Long before the phrase “check your privilege” became a progressive meme and a BuzzFeed quiz (“How Privileged Are You?”), Peggy McIntosh, a woman’s studies scholar at Wellesley College, wrote a totemic paper on privilege theory. In 1988, she articulated 46 examples of white privilege, like “I can be pretty sure that if I ask to talk to the ‘person in charge,’ I will be facing a person of my race.”

Current debates about privilege in education, particularly on college campuses, are playing out in student op-eds, new diversity initiatives, and “Examining White Identity Retreats.”

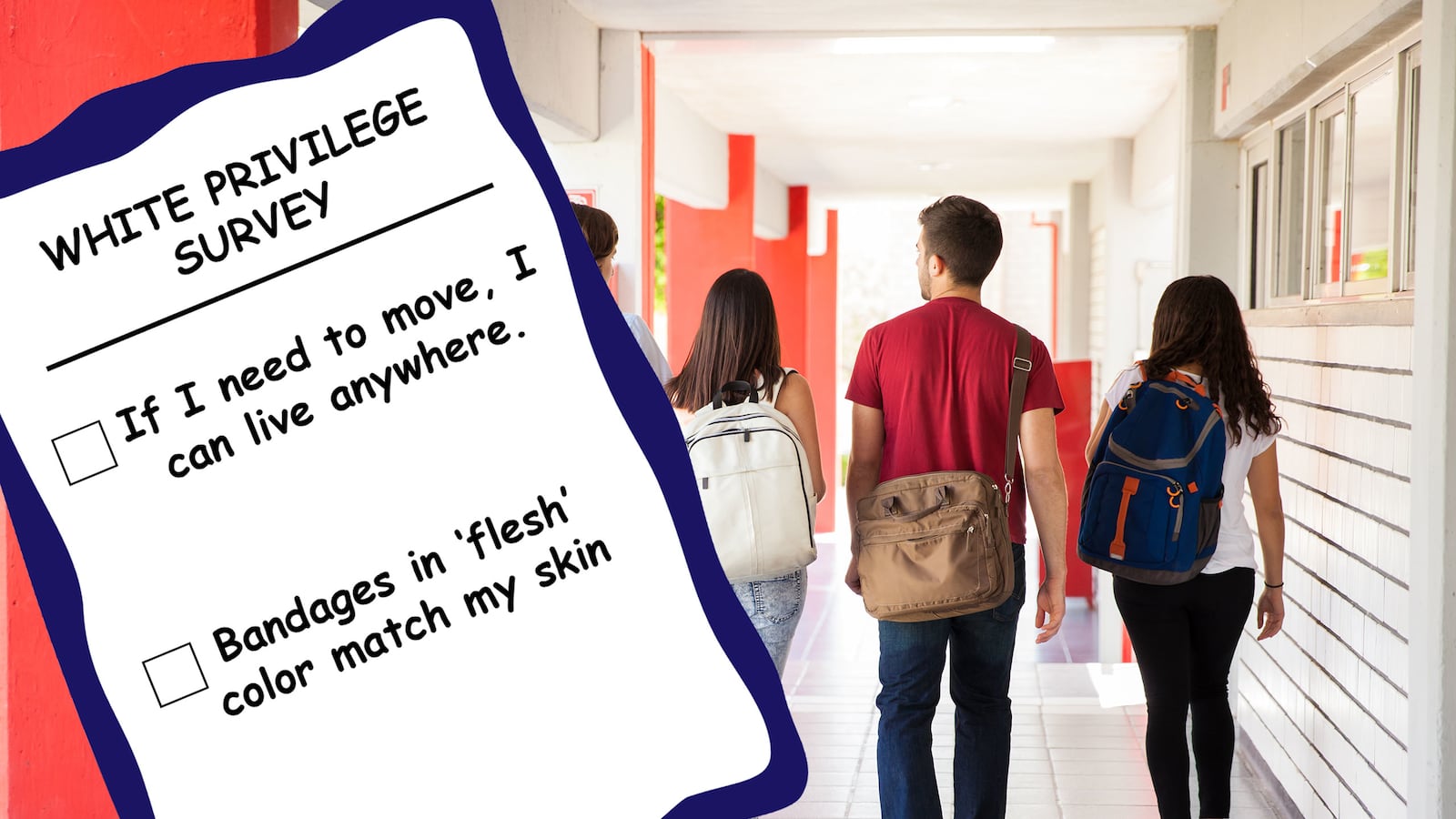

In recent weeks, a White Privilege Survey adapted from McIntosh’s paper has caused controversy at schools in Colorado and Oregon, with some staff members and parents suggesting the poll pushed a political agenda that doesn’t belong in an educational setting.

On Wednesday, an anonymous employee at one of dozens of elementary, middle, and high schools in Colorado’s Cherry Creek School District, near Aurora, sent the White Privilege Survey to a local news affiliate and said he didn’t feel comfortable taking it. The survey was given out to staff, rather than students.

The survey slashes McIntosh’s 46 statements about white privilege down to 26 statements, including: “I can be in the company of people of my race most of the time,” “If I should need to move, I can be pretty sure of hassle-free renting or purchasing in an area in which I would want to live,” “I can choose… bandages in ‘flesh’ color and have them more or less match the color of my skin.” and “I can criticize our government and talk about how much I fear its policies and behavior without being seen as a racial outsider.”

Participants give themselves a score of zero (seldom or never), three (sometimes), or five (often true) based on how much each question rings true for them.

“The way this survey is read, it almost wants to like, ‘Shame you for being white,’” one parent at Aloha High School in Portland, Oregon, which had asked seniors to fill out the survey, told The Oregonian in late September, dismissing it as an inappropriate social experiment.

Another parent disagreed: “It’s a huge topic, and it needs to start somewhere,” she said of white privilege. “We are first of all judged by the color of our skin.”

Colorado’s Cherry Creek School District defended the survey in a statement to The Daily Beast, saying that some schools in the district began incorporating a version of McIntosh’s paper created by the Pacific Education Group in 2003, when the district began doing staff diversity training.

“Yes, the survey does make some people uncomfortable. It’s designed to,” the statement reads. Given only to staff, it’s “designed to spur conversations about how the experiences of children and people of color are different than that of most white people.”

Schools in the district do not collect tests, and only participants can see their answers. They’re told to expect and accept that the questions the survey raises may not be resolved.

“If we had all the answers, we would have no opportunity gap,” said Tustin Amole, director of communications for Cherry Creek School District.

When she first took the survey in 2013, Amole said she “wasn’t offended by it but I found it very enlightening because these were questions I had never considered, and they were important.”

She stressed that the survey has been used “consistently” somewhere in the district’s 61 schools since 2003, and that it is a successful component of their staff diversity-training program.

“The work works,” she said, noting that the district’s graduation rate is 80 percent and higher for all ethnic groups, and that the district has seen progress in narrowing the opportunity gap over the last 13 years.

“Our schools are doing better than their inner-city counterparts,” Amole said.

Efforts to educate students about white privilege and valuing differences, whether through surveys or segregated retreats, aren’t new.

Some 30 years after McIntosh published her paper, it’s still fairly obvious that white people have advantages in society that people of color don’t. But the primacy of identity politics on college campuses and in progressive culture in recent years has reinvigorated “white privilege” discourse and, inevitably, provoked the kind of backlash seen from staffers and parents at Colorado and Oregon schools.

In a 2014 interview with The New Yorker, McIntosh said that students at colleges and universities are less likely to react negatively to privilege theory.

“[Colleges and universities] are where you learn to see both individually and systemically,” she said. “In order to understand the way privilege works, you have to be able to see patterns and systems in social life, but you also have to care about individual experiences. I think one’s own individual experience is sacred. Testifying to it is very important—but so is seeing that it is set within a framework outside of one’s personal experience that is much bigger, and has repetitive statistical patterns in it.”