MOSCOW — Tatars knew Remzi Memetov as a jovial cook who made the best traditional plov, a dish of rice and lamb, in the little Crimean town of Bakhchysarai. Memetov’s cooking was especially popular among Muslims coming to the local mosque to participate in religious festivals.

Nobody in the town’s sizeable Tatar community would have imagined that their favorite chef would be accused of terrorism.

At 6 a.m. the morning of May 12, the Memetov family heard a knock at the door of their house on Lazurnaya Avenue. The voice outside said: ”Open up, this is the Federal Security Service.”

The visitors were two FSB investigators, two official witnesses, who the FSB invited to be present while they searched the house, a camerawoman, and several people who did not identify themselves.

After a few questions, they looked through all the rooms in the house, confiscating a few religious books and a few CDs. As the investigators were taking Remzi Memetov away, his neighbors gathered around the FSB officers to ask why they were arresting a friendly cook everybody loved. An official said Memetov would just be away a few minutes, just enough to sign a few papers.

“Shame, Shame!” people chanted. And soon their worst expectations came: Memetov’s wife and two adult sons learned he was accused of participating in terrorist activities as a part the Islamic movement Hizb ut-Tahrir, which is banned in Russia. He was accused together with three more neighbors, who were arrested the same day. One of them, Enver Mammoth, had seven little children.

Soon after Moscow annexed what had been Ukrainian Crimea in 2014, Russian security agencies began to crack down on Muslims there, and after many arrests they knew only too well what happened when the FSB detained one of them.

The Daily Beast interviewed several Tatar families whose loved ones disappeared last year. The Tatars complained that detentions, abductions, false accusations, and torture became a part of Crimea’s daily life.

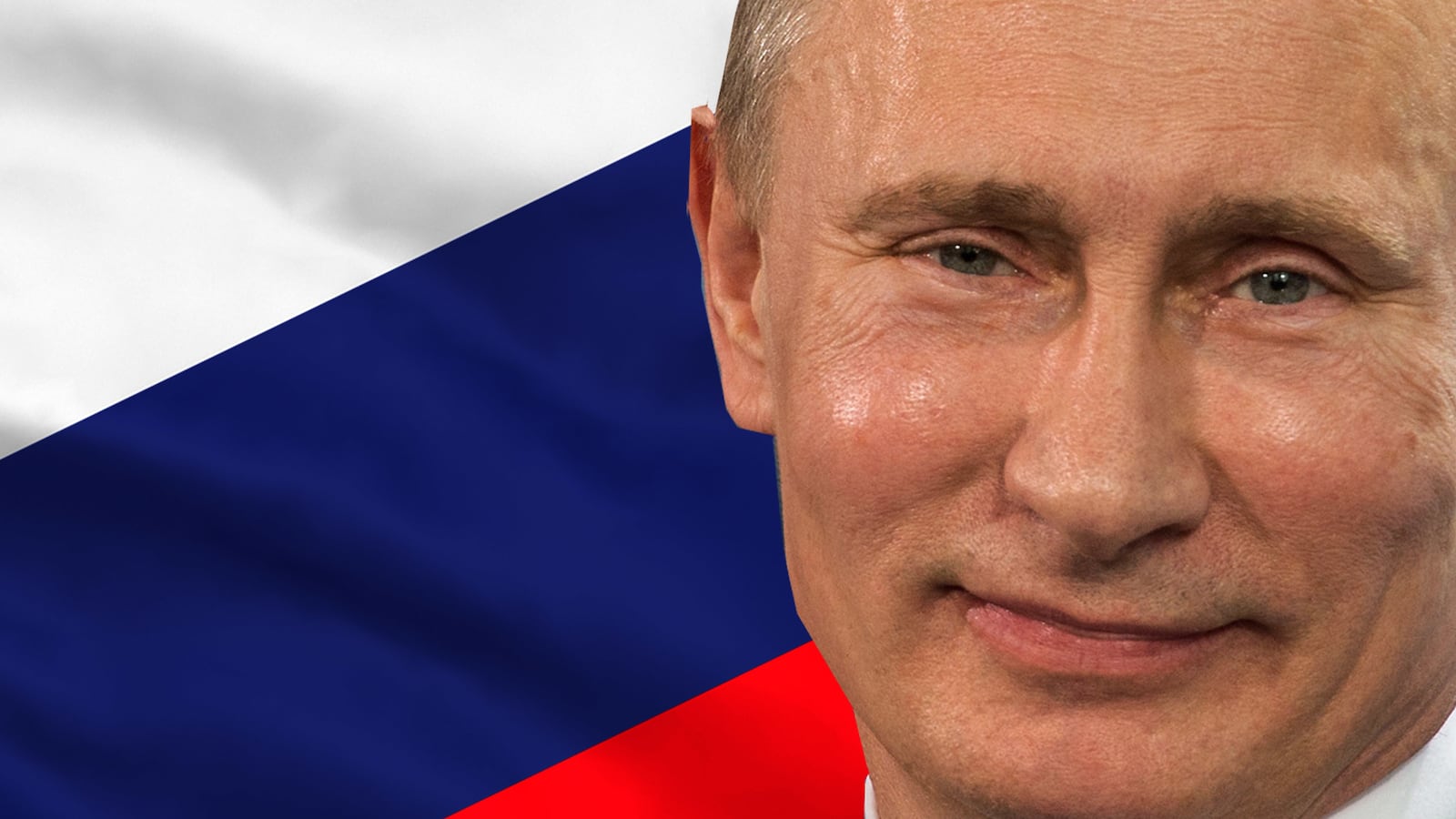

And today, prosecutions of alleged Hizb ut-Tahrir Muslims in Crimea are just one part of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s big new war on terror launched in the Ural regions, in Siberia, in annexed Crimea, and in central Russia.

In a country of conspiracies and major unsolved crimes, in which security services operate without the oversight of politicians or civil society, no one can be sure of the true nature of “terrorist” plots and incidents. What is unclear in Putin’s present war on terror is how many threats are real and how many expedient.

“Sometimes security services persecute people when it is convenient,” Alexander Cherkasov, chairman of Memorial, a group of human-rights defenders, said in recent interview. “[We] reported on thousands of cases involving abduction or killings of Muslims in the Northern Caucasus—and sometimes there is a real threat of terrorism. We need to be careful looking into each case,” he told The Daily Beast.

On Wednesday, Russians woke up to the news of a terror threat and the sound of explosions in the center of Saint Petersburg. Up to 20 security service vehicles surrounded an apartment building on Leninsky Prospect. At 11:20 a.m., residents heard two blasts, saw smoke pouring from a window and men in gas masks emerging onto the balcony of one of the apartments.

Russian authorities reported that four Islamic militants were killed in that special operation. According to the RIA.ru news agency, the security services in the Kabardino-Balkaria republic asked the FSB to detain a group of alleged militants from the North Caucasus who had made their way to Saint Petersburg. The FSB report said that as a result of the operation, in addition to those killed, three militants were detained. On Thursday RIA.ru reported that the antiterrorism agency in Kabardino-Balkaria refused to give any comments about Wednesday’s special operation.

The methods used by the FSB in the North Caucasus and have been a matter of concern for human-rights defenders for years: “Members of the security forces and law enforcement bodies still resort to illegal means such as abductions and secret detentions, extrajudicial killings and torture, and they continue to enjoy almost complete impunity,” a draft resolution by European Council declared in April.

Now the Kremlin’s leader is talking of new terror threats coming from Ukraine. Last week, Putin sat down with his top military commanders and intelligence officers from the Security Council and accused Ukraine of plotting terrorist attacks and killing two Russian officers in Crimea the previous day. Russia was not going to forgive Ukraine for that, Putin said, and declared he would strengthen Crimea, conduct war games, and review the “scenarios for counter terrorism security measures” not only along the land border, but also offshore and in the air.

Meanwhile in Western Siberia, the Russian Federal Security Service discovered “an international network of terrorism propaganda.” Last week, the same day as the Security Council meeting, the FSB searched at least 26 apartments and detained as many as 96 people in the Tyumen, Sverdlovsk, and Cheliabinsk regions.

“See, the FSB have to demonstrate that they can work well and find terrorists,” says Igor Bunin of the Center for Political Technologies, a Moscow-based think tank. “I expect that the majority of the detainees were Salafis but did not recruit for ISIS.”

But, then again, as Katia Sokirianskaia, a Turkey-based researcher at the International Crisis Group, tells The Daily Beast, “In the last several years, as some Russian Muslims radicalized, there were cases of jihadists also leaving for Syria from Siberia, including those from the local Muslim community and Muslims who had come to Siberia to work.”

It looks like terrorists are everywhere, both inside and outside Russia’s borders. But the accusations about Ukraine remain the most problematic at many different levels.

Putin now refers to Ukraine as a country practicing “terror”—a state sponsor, as it were—and is no longer dealing with its leadership. The Kremlin’s hopes to solve the Ukrainian issue and see some of the economic sanctions against Russia canceled by the end of this year seem to have fallen by the wayside as Putin said he saw no sense in negotiating peace with terrorist Ukraine.

Many analysts see behind this ploy a thinly veiled threat of war, and there is an oft-cited historical precedent.

Back in May 2008 the Kremlin also decided to stop communicating with then-Georgian President Mikheil Saakashvili, and by August there was a war between Russia and Ukraine, with Russian tanks rolling inside the Georgian border toward Tbilisi before a ceasefire was agreed on.

This time it is hard to find anybody in Moscow who believes the Kremlin is ready for a bigger conflict in Ukraine, which could trigger World War III. And for all Putin’s bravado, there are signs the top leadership is shaky. Putin seems to have lost faith in his senior team. Last Friday morning he sacked the head of his administration, his longtime ally and fellow KGB/FSB veteran Sergey Ivanov.

“Ivanov symbolized Putin’s old team, who clearly had no strategy and reacted by inertia,” Yuri Krupnov, a pro-Kremlin political analyst, told The Daily Beast.

Putin loves to embrace the language of the West and then use it against Western policies. Thus in Syria, while attacking Western-backed opponents of the Assad regime, he claims he is fighting terrorists. Now he says Russia is threatened by terror and will fight it just the way the West does—but in Russia’s case it’s coming from Ukraine.

“War on terrorism is the new trend,” said Cherkasov. “It sounds serious to both the West and to many in Russia.”

In the last two years, over a dozen Ukrainians were accused of organizing or assisting terrorist attacks. At least four of them are on trial in Rostov-on-Don, a town in southern Russia near Ukraine.

Putin’s FSB detained seven suspects for involvement in the alleged “terrorist attack” on the Crimean peninsula that, according to the FSB, took place on Aug. 7. Both Kiev and Moscow started war games close to the Black Sea. Russia acknowledged it deployed S-400 anti-missile systems to Crimea and strengthened its defense of the peninsula.

“I believe that the FSB put a lot of pressure on Putin after this attack in Crimea; but he would hate to have a real war with Ukraine now, as the Russian economy is going down the drain,” said Bunin.

Meanwhile, Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko alerted his forces to get ready to fight with the Russian army at any moment.

In the last few months the FSB war on terror concerned many Muslims in North Caucasus and in the Ural regions. Last month five Muslims were punished with prison terms in Bashkortostan, a republic in the Ural mountains. But it’s the Muslims in Crimea, mostly Tatars, who are the real focus of hostility: Earlier this year 14 Crimea Muslims were accused of ”organizing terrorist activities.”

And that jovial cook, Remzi Memetov? He admitted, very likely under duress, that he had been a part of Hizb ut-Tahrir. The Crimean court decided to keep him under arrest until his next hearing in October.

“First they extended the ‘15 minutes’ by two months, then they probably realized they had no evidence against him but kept him behind bars for a couple months more,” Memetov’s oldest son, Deliaver Memetov, told The Daily Beast in a phone interview, “and if the court finds him guilty, he will spend more than 10 years in prison.”

The series of arrests reminded Crimean Muslims of the 1944 deportations, when Soviet leader Joseph Stalin accused the community of collaborating with the Nazi occupiers and ordered more than 100,000 Tatars put onto cattle trains, moving them out of their historical settlement on the Black Sea peninsula to Central Asia.

This year the FSB investigated more than 2,000 cases related to terrorist activity. “This conveyor belt of terrorism seems to target Tatars in three different regions of Crimea to push the community off the peninsula,” Anton Naumlyuk, a Radio Free Europe investigative journalist, told The Daily Beast.

This year Naumlyuk followed over a dozen cases of new Russian “terrorists.” “As a result of FSB arrests,” he said, “Crimean Muslims became a much more united community.”

The Tatars agreed. “None of us is going to leave Crimea again, our community has been pushed around enough,” Deliaver Memetov told The Daily Beast.

When it comes to fighting a real war against Ukraine, Russians seem to be united, too. They don’t want it. Even the alleged threats of terror could not convince them, or at least not those who listen to Echo of Moscow, that war would be a good idea: The social polls the radio station ran last last week showed that 82 percent of Russians were against a Russian army offensive operations in Ukraine.

So the army most likely will not deploy, but the FSB will be more active than ever.