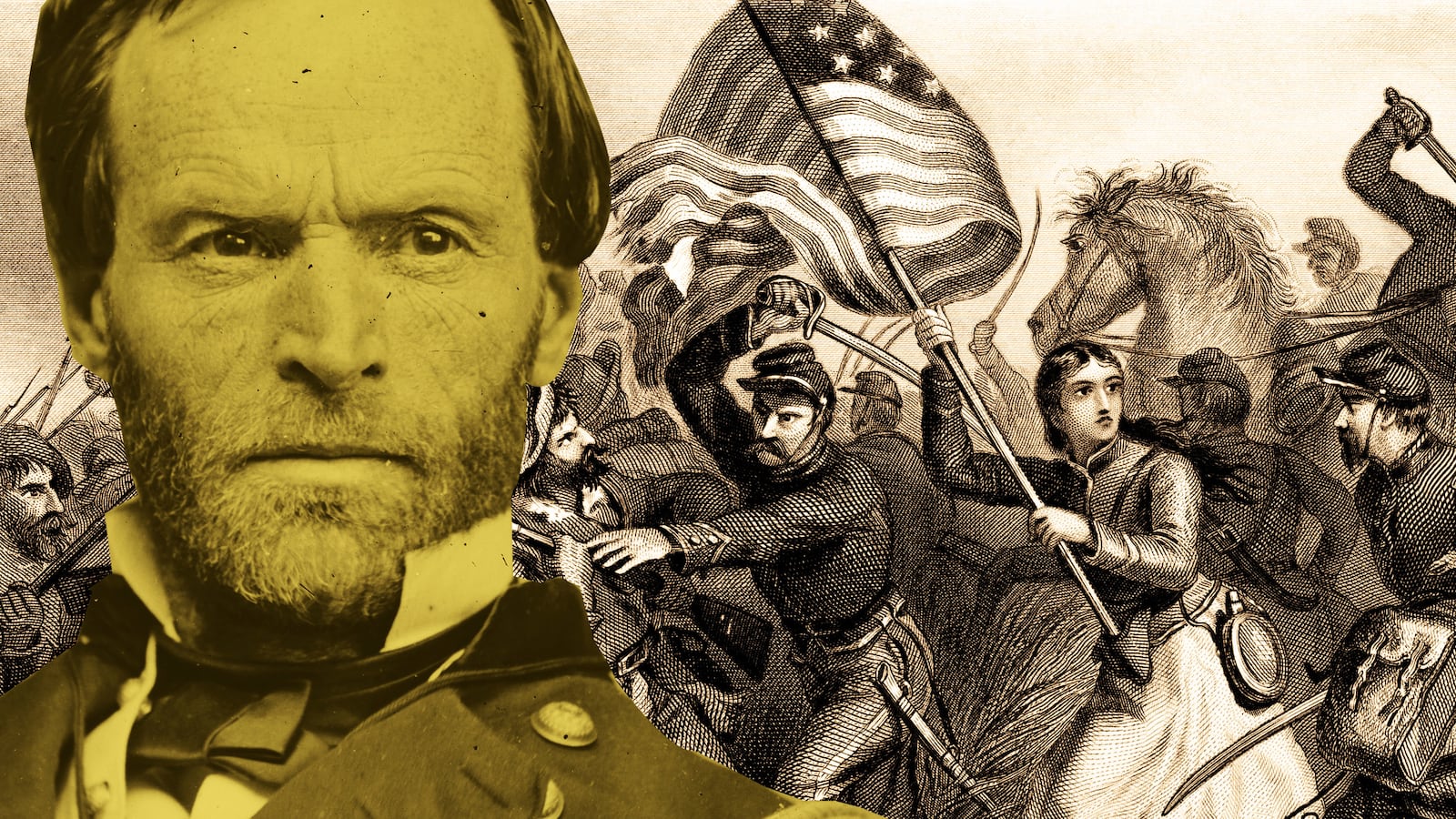

“I am going into the very bowels of the Confederacy,” wrote William Tecumseh Sherman early in 1864 to his superiors in the Union command, “and will leave a trail that will be recognized fifty years hence.” It seemed at the time a rather over-the-top pronouncement from the Civil War’s most quotable and strategically sophisticated general.

Yet in hindsight, it’s clear that “Uncle Billy” had understated the impact of his deep incision into the enemy’s heartland. Even today, the trail of terror and destruction wrought by his army in Georgia and the Carolinas remains indelibly fixed in the collective consciousness of the American South. And the strategic rationale behind Sherman’s famous march continues to be a subject of intense study and controversy among historians, as a torrent of biographies over the last thirty or so years attests.

For the first two years of the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln and the Union command made a sharp distinction between their army’s treatment of Confederate combatants and Southern civilians. The former were to be attacked with the utmost violence, and if necessary, annihilated; the latter treated with restraint and respect. As the war ground on into its third year with casualties mounting at a ghastly rate and no Union victory on the horizon, it was Sherman—not Ulysses S. Grant or Lincoln—who most forcefully called into question the viability of that policy, and put forward a devastatingly effective alternative.

It was no longer sufficient to wage war against Confederate troops, Sherman explained to General Henry Halleck, chief of staff of the Union Army in fall of 1863. If the Union was to prevail, the Southern civilians who supported the war effort had to be made to suffer, too. As Sherman famously wrote to Gen. Halleck, “all in the South are enemies of all in the North… We are not only fighting hostile armies, but a hostile people, and must make [them] feel the hard hand of war.”

Lincoln and Grant, Sherman’s commander and confidante, were initially skeptical, but before too long the loquacious, intense general from Lancaster, Ohio, who had spent much of his military career in the South and knew its people well, brought both men around to his way of thinking. The Union’s innovative strategy of 1864-65 aimed to break the will of the Southern people to carry on the fight, and lay waste to the Confederacy’s infrastructure and war economy at the same time.

Sherman set the stage for his campaign of psychological and economic warfare with a brilliant display of maneuver warfare: the drive on Atlanta, a crucial logistical hub that became a symbol of Southern resolve as Sherman’s army of 100,000 began its drive on the city from Chattanooga, about 120 miles northwest, in May 1864. The fall of Atlanta, said Confederate President Jefferson Davis, would “open the way for the Federal Army to the Gulf [of Mexico] on the one hand, and to Charleston on the other, and close up those rich granaries from which Lee’s armies are supplied. It would give control of our network of railways and thus paralyze our efforts.”

The topography between Chattanooga and Atlanta is dominated by steep mountains, ridgelines and three wide, churning rivers—excellent defensive ground. Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston, perhaps the South’s best defensive general, established a formidable network of fortifications on Rocky Face Ridge in northwest Georgia, astride the railway Sherman would need to hold to provision his army during the campaign.

In early May, Sherman feinted toward the main Confederate positions, and then sent 25,000 troops in a flanking maneuver around Johnston’s left, threatening to envelop his entire army. Johnston slipped the noose just in time, tore up the railway, and promptly retreated 15 miles south. There, at Resaca, he frantically set up another set of fortifications, determined to blunt the Union advance. Sherman again refused direct engagement. The Federals brilliantly executed a second turning movement, crossed the Etowah River, and forced Johnston into another hurried retreat. In three weeks, Johnston had been maneuvered out of two major defensive positions, and forced to retreat 50 miles without inflicting significant damage on Federal forces.

Sherman’s engineers quickly repaired the railway. Supplies were brought up, and then, Sherman went around Johnston’s army yet again, this time snaking around the Confederate left flank at Allatoona Pass in three columns. Not until the end of June was Johnston’s reinforced army able to halt Sherman’s drive at the Battle of Kennesaw Mountain. There he inflicted heavy casualties on the Yankees, but nowhere near heavy enough to relieve the pressure on Atlanta, which lay only 22 miles to the southeast.

Heavy rains came to Georgia. There was a lull in the fighting. Much to the consternation of Jefferson Davis and the Confederate high command, Johnston couldn’t find the nerve to launch a major attack on the invaders. He was relieved of command on July 17, and replaced by John Bell Hood, perhaps the South’s most aggressive general officer. Robert E. Lee described Hood as “All lion, none of the fox.” True to form, the Lion launched several reckless attacks against superior Union forces, and took a terrible pasting for his troubles.

Sherman closed in ever tighter, taking Atlanta under siege early in August. Later that month, he sent a large force well south of Hood’s army, and cut the last railroad line into the city. Hood’s defense became untenable. He withdrew to the north, hoping to lure the entire Federal army after him.

Sherman wasn’t biting. He detached a 50,000-man force under George Thomas to destroy Hood’s army. Thomas, “the rock of Chickamauga,” crushed Hood definitively at the Battle of Nashville in mid-December. Meanwhile, Atlanta belonged to the Union and Sherman, and its railway yards and factories and everything else of military value was destroyed or confiscated.

The seizure of Atlanta had profound political as well as military ramifications. “The disaster at Atlanta,” the Richmond Examiner reported, “saved the party of Lincoln from irretrievable ruin.” And so it did. Lincoln, who had been trailing peace candidate George McClellan in the polls all summer, was re-elected in November by a wide margin.

Just a week after the election, Sherman’s high-spirited army of 60,000, hardened by months of combat, began its 285-mile march from Atlanta to Savannah, and the sea. Loosed from its own supply lines, the army would forage for supplies off the countryside. “We cannot change the hearts of those people of the South,” Sherman explained to Grant, “but we can make war so terrible… [and] make them so sick of war that generations will pass away before they would again appeal to it.” Major Henry Hitchcock, an Alabaman on Sherman’s staff, fleshed out his commander’s rationale for the operation nicely when he wrote that if the “terror, grief and even want” the army was about to inflict on the people of Georgia “shall help paralyze their husbands and fathers who are fighting us … it is mercy in the end.”

Having obtained a detailed map of Georgia from the Department of the Interior and a copy of the 1860 census, Sherman and his officers charted a route of march that took them through some of the most agriculturally rich counties in all of Georgia. They were able to pinpoint the most promising targets along the route with ease, and earmark them for foraging or destruction.

The army moved at a torrid pace in four columns —as much as 10 miles a day—tearing up railroad tracks, ransacking towns, burning down granaries, mills, factories, and large plantations, but leaving private homes or ordinary citizens undisturbed for the most part. But wrecked bridges, roads, and guerrilla attacks were to be considered signs of “local hostility,” and commanders, wrote Sherman, should “enforce devastation more or less relentless according to the measure of such hostility.”

A division of Union cavalry under Gen. Judson Kilpatrick screened and scouted for the infantry columns, exhibiting a special flair for wanton destruction of property, both public and private. Teams of foragers—“Sherman’s bummers,” as they were called—confiscated whatever the army needed to keep rolling, and then some: horses, wagons, potatoes, chickens, hogs and cattle. They cut a swath of terror and destruction between 25 and 60 miles wide through the Georgia countryside.

And they freed slaves—more than 25,000 were liberated on the march. Many joined the Army’s pioneer battalions as laborers to help rebuild roads and bridges Confederate forces had destroyed as they fled in the wake of the Union juggernaut.

Six days out of Atlanta, the adversaries fought the deadliest set-piece battle of the entire march. Around the town of Griswoldville, three brigades of Georgia militia attacked a substantial force of Union troops, including a cavalry unit equipped with deadly Spencer repeating rifles. More than 500 militia men were killed or wounded, and 600 captured. Most were old men or teenagers. For most of what remained of the march, understrength Confederate forces were reduced to harassing the Union advance with small arms fire before retreating in haste.

Just before Christmas, Sherman’s columns marched into Savannah unopposed, seizing 150 artillery pieces, 250,000 bales of cotton, and a first-class port the Confederacy could ill afford to lose.

The march to the sea was complete—and a resounding success it was. Grant called on Sherman to embark his army by ship as soon as possible for Virginia to reinforce his own forces, then locked in horrific combat with Lee’s army in Virginia. Sherman had a different idea. A restless soldier of enormous energy and drive, he had an almost mystical commitment to breaking the will of the people of the South and reforming the Union, and he had succeeded in transmitting that commitment to his soldiers. He wanted to take “hard war” to the Carolinas, particularly South Carolina, the cradle of the Confederacy, where support for the cause remained more ardent than anywhere else in the South.

The Palmetto State’s spirit of defiance had to be utterly broken before the war could be brought to an end. “The truth is, the whole army is burning with an insatiable desire to wreak vengeance upon South Carolina,” said Sherman before embarking. “I almost tremble at her fate.”

His ultimate destination was Goldsboro, North Carolina, where the army, in historian Michael Fellman’s memorable phrase, would become “the second jaw of an enormous Union vise,” poised to close in on Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia from the rear, while Grant’s force attacked en masse from the north. (Lee’s much-depleted army collapsed so quickly in early April that the pincer attack proved unnecessary in the end.)

Grant wisely consented. Already Sherman’s operations in Georgia had had a devastating impact on morale throughout the South. Desertion rates in Lee’s army had spiked precipitously.

On February 1, Sherman’s force of 60,000 troops began its 400-mile drive through the Carolinas. The Confederate high command scrambled to deploy 10,000-man garrisons at Augusta to defend a critical munitions plant, and another 10,000 at Charleston—the two most alluring targets within range of the Union army pressing north from Savannah. Sherman made feints in the direction of both places, but struck at neither one. Instead, he destroyed the railway between those cities, laid waste to several towns, and a majority of the private homes along the line of march.

And indeed, the scale of destruction in South Carolina was far, far greater than it had been in Georgia—or than it proved to be in North Carolina, where the people were generally resigned to defeat before Sherman and his bummers arrived. Confederate cavalry set bales of cotton ablaze to slow Sherman’s advance through Columbia, the state capital, but the move backfired: rampaging Union troops, their spirits fueled by vast stores of liquor, burned most of the city to the ground—against Sherman’s orders.

The psychological impact of the march through South Carolina was all the more devastating because Confederate engineers had assured the high command that it was impossible for any army to cross the state’s vast, swampy lowlands in winter. Sherman’s pioneer battalions thought differently. They built mile after mile of corduroy roads to cross the swamps, and rebuilt bridges destroyed by enemy forces with astonishing speed. A month into the march, a South Carolinian wrote in his diary, “All is gloom, despondency, and inactivity. Our army is demoralized and the people panic stricken … The power to do has left us … to fight longer seems madness.”

In 45 days, Sherman’s army crossed nine major rivers and marched more than 400 miles in all. And he tore the heart out of the people of South Carolina along the way.

In seeing the Civil War as a struggle between peoples and economies, as well as armies, William Tecumseh Sherman has been described as among the first truly modern generals. Certainly he had a remarkably sophisticated understanding of the interplay between conventional military operations, politics, and psychology. But contrary to popular belief, Sherman was not a practitioner of “total war.”

If that term means anything, it means targeting the civilian population for indiscriminate destruction, with a view to achieving unconditional surrender. The Americans, British, and Germans all practiced total war when they combined strategic bombing campaigns against enemy cities with conventional military operations on land and sea.

Sherman, in fact, was a practitioner of “hard war,” which sought some of the same ends of total war—breaking the will of the civilian population and destruction of the war-making capacity of the enemy—by less draconian means than true total warriors would employ. No one knows how many Southerners were killed by Sherman’s army as it ripped out the innards of Georgia and the Carolinas, but contemporary historians all agree that it was not very many.

Ironically, Sherman has been reviled by generations of Southerners—and no small number of historians—for practicing a kind of war that eschewed conventional combat, and the conventional fighting in the Civil War was enormously destructive of human life. Until the end of his life in 1891, William Tecumseh Sherman remained unapologetic for his final campaigns of the Civil War. He had done what he had to do to bring the war to a close as soon as possible, and save the Union. That was what mattered to Uncle Billy above all else, and his contribution to that accomplishment was enormous. “If the people raise a howl against my barbarity and cruelty,” wrote Sherman, “I will answer that war is war, and not popularity seeking.”