Farting, breaking wind, cutting the cheese, or gas. The English language has numerous words for flatulence and this is even before we devolve into the subcategories that make up the genre. Whatever you call it, farting is a taboo act, but it is also a source of fascination. It’s not for nothing that there is a popular children’s book series called Fart Squad or that the preview of the most recent installment of the Alvin and the Chipmunks dynasty led with the punchline, “Sorry, pizza toots.” Today farting is something for which we perfunctorily ask forgiveness, but in the past it has been the subject of legislation, the cause of wars, and even theologized. We might think of farts as trapped gas, but the history of farting is more than just hot air.

Somewhat counter-intuitively, farting has a spiritual side. Manichaeism, a dualistic religion popular in late antiquity that at one time counted St. Augustine among its members, actually held that farts were the act of freeing divine “light” from the body. Manichaeism may have been, as scholar Robin Lane Fox has noted, “the only world religion to have believed in the redemptive power of farts,” but they weren’t the only ancient group to give the phenomenon a great deal of thought. In addition to laying the foundations of trigonometry, the philosopher Pythagoras was concerned that a person might fart out his or her soul. As classicist Andrew Fenton wryly observed, this can explain why they steered clear of beans. Given that the soul (pneuma) was breath and a fart a kind of breath, the explanation makes a lot of sense.

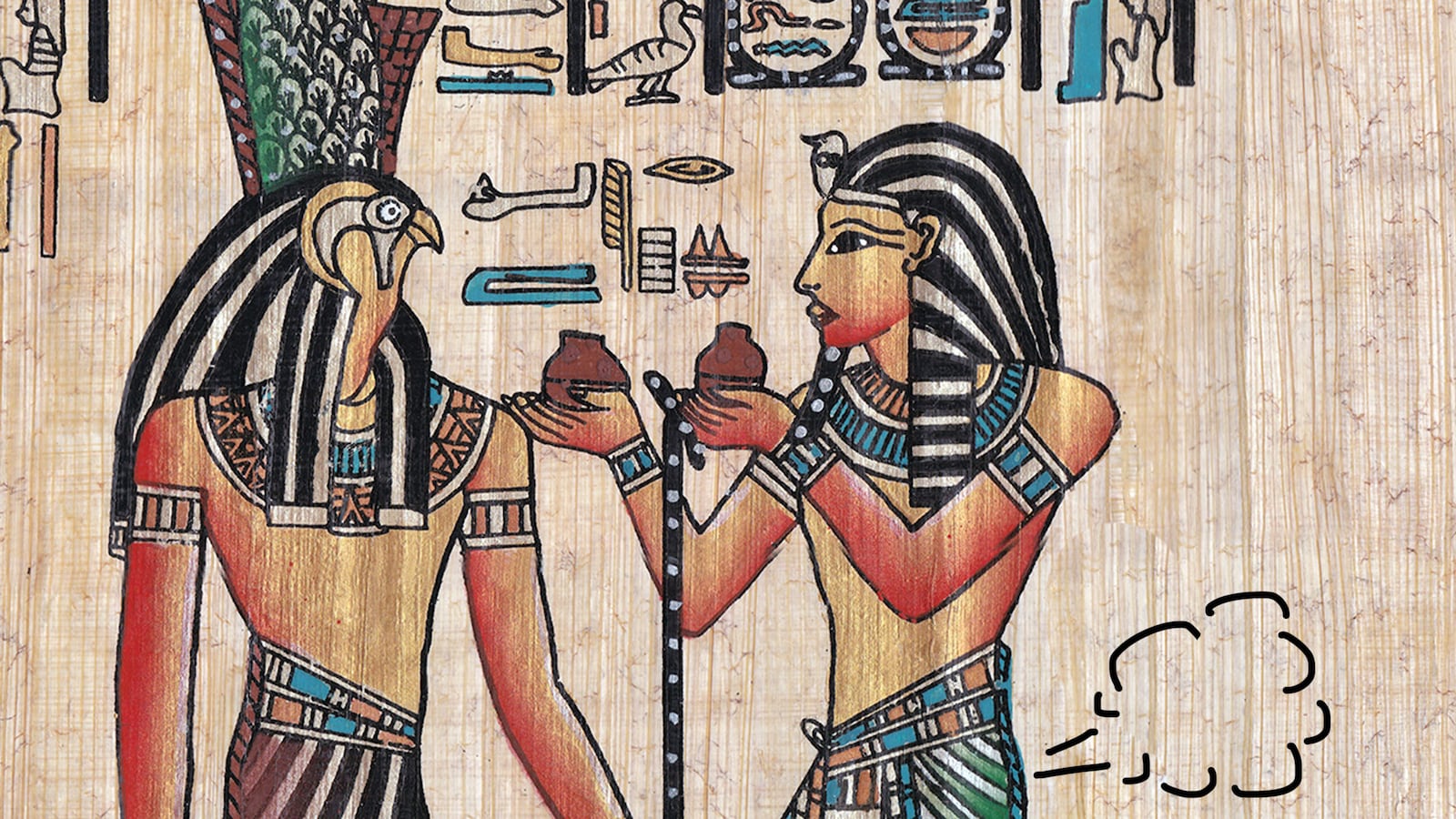

The ancient fear of farting is justified when we consider the surprising number of the stories—that is, more than none—about wars provoked by farts. According to the Greek historian Herodotus, a fart set off a chain of events that led to a revolt against King Apries of Egypt. The repercussions were even worse in first-century Jerusalem: The historian Josephus tells us that an irreverent Roman soldier lowered his pants, bent over, and “spoke such words as you might expect upon such a posture.” The incident took place shortly before the Passover and caused a riot that led to the deaths of 10,000 people.

But it’s not all downside, Dr. Jessica Baron, a historian of science at the University of Notre Dame, told me that some doctors connected farting to sex, “In fact [the second-century physician] Galen sometimes refers to flatulent, or ‘windy’ foods as aphrodisiacs, as do much later Galenists. Hugo Fridaevallis, a Flemish Galenist physician writing in 1569, describes how the production of gas aids in erection, and recommends wind-producing foods (asparagus, in this case) to apprehensive newlyweds.”

For most Christians, farting has often held a more somber significance. St. Augustine offhandedly refers to people who could produce odorless “musical sounds” like “singing” from their behinds, but he seems to have been in the minority. As Professor Valerie Allen has noted in her book On Farting: Language and Laughter in the Middle Ages, most medieval theologians saw farting as “the product of decomposition” and, thus, “as the mark of death.”

Interestingly, farting has been humorous for longer than it has been spiritualized. Arguably the oldest joke in the world is a fart joke. A Sumerian proverb dated to about 1900 BCE reads, “Something which has never occurred since time immemorial; a young woman did not fart in her husband’s lap.” The same theme resurfaces in the writings of the Greek playwright Aristophanes, as well as in Shakespeare, Chaucer, Mark Twain, and One Thousand and One Nights.

In many cases fart jokes have been deemed too scandalous for public consumption. The stories that hinged on farting in One Thousand and One Nights were expunged from all 19th century English translations except that of Richard Burton. Mark Twain’s Elizabethan-period 1601 was first published anonymously, in part because of the farting. And, in 2014, Columbia Pictures pictures delayed the release of the film The Interview, allegedly because of its portrayal of the North Korean dictator Kim Jong-il “sharting.”

Arguably the most successful comedic purveyor of fart jokes, however, was Roland le Sarcere, also known as Roland the Farter, court minstrel to King Henry II of England. Roland performed a dance that ended with the simultaneous execution of one jump, one whistle, and one fart. For his talents Roland was gifted a manor house in Suffolk and 100 acres of land. Roland was so beloved that subsequent chroniclers repeated his story and expanded his biography, a process that inadvertently extended his lifespan to 120 years.

Roland was not the only man to fart for money. In her book, Allen directs us to a medieval Japanese scroll that tells the story of a man named Fukutomi, who “performed fart dances for the aristocracy.” The story is the stuff of legend, but as Linda Rodriguez has written, there were professional farters at work in Japan by the 1700s. In Paris at the close of the nineteenth century, a baker’s son by the name of Joseph Pujol was able to host his own 90-minute show at the Moulin Rouge featuring renditions of “Au Clair de Lune.” Apparently Sigmund Freud visited the show before going on to develop his theory of “anal fixation.”

Across space and time, farting has been the source of embarrassment, especially to those of elevated social status. But the perils of holding in one’s farts were well known even before Dr. Oz told Oprah that people should break wind in public for health reasons. In his biography of the emperor Claudius, the Roman writer Suetonius records that Claudius “intended to publish an edict ‘allowing to all people the liberty of giving vent at table to any distension occasioned by flatulence,’ upon hearing of a person whose modesty, when under restraint, had nearly cost him his life.”

Strangely though, as Elizabeth Lopatto traced in her brief medical history of farting, the causes of “excessive flatulence” evaded medical science for millennia. As late as 1975, M.D. Levitt could remark, “there are no data available that prove excessive flatulence is actually caused by the presence of excessive intestinal gas.” It was only when Levitt conducted an experiment pumping the gas argon into patients via their rectum that he noted that people farted at the same rate that they were filled with gas. Astonishing. Curiously, it was not until 1998 that Levitt proposed a methodology for distinguishing between excess gas caused by swallowing too much air, and flatulence that resulted from processes that took place in the gut.

The difficulty regulating gas does have a silver lining. According to Jim Dawson, author of Who Cut the Cheese?, Adolf Hitler himself was a lifelong sufferer. Biographer John Toland credits Hitler’s flatulence to his vegetarianism, but others claim that Hitler turned to vegetarianism as a cure for his GI problems. Whatever the cause, by 1936, the cramps had grown unbearable. Early in his treatment Hitler ingested machine oil as a cure for gas, but around this time Berlin medic Theodor Morell prescribed Dr. Koester’s anti-gas pills, a concocotion that contained the poisons strychnine and atropene. According to Dawson, by 1941 Hitler was ingesting up to 150 pills a week. While not lethal, the side effects of these drugs include irritability, insomnia, and poor emotional health, a fact that came to light shortly before Hitler’s death when another physician decided to read the ingredient list for Dr. Koester’s little black pills. Dr. Morell was fired and, to many, seems lucky to have escaped with his life.

Whatever their cultural impact, farts continue to languish at the bottom of the socially acceptable hierarchy of bodily sounds. Burps might elicit some embarrassment, but hiccups tend only to amuse. Disease-spreading sneezes can be adorable, and even coughs are acceptable if covered by a sleeve or hand. But there has yet to be social rehabilitation for the lowly fart, even though scientists claim that the average person passes gas 14 times a day.