Your correspondent Mr. Nale made a business trip last week to Acton, California, to interview a pig. Your other correspondent is not as young as he used to be and stayed home—missing not only the pig but a goat, two friendly cows, one cow that was not friendly, a lisping turkey called Madeline, and a couple of hundred other animals, give or take, each with a story to tell. Some of them have fallen out of trucks on the highway, some have been mutilated, some abandoned. Terrible stories.

The good news is we promise not to make you listen to 200 of them today.

What we are here about today is retirement.

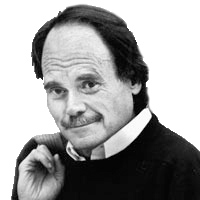

In particular, the retirement of Jon Stewart, who was not long ago the host of a brilliant TV program. Or so says Mr. Nale, who posits Stewart may have offered us the best late-night television ever. As mentioned, your other correspondent isn’t as young as he used to be and Jon Stewart came on after his bedtime.

In any case, retirement. In the animal kingdom, retirement usually means somebody younger comes along and eats you. From what I have seen of the movie business, it’s the same thing. Jon Stewart, though? He is too young—what is he thinking?

Here is a story about retirement. For the last 30 or 40 years of his working life, a man named Larry McMullen wrote a newspaper column for the Philadelphia Daily News. Larry was from South Philadelphia, and the best match of a newspaper columnist to a city I ever saw. He wrote five days a week (and later four and then three), burning it at both ends, you could say—most big papers these days only ask for one a week—and somehow toward the end of all the years, he lost track of how much it meant: how much he meant to the paper, to the city itself, and how much the column meant to him.

Meanwhile, the big squeeze was underway everywhere in the business—papers going under, cutting staff, cutting size, cutting the news hole—and to meet stock-market expectations, papers all over the country were paying employees to quit. Buyouts, aimed in particular at the old timers making the most money.

Without going into his reasons, he allowed himself to be bought out. For something less than a year’s salary and a year or so of health-care insurance, etc., he gave up the best job a newspaperperson can have, with nothing particularly in mind to take its place. But celebrity or not, as soon as you don’t matter as much to the people around you, you don’t matter as much to yourself.

McMullen saw his mistake and tried to un-retire his way back onto Page 2, but for reasons I will never understand the paper wouldn’t deal. Maybe up in the corporate offices they were afraid of setting a precedent. So Larry looked around for some decent-paying freelance writing jobs, but his talent was specific in many ways to Philadelphia, and specific to newspapers, and you probably had to already know something about the place and the people to understand how good his stuff was. And even if that hadn’t been the case, jobs worth doing (financially) were hard to come by, and went to big-time magazine writers on contracts anyway. So Larry looked around for some not-so-worth-doing-financially jobs, and there weren’t any of those around either. All his dead-on insights into the city didn’t mean a thing.

In the end he stumbled on to a local magazine. The way he explained it to me was that a couple of well-heeled Philadelphians had decided it might be exciting to publish a slick-paper magazine, and didn’t have any words to put inside it. They said they wanted Larry’s words—which he found flattering, even if it was not much money. A hundred dollars now and then, when he used to make 15 or 20 times that for the same amount of work.

So Larry wrote for the well-off Philadelphians, and sometimes allowed them to use old columns that had run in the newspaper years earlier. It turned out, though, that the well-off Philadelphians were on a budget, and the new publishers began to hedge on even the little payments—sometimes a hundred dollars, and other times nothing at all.

Nothing, that is, except a promise, and the promise was to publish a collection of McMullen’s columns. The job he’d walked away from at the Daily News was suddenly more important to him than he’d known when he was doing it. He asked me to write a foreword for the collection, which turned out not to be as hard as I’d thought. The way you do that, if anybody ever asks you, is you sit down and write what you wish somebody would write about you.

Before that, though, I warned him it was hard times in the book business, and getting a collection of local columns published by a real publishing house—no matter how good the columns were—was impossible.

Larry believed he had it covered. All the stuff he’d done for little pay and no pay, it was all in exchange for publishing his collection. Larry missed the newspaper work, but at the time we talked about the collection what he missed most was being the guy who did the work. He said he wanted the collection, “So at least my grandchildren will know I was somebody once.” It was a handshake deal, and you probably already see it coming.

I did, and didn’t push the conversation one inch farther. I wrote the foreword. Larry had already gone through thousands of columns—dozens and dozens of hours—and culled his stuff to maybe a hundred pieces, and one of the saddest phone calls I ever got came a month later, when he called to apologize for wasting my time. The well-heeled folk said there had been a misunderstanding. Their understanding was that Larry had been doing all that work for the prestige of appearing in the pages of an empty little magazine nobody ever heard of. And that, as they say, is that, except to mention that McMullen and I shared an office for years, and he was much smarter than this incident makes him sound and he was inside-out honest.

In the end, I made a few calls to publishers, to agents—the only chance he had was with one of the local college presses, but they were in the same mess as the rest of the publishing world, and while I never talked to an editor who didn’t admire the columns, as a practical matter of business, the answer was always no.

So Larry died, but before that happened he at least came around to seeing that he didn’t need a collection of columns to show anybody anything. For 30 or 35 years—the last two-thirds of his working life or so—he was the best newspaper columnist in the fourth-biggest city in America. A 30-year dialogue with the people he knew best and understood. That was who Larry McMullen was and what he did. His only problem was he quit while he could still do the work, and he was good enough at it that nothing else he could do afterward had a chance of meeting that high standard.

Which is the long way around, I know, of getting back to Jon Stewart and your younger correspondent’s business trip to Acton, where Farm Sanctuary Animal Acres sits on a plot of desert, one of four such retreats in the country. This is the work Stewart and his wife, Tracy, mean to do now that he’s through with regular television.

Admittedly it’s a strange fit, the television star and broken animals, but it also makes a kind of sense:

Jimmy the pig, turned over to the shelter by a homeless man who said he couldn’t take care of him anymore.

A cow named Bruno who fell off a truck on I-14 near Palmdale, just about ruining his legs; his companion Paolo, who bears foot-long scars from a coyote attack and whose previous owner had closed the wounds with duct tape.

Maria, who escaped from a goat farm where, as a milking goat, she was kept barefoot and pregnant, and as a matter of business, her newborns were slaughtered as they came out. Goats, it turns out, are attached to their offspring, and mourn their deaths as deeply as humans.

The place is run, in the words of your correspondent, “by a steer with large horns and balls halfway to the ground.” Also by a woman called Breezy, who smiles when the correspondent suggests making friends with what we, back in the home office, are going to say is a bull. Everything else out here is friendly, observes your correspondent, but now that he thinks it over, something in the way the animal watches tells him not to make friends. The cow’s name is Mr. Ed, and he does in fact watch until Mr. Nale is back in his truck and headed up the road.

For a sweeter ending, we visit Madeline, once a factory turkey. She lisps, but then factory turkeys are always “clipped,” meaning the tips of their beaks and sometimes their toes are cut off, to prevent fights.

Yes, you might be thinking, she’s only a turkey, but Madeline’s pawing the ground, can’t wait to visit.

Breezy sits down on the dirt floor of the pen, and the turkey climbs into her lap. It comes to your reporter that Jon Stewart would also look comfortable with a turkey in his lap. One of her wings comes up and around, and if she is not hugging the woman, it is something very close, pushing up into her chest, making excited noises that you probably don’t know can come out of a turkey and then she quiets and settles into a kind of rapture, and she purrs.

So maybe Jon Stewart knows what he’s doing.

Maybe the key to retirement is as simple as a better class of pig.