. As senator, Kaine maintained a 100 percent rating from NARAL, and spoken many times in favor of protecting Roe v. Wade—though as governor, he backed consent restrictions and a “partial-birth” abortion ban. While some in the pro-choice community are unhappy with this ambivalence, it’s not a predicament for Kaine; it’s an asset.

Indeed, the mirror image of Kaine’s position on abortion is his position on the death penalty: personal moral opposition, but a concurrent belief that the state should not impose a moral view on others. As governor, he allowed executions to proceed as sentenced. “I take an oath to uphold the laws of the commonwealth,” he said in 2008. “My church doesn’t make me cross my fingers when I do.”

Kaine’s Catholicism also represents the demographic future of the Catholic Church, and of America. His parish in Richmond is mostly non-white, and according to one report, Kaine has even sung in the mostly-black gospel choir. Both as a matter of daily reality and ethical commitment, Kaine’s religiosity includes a commitment to racial justice.

More broadly, as we’ve seen with Pope Francis, the social justice teachings of the church are not to be underestimated. Like Pope John Paul II (though not Pope Benedict) before him, Pope Francis has criticized untrammeled capitalism, pushed for swift action on climate change, and personally demonstrated what concern for the marginalized looks like. If any of these views were to be put into practice, the results would look more like Bernie Sanders than Clintonomics.

Now, it remains true that on some issues important to former Bernie-backing progressives, Kaine is a disappointment. He’s basically a free trader, and has often sided with Wall Street in various debates. He has often cozied up to financial elites, accepting a lot of gifts and free vacations. And, yes, he’s a fiftysomething white guy.

But Kaine’s quintessentially Catholic yet stereotype-defying brand of religious liberalism has the potential to disrupt the voting patterns and assumptions that most people have about religious Americans. According to conventional wisdom, religious Christians are supposed to look like Mike Pence: hardline on abortion and homosexuality, but pro-business and anti-social-safety-net when it comes to economic policies.

A lot of Christians, though—especially non-white Christians—look more like Tim Kaine. The American Catholic Church, in particular, is far less white and far less conservative than most people think, with Hispanic Catholics (34 percent of the U.S. Catholic population and growing) regularly polling to the left of non-Hispanics on a wide range of social issues. They don’t get as much press, but they are the future.

“There’s what we are today and there is what we ought to be. I think both religion and politics are both about that,” Kaine said on Charlie Rose in 2008. “We can take the conditions we’re in and say, shoot, that’s just the way it’s going to be. But, boy, every human being I’ve ever met of whatever background, they recognize there’s a gulf between where we are individually, where we are as a people, as a culture, and where we ought to be. Politics and religion are both about… breaking out of our own selfishness and our own limitations and saying what is and isn’t necessary. We can be better than that.”

That is a quintessential progressive religious vision, and it is not something we’ve heard much on the presidential campaign trail this year, or most years, especially from someone who goes to mass every week. Don’t believe the hype that Kaine is the safe, boring choice. He could be a game-changer.